The Victorian Age. A complete historic article that explains how Great Britain in the 19th century became the wealthiest and most powerful nation in the world.

Just close your eyes – and think of England.

Queen Victoria

We will not have failure – only success and new learning.

Queen Victoria

Do not to let your feelings (very natural and usual ones) of momentary irritation and discomfort be seen by others don’t (as you so often did and do) let every little feeling be read in your face and seen in your manner.

Queen Victoria

Don’t forget to speak scornfully of the Victorian Age; there will be time for meekness when you try to better it. Very soon you will be Victorian or that sort of thing yourselves; next session probably, when the freshman come up.

J.M. Barrie

Ideas, like ghosts (according to the common notion of ghosts) must be spoken to a little before they will explain themselves.

Charles Dickens

There are three types of lies, lies, damn lies, and statistics.

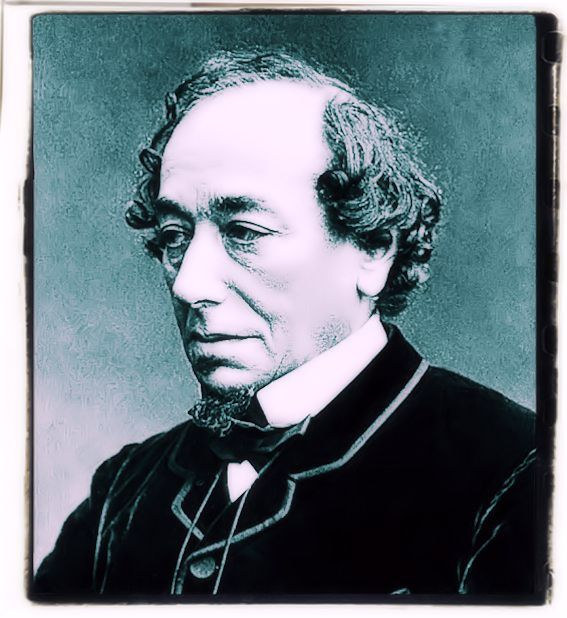

Benjamin Disraeli

When men are pure, laws are useless; when men are corrupt, laws are broken.

Benjamin Disraeli

Queen Victoria ruled Britain from 1837 to 1901. Her reign was the longest of any monarch in British history and came to be known as the Victorian era. As embodied by the monarchy, this era was represented by such 19th-century ideals as devotion to family life, public and private responsibility, and obedience to the law. Under Victoria, the British Empire expanded, and Britain became an increasingly powerful nation. As the country grew into an industrialized nation, the length and stability of Victoria’s reign gave an impression of continuity to what was actually a period of dynamic change. The death of Queen Victoria in January 1901 marked the end of an important era in British history. The queen’s personality and the stability of her reign contributed to her popularity. Family members present at her deathbed included her son, Edward VII, who followed her to the throne, and her grandson Emperor William of Germany. This account reflects some of the conventions and biases of the era in which it was written.

To understand better the Victorian period let’s have a quick look at what happened in Britain in the previous centuries. From 1660 until 1700 England experienced a commercial revolution. The navigation Act of 1660 had the effect of putting nearly all England’s trade, and that of her colonies, into the hands of English merchants. Trade increased dramatically, and ship building was in turn stimulated. England acquired a large empire in the seventeenth century. This brought her wealth and the need for a foreign policy geared to protecting and expanding colonial interests. England’s great commercial rival, Holland, was decisively beaten. In the next century England would defeat her great colonial rival, France.

In 1783 the Treaty of Versailles was signed by the Americans and the British; the Treaty acknowledged the independence of the United States. The loss of the American colonies was devastating. The colonies had a population exceeding 1,000,000, a highly developed economy and great towns. The British were still left with great possessions. There was Canada and India, the West Indies (which produced Britain’s sugar) and the trading posts on the west coast of Africa, which supplied the slaves for the West Indies and the American plantations. By 1779 Captain Cook had circumnavigated New Zealand, explored the east coast of Australia and chartered most of the principal groups of islands in the Pacific. In 1788 the first contingent of Britons, convicts and soldiers, landed at Sidney, Australia; the country was used as a dumping ground for prisoners into the nineteenth century.

Between 1809 and 1812 the British won a series of engagements against the French in Spain and between 1812 and 1814 Britain and the United States were at war with each other. In February 1815 Napoleon escaped from captivity on the island of Elba and returned to France. At Waterloo, near Brussels, in June 1815 the French army met Wellington, who was commander of the allied armies. Napoleon was defeated and permanently exiled to St Helena. The Congress of Vienna in 1815 drew up a map of Europe which was to remain largely unchanged until the last quarter of the century.

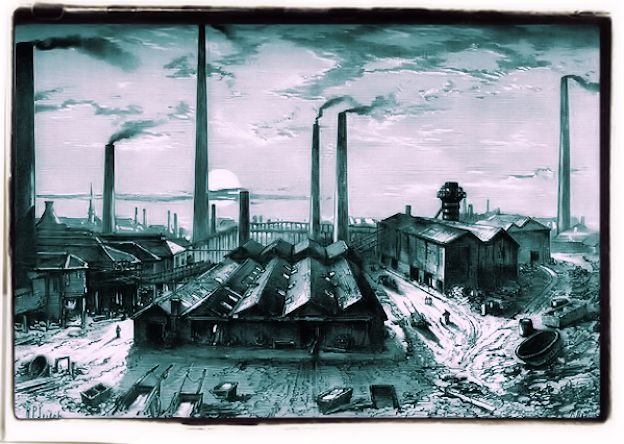

Britain had emerged as a very strong power in 1815. She had been sustained by her naval power and by the great industrial and agricultural achievements of the eighteen century, which had supplied the sinews of war. Internally the war had moved opinion to the right. The war (like all wars) created employment, but the inevitable recession following peace aggravated the tensions that lay beneath the surface of British life. Britain had a good base for industry. She had natural resources: wool, water, cola and some iron ore. Coal was a rapidly increasing source of energy after the eighteen century, and iron ore was vital to iron and steel production. In addition, England had the clays essential to the production of pottery. Other materials needed by industry, particularly cotton, could be imported.

As well as natural resources, Britain had other advantages. Britain’s climate meant there could be industrial production through the year. There were non insuperable geographical barriers to transport. there was unity and political stability. The stimuli to industrialisation were the greater commercial activity of the seventeenth century and a rapid rise in the population, which could be fed by increased food production. The wealth from trade increased investment and spending power in Britain. London was the greatest business and banking centre in the world by the end of the seventeenth century, and those with money were willing to invest it in improving land, sinking mines and building factories because profits were so high.

The population grew dramatically in the 18th century. In 1700 there were about 5,900,000 people in Britain and in 1801 about 9,250,000. There were more people to work in the economy and to buy goods. There were no large-scale wars and fewer mass epidemics. Hygiene was still elementary, but it was better; soap was a commodity and not a luxury. Buildings were better constructed and probably warmer. Yet by the end of the 18th century medicine had not improved much, and hospitals still tended to do as much harm as good. The enlarged population was fed, until the mid-nineteenth century, mostly with home-produced food. Farming steadily improved and there were vast improvements as well in transport. Textile manufacture was revolutionised by a series of inventions, the industry changed location when coal was used to produce steam power, but though James Watt patented a steam engine in 1782, its application to the textile industry remained experimental until the nineteenth century.

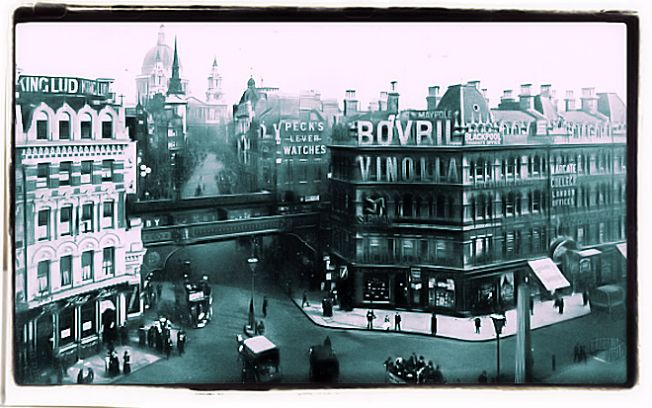

Specialisation of labour in industry advanced rapidly in the nineteenth century. Adam Smith, a Scottish academic, believed that freedom generated enterprise; therefore government should not interfere in industry or put restrictions in the way of trade between countries. This theory known as laissez-faire, was widely supported in the nineteenth century, particularly by the business community. By the middle of the eighteenth century London probably had a population of 700,000. The city was the political, financial and social capital and handled 80 per cent of the national trade.

A massive building programme in the 18th century resulted in the development of miles of Neo-Classical squares and terraces for the middle classes and the aristocracy; London had theatres, parks, churches and shops. In contrast, the poor in London lived in warrens of narrow streets. Crime was rife, but entertainment was plentiful. There were boxing matches without gloves, displays of fireworks and pageantry on state occasions, and even public hangings until 1783, which were considered social occasions. Crowds would feast the condemned on their way down Oxford Street to the gallows at Tyburn, where Marble Arch now stands.

Among the educated there was a growing love for Classical world. It was in the eighteenth century that the “Grand tour” became popular, when a young aristocrat, accompanied by a tutor, would visit the Classical sites of Italy and perhaps Greece. The taste for the Classical was reflected in the theme of the greatest history book The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire written by Edward Gibbon. He linked Rome decline with moral weakness as a result of its conversion to Christianity. Gibbon’s skepticism of religion was widely shared by 18th century intellectuals.

But Christianity had its supporters. The most impressive contribution came from John Wesley, who founded Methodism. This was a movement within the Church of England which emphazised method in one’s life. Wesley’s message was received warmily among the working class, particularly in industrial town. His Church later split from the Church of England to join the large number of Dissenting, Nonconformist or free Churches, among the Congregational Church, the Baptist Church and Wesley’s own Methodist Church.

Britain continued to industrilise rapidly in the nineteenth-century. By mid-century the population had risen to 18,000,000 (it had doubled since 1801), and less than a quarter of that population worked on the land. The first four decades of Queen Victoria’s long reign was a time of great national prosperity and confidence. By the middle of the 19th century, England had become “the workshop of the world”. The industry that reflected these changes most clearly was the cotton industry.

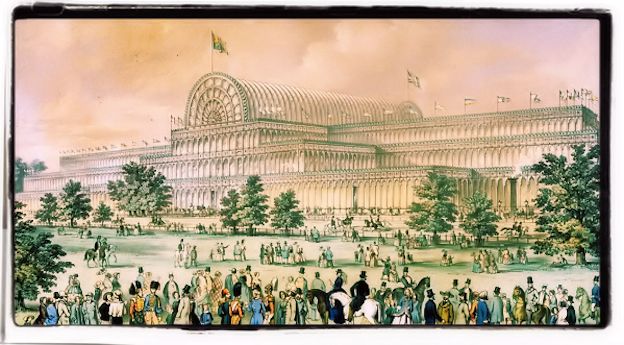

Equally impressive were advances in the coal and iron industries. The great boom in railroad construction came in the 1840s, by mid-century Britain had 8,000 kilometres of track. Her industries, railways and the vast increase in production was witnessed by the sumptuous International Exibition of 1851, held in London Hyde Park at The Crystal Palace built for the occasion, that set a model for the industrialization of other countries. Nevertheless Victorian society was far from idyllic.

Factory legislation was far from being sufficient and social evils such as child labour had not disappeared, class differences were marked as ever. In addition, Britain’s economic supremacy had started to be challenged by the increasing competitiveness of the American wheat prairies and the importation of refrigerated meat from Argentina. This gradually led to the near collapse of th3e economy and to the agricultural depression (1870-1902) which hit the landed aristocracy and the agricultural labourers particularly hard.

The emergence of a large industrial and urban working class and a rich and confident middle class was bound to cause tensions and change in the 19th century society. Economic distress among the working class produced sporadic violence. There were destruction of machinery by workers who felt their jobs were threatened, they were called Luddites. There were also destruction of farm property by hungry farm workers in the countryside.

There were also the rise of mass-working class movements. Unions were organized, and in 1840 the was the rise of Chartism, a movement which demanded political rights for workers, but these organizations failed after a short period of time through lack of funds. Anyway the Authorities were nervous, fearful that radicalism got out of hand, and they feared that a revolutionary order would be established, as in France.

The passing of the Reform Bill in 1832 had extended the right to vote to much of the male middle class. As the right to vote was based on property, many working class people were bitterly disappointed because they were excluded. Therefore the period from 1832 to 1848 was characterized by dissatisfaction and unrest in the lower classes. In effect, this act gave the middle class the vote and included the Midlands and the north in the political nation. The passing of the Reform Act helped Britain to acquire political maturity peacefully and spared the middle class the need to use force to gain constitutional change, that’s why this was the first step on the road to democracy, though the number of new voters was relatively small.

A Factory Act passed in 1833 imposed limits on the hours worked by children. The importance of the Act was not its modest achievement but the fact that it established the principle of government intervention in industry to promote health, safety and humanity. In 1842 a Mines Act forbade the employment underground of women and boys under ten. Most important, an inspectorate was created to supervise the implementation of the Act. The Poor Law Act of 1834, which provided bare subsistence in parish workhouses for those out of work, was not popular. Going to the workhouse became a mark of shame. Men and women had to go to separate houses , and families inevitably split up. By 1850 there had been further reforms in the working conditions of women and children in factories, and by mid-century many factories had, for the first time, introduced a Saturday half-day for their work force.

Town government in England, Wales and Scotland was overhauled in 1835, with the creation of new boroughs governed by municipal councils which were elected by local taxpayers. In 1846 a General Board of Health was set up, following the production in 1842 of a momentous report by Edwin Chadwick: “The Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Classes”. Local councils were left to set up their own local boards. This was a major step forward in the promotion of healthy living standards nationally but particularly in the cities. In 1833 money was given to two religious societies, Anglican and Nonconformist, to promote education. What is surprising is that England was so slow to take a serious interest in providing state education, and compulsory education did not arrive until 1870. England compares badly with Scotland and some Continental countries. Another important reform of the century was the abolition of slavery in 1833. It took some time to put the measure into effect, the abolition movement was essentially evangelical (extreme Protestant), and testified to Christianity’s repugnance of slavery.

During the Victorian Age, Britain’s modern political parties were born: the Conservatives grew out of the old Tories and the Liberals out of the Whigs. From the ’60s to the ’80s the tensions in British society and politics were embodied by the rivalry between the leader of the Liberal Party, William Ewart Gladstone (1868-1874), and the head of the Conservative Party, Benjamin Disraeli (1374-1880). Gladstone, four times Prime Minister after 1868, was earnestly in favour of political reform. In his first ministry the great statesman tried to find reasonable solutions to the chronic “Irish question” by the Act for the Disestablishment of the Irish Church (1869 and especially by the Irish Land Act (1870). The former sanctioned the equality of all religious denominations in the island; the latter aimed at facilitating the creation of a system of peasant proprietorship so as to prevent a dangerous agrarian agitation. After dealing with Ireland, Gladstone introduced through Parliament important measures concerning Great Britain.

The 1870 Elementary Education Act recognized the need for generalized primary schooling, which was made compulsory in 1880. Some of the most important legislation of the century was passed during the following years: in 1871 the Trade Unions were formally recognized; in 1872, the Ballot Act secured the secrecy of vote at elections; in 1873, the Judicature Act simplified legal procedures. In his second ministry, Gladstone passed the Third Reform Bill of 1884 which granted suffrage to agricultural labourers and miners. While Gladstone was strong on domestic policy and reform, he was perceived as weaker in foreign policy. Disraeli was strong precisely where Gladstone was weak; when the latter lost the 1885 election, he did so because Disraeli had succeeded in implanting the idea that imperial power was a measure of national greatness. He was a strong supporter of Britain’s imperial role and during his ministry pursued a foreign policy of expansion in the Near East, forming an alliance with Turkey to defend British interest against the Russian challenge. In 1906, a new political party was founded: the Labour Party.

Britain only went to war twice in this age, in the Crimea (1854-1856) and in South Africa (1899). The ostensible reason of the Crimean War was to protect Turkey from Russian invasion, but the underlying purpose was to contain Russian expansionism over the Dardanelles, which was threatening England’s supremacy over the Mediterranean, an area of great sensitivity for Britain, with its preferential routes towards its imperial possessions in India and Burma. At the outbreak of the war, Alfred Tennyson voiced the ideals of his age in the poem The Charge of the Light Brigade (1855) where he praised the soldiers’ heroism and justified their unquestioning acceptance of death: “Theirs not to reason why, Theirs but to do and die.” Although Britain won the war, the expedition was not a success. Lives were lost needlessly due to the incompetence of the high command. Moreover, the Paris Treaty (1856) gave way to a long period of tension and hostility between Russia, England and France.

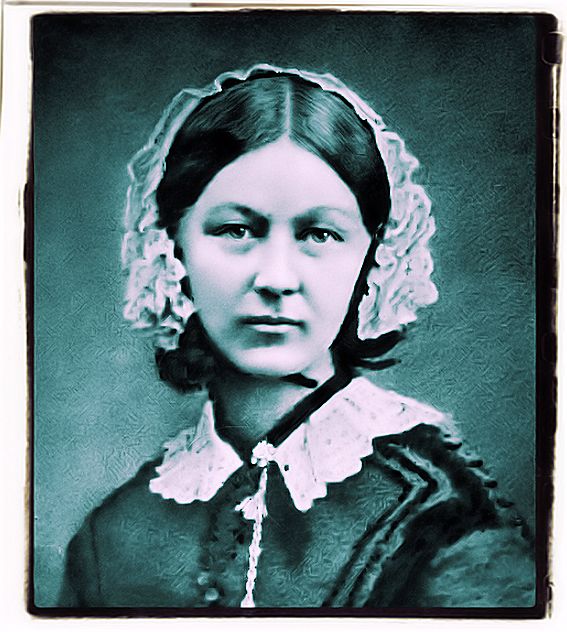

The real heroine of the Crimean War was Florence Nightingale (1820-1910). She was named Florence, after the Italian city where she was born to wealthy British parents. She went to study in a hospital in Paris, and at 33 she became superintendent of a women’s hospital in London. When Great Britain and France went to war with Russia in the Crimea, in 1854, she was asked to take charge of Nursing. She sailed for the Crimea with 38 nurses. She introduced sanitary methods of nursing into the old, dirty and unfurnished Turkish hospital. She attended to the nursing needs of British soldiers; at night her lamp, burned as she walked the four miles of corridors and wrote countless letters demanding supplies from British military officials. It Was the first time that soldiers wounded while fighting away from home received good hospital care. Modern nursing, both military and civil, can be said to have begun with her and she was also responsible for spreading a new conception of the potential of the trained and educated woman in society.

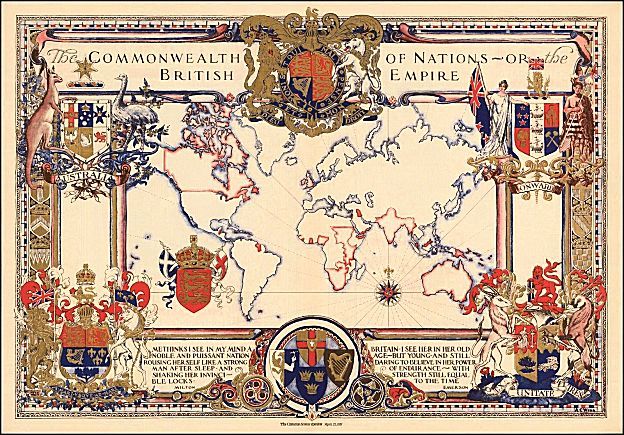

By the mid-1800s, British trade was firmly established in India. Trade was also strong in the West Indies, where fertile soil was used to grow sugar and other important crops. In Canada, Britain controlled extensive colonial territories. On the other side of the world, Australia served as a remote prison for British criminals, as the North American colonies had decades earlier. Bartholomew’s map also reflects the recent acquisition of Hong Kong, which followed the First Opium War (1839-1843). Many of the smaller red-bordered territories represent trading posts and missionary encampments. The British presence in India began with the English East India Company’s founding of a trading post at Surat in 1612. By the early 1800s, most of India was under the control of the East India Company, and in 1858 the British Crown took over administration of India. Here, members of a British family in India pose with their servants.

The first British Empire was the creation of explorers and traders and was based on an economic relationship between colonies and the mother country. The second British Empire was the creation of bureaucrats and generals and was based on a political relationship known as imperialism. Imperialism involved an effort to rule native peoples by importing British institutions and values, intervening in local affairs, and maintaining a strong military presence. The shift in goals and methods was gradual. The most important colonies of the first empire had developed in sparsely populated regions where native populations were brutally cast aside to establish British colonies. The second empire involved the domination of colonial peoples.

British naval power enabled Britain to control a far-flung empire, especially after the development of steam-powered warships. Geographical emphasis shifted from the west to the east; the most important dominions were located in the South Pacific, South Asia, and Africa. India was the centerpiece of the British Empire. British rule in India began with the expulsion of the French from Bengal in 1757 and grew as the British used military conquest to gain direct control over areas of India. Wars in Afghanistan and the Punjab in the 1840s led to British annexation of the northern Muslim provinces. The British created a unified India out of hundreds of separate kingdoms and principalities. The conquest of the eastern territory of Burma (now Myanmar) began in the 1820s and ended following the second Anglo-Burmese War in 1852.

Successive governors-general attempted to bring to the Indian subcontinent what they regarded as Britain’s superior system of law and social relations. They governed through a vast civil service transplanted mainly from Britain. Although the British made significant inroads against the extremes of poverty and disease that existed in India, they generally viewed Indian society as less cultured than their own and treated the indigenous population with contempt. Inevitably a clash of cultures took place. In 1857 there was a mutiny by sepoys (Indian troops in the British military), who sought to protect their social and religious traditions. The sepoys seized garrisons and killed British officers and civilians. British relief forces repeated the process in reverse, and the Sepoy Rebellion left a legacy of mutual hostility.

British expansion into Africa was fueled by the race for colonies in which all of the European powers participated during the decades that followed the 1880s. British traders had long been present on the western coast of Africa, where they dominated the Atlantic slave trade. With the abolition of slavery after 1833, interest in Africa shifted to the east, where the British drove the French from Egypt. In 1882 the British gained control of the Suez Canal, a vital link between Britain’s eastern and western empires.

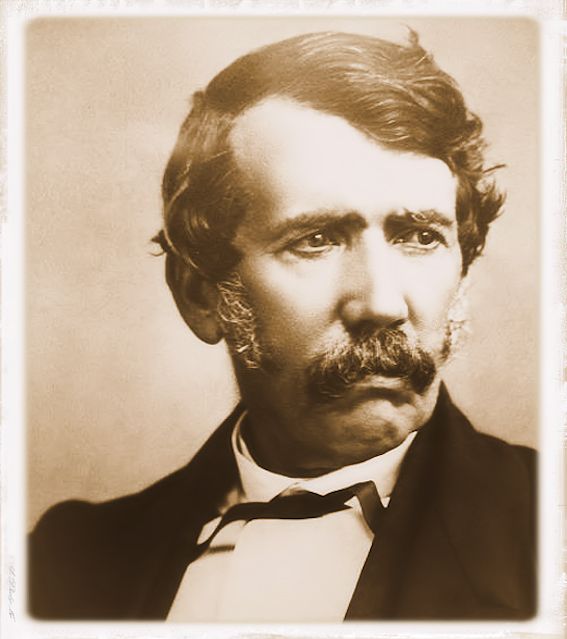

Dr. David Livingstone was one of the greatest explorers of the African continent, along the way pioneering the abolition of the slave trade. When no one had heard from him for several years while he was exploring the interior of the continent in the 1860s, his long absence became a matter of international concern, and the New York Herald sent explorer Henry M. Stanley to find him in 1869. Stanley finally found Livingstone in November 1871 in a small town on Lake Tanganyika. He greeted Livingstone with the famous words, “Dr. Livingstone, I presume.”

British explorers such as David Livingstone helped open the interior of Africa to Europeans, while entrepreneurs such as Cecil Rhodes exploited its vast mineral wealth. Rhodes acquired one of the great fortunes of the second empire by gaining control of African diamonds and gold. He dreamed of unifying the eastern side of the continent by establishing a railroad from Cape Town in the south to Cairo in the north, passing only through British controlled territory. Rhodes’s efforts helped trigger the Boer War (1899-1902), in which British troops fought Dutch colonists for possession of some of the richest gold and diamond mining areas of southern Africa. The Scramble for Africa created conflicts between the European powers, and Rhodes’s scheme faltered because of the powerful German presence in eastern Africa.

Cecil Rhodes used his great wealth, made from mining diamonds in Africa, to extend British rule in southern Africa. Upon his death in 1902, much of Rhodes’s vast fortune went to the University of Oxford for the establishment of Rhodes scholarships. Seeking to expand the opportunity for trade along the Chinese coast, the British acquired the island of Hong Kong in southern China following the first Opium War (1839-1842) with China. The war broke out when Chinese officials in the port of Guangzhou seized the opium shipments that merchants were illegally importing into China. The British responded by sending a naval force and occupying Hong Kong in 1841.

Increasing numbers of Britain’s growing population began to look for a future elsewhere. Some chose the US, others emigrated to Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. These colonies known “the colonies of settlement”, witnessed mass immigration by Englishmen, who claimed large areas of the land and pushed the native people out. In some colonies home rule was eventually granted, giving them dominion status. In Canada, jealousies and suspicions between the two provinces Upper Canada (Ontario – anglophone) and Lower Canada (Quebec – francophone) led to revolts in both of them in 1837. With the intervention of the British government rebellion was suppressed and the two provinces were united in 1840. The British North America Act of 1867 made Canada the first self-governing dominion within the British Empire.

In Australia, between 1849 and 1851, gold was found in Victoria and New South Wales. This attracted thousands of new immigrants. Few succeeded as gold prospectors, but many stayed as settlers. The British annexed New Zealand in 1840. Maori people accepted British rule in the Treaty of Waitangi. But disputes between Maoris and settlers resulted in war in 1860. The Maoris lost, but kept their lands and legal rights. They shared with British settlers in New Zealand’s development. There too, the discovery of gold, in1861, brought an increase in population. New Zealand prospered as a farming country and became a dominion in 1907. In 1876 the Conservative Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli introduced the Royal Titles Bill, which made Queen Victoria the Empress of India and by 1900 the small island of Britain governed one fifth of the world territories.

To find out more about this period you can also read: