The teachings of Plato, originality of his works, myths, methods, ideas, forms, thoughts, education, ethics, morals and art of his great everlasting philosophy.

To do philosophy correctly consists in not choosing the worst types of existence over the best by ignorance of the best and the worst, and, when the best have been chosen, in not leaning toward the worst by an uncontrolled impulse.

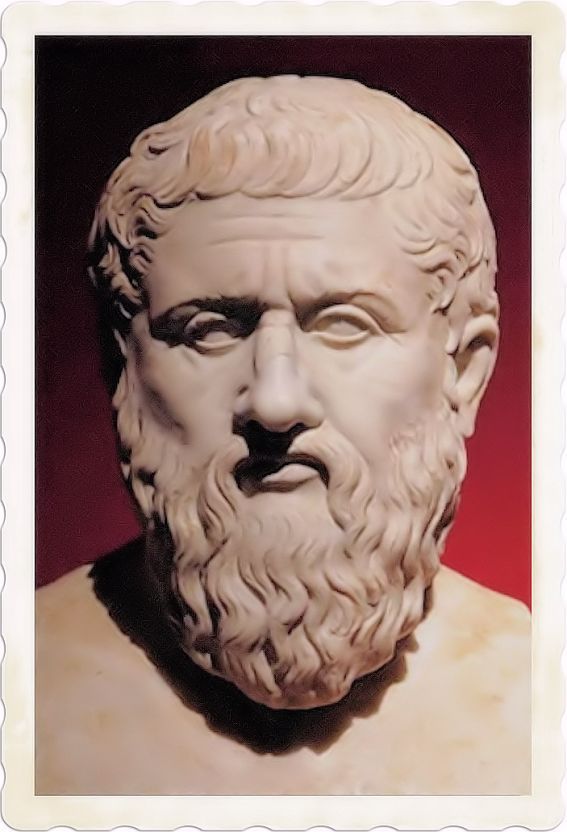

Plato

Those who are able to see beyond the shadows and lies of their culture will never be understood, let alone believed, by the masses.

Plato

As long as they are shoemakers who are incapable or corrupt, or who boast of being skilled even though they are not, it would not be a great loss for the state. But you see well that if the Guardians of the laws and of the State were to pretend to be guardians, when they are not, it would be the whole City that would run the risk of complete destruction, precisely because its happiness and its good administration are in their hands.

Plato, The Republic, IV, 421A

Questioning oneself is the task of the philosopher, because there is no other way to initiate philosophy.

Plato

Human behavior always springs from three main sources: desire, emotion, and knowledge.

Plato

Everything in this world is a shadow of its ideal form in the world of ideas.

Plato

The details necessarily and inevitably lead back to universal.

Plato

The soul of man is immortal and imperishable.

Plato

Learning is remembering.

Plato

Beauty is mixing in the right proportions the finite and the infinite.

Plato

The best solution to all problems is patience.

Plato

By nature, opinion likes to opine.

Plato

Men condemn injustices not because they consider it criminal to commit them, but because they fear that they may be victims of them.

Plato

For the good of states it would be necessary for philosophers to be kings or kings to be philosophers.

Plato

Slaves and masters can never be friends.

Plato

Socrates: “What will Eros be then?” Diotima: “A great demon, O Socrates: for all that is demonic is something between god and mortal.”

Plato

Keep in mind that great wealth and extreme poverty make man unhappy because one produces luxury, laziness and revolutionary movements, and the other narrowness, poor work and revolutionary movements.

Plato

One should not honor a man more than the truth of stupidity.

Carl William Brown

Already more than 2000 years ago Plato advised to have politics administered by philosopher-kings who could not own private property; now after centuries of cultural progress we find ourselves in the power of super-ignorant imbeciles who think only of ripping off money, of course with the consent of the civilized people.

Carl William Brown

If our humanity has gone from the greatness of philosophers such as Socrates, Plato and Aristotle to the imbecility, selfishness and deleterious profiteering of so many of our modern politicians and intellectuals, it means that our educational, pedagogical, communicative, judicial and administrative system has failed miserably, as have religions and the greatest exponents of all current philosophical currents, artistic and literary. The only authority that has truly triumphed over the centuries is the stupidity of our societies. The responsibility obviously lies with all of us, but it is mainly to be attributed to our leaders, who are such, precisely by virtue of the painful mental condition of those who consider them as such.

Carl William Brown

I have in fact the firm conviction that, as Reinach affirms, Plato is the “greatest philosopher ever” to appear on earth, and that the task of those who want to understand him and make others understand, while getting closer and closer to the Truth, can never end.

Giovanni Reale, Plato. In search of secret wisdom.

The great intuition of Plato, still difficult to refute today, was precisely that of conceiving the world of ideas, perfect and complete in itself, unlike that of matter, which is deficiency, imperfection, banality, stupidity, fallacy, error and pain, which moreover degrades more and more compared to the perfection of ideal models and therefore produces effects, especially on humans, which get irreparably worse over time. Had he thought only this, he would already have been the greatest philosopher of all time.

Carl William Brown

Socrates said that the task of man is the care of the soul: psychotherapy, we could say. That today the soul is interpreted in another sense, this is relatively important. Socrates, for example, did not pronounce on the immortality of the soul, because he did not yet have the elements to do so, elements that only with Plato will emerge. But, despite more than two thousand years, it is still thought that the essence of man is psyché. Many, mistakenly, believe that the concept of soul is a Christian creation: it is very wrong. In some respects the concept of soul and immortality of the soul is contrary to Christian doctrine, which speaks instead of the resurrection of the body. That the first thinkers of the Patristics used Greek philosophical categories, and that therefore the conceptual apparatus of Christianity is partly Hellenizing, should not make us forget that the concept of psyché is a grandiose creation of the Greeks. The West comes from here.

Giovanni Reale, History of ancient philosophy.

Beyond the opinions that everyone can make on Plato’s thought, however, it is undeniable that this author is the first great philosopher who does not focus only on the explanation of the external world and the cosmos, but expands his research to those that will become the main issues of this discipline: ontology, epistemology, aesthetics, political and moral philosophy, and in doing so it explicitly formulates or anticipates the essential categories of philosophical thinking. To confirm this, it is enough to think that the English philosopher Alfred North Whitehead has come to affirm that “the most certain way to define the European philosophical tradition as a whole is to say that it consists of a series of notes in the margins of Plato.” Moreover, even the anti-Platonist Michel Onfray recently argued that: “the way of writing the history of philosophy is platonic. Broadening the picture: the historiography of the liberal West is platonic.” So for better or for worse it is obvious that one cannot understand the history of thought without knowing Plato.

E.A. From the Male

The doctrine of ideas according to which objects of scientific knowledge are entities and values that have a status different from that of natural things and characterized by unity and immutability. According to this doctrine, sensible knowledge, which has as its object things in their multiplicity and changeability, does not have the slightest truth value and can only hinder the acquisition of authentic knowledge.

The doctrine of the superiority of wisdom over wisdom, that is, of the political end of philosophy: which has as its final goal the realization of justice in relations between men and therefore in every single man.

The doctrine of dialectics as a scientific procedure par excellence, that is, as a method through which associated research in the first place comes to recognize a single idea and in the second place goes on to divide the single idea into its specific articulations.

Nicola Abbagnano placeholder image

Plato uses both the terms “forms” and “ideas” indistinctly, indeed he privileges the second over the first. However, it is of fundamental importance to emphasize that when Plato speaks of “ideas” he is not referring to a creation of our mind, to the result of a mental process (that is, to what we refer to today with the term idea). Platonic ideas are not abstractions or constructs of the thinking subject, a product of the I, the Ego or the transcendent subject who thinks, but real entities, existing regardless of whether there is a subject who thinks or sees them: they are “things”. In this sense, the term “form” is clearer and less likely to be confusing.

E.A. From the Male

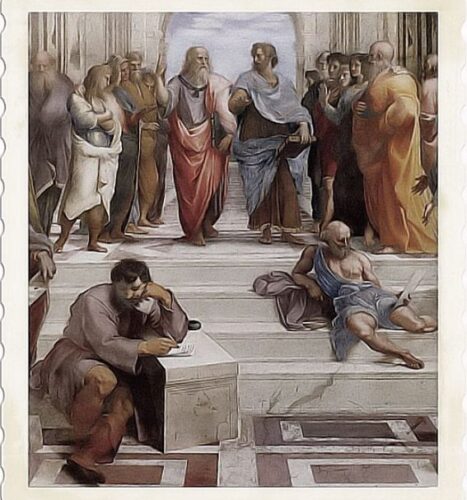

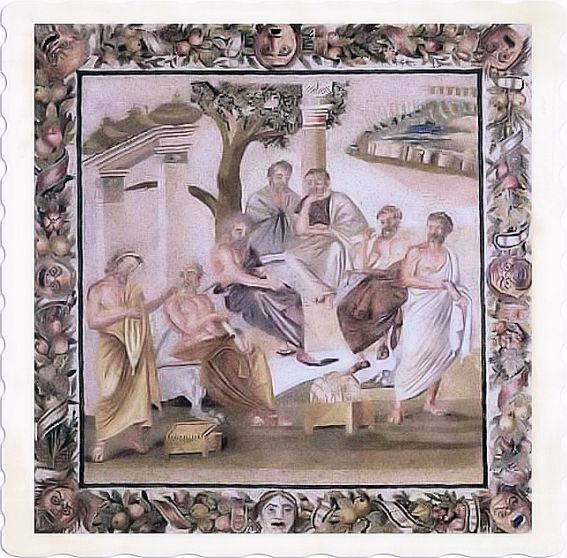

Plato (Athens 428 – 347 BC), was born into an aristocratic family that counted among its ancestors the legendary king of Athens Codro and the legislator of the sixth century BC Solon. Widowed, her mother married Pirilampus, an aristocratic friend of Pericles who raised Plato in a democratic cultural environment. The young man enjoyed a thorough artistic education (he studied painting, music and composed lyrics and dramas), receiving rudiments of philosophical education from Cratylus, a follower of the doctrines of Heraclitus; However, the knowledge of Socrates was decisive, of which he became a pupil.

Plato witnessed with him the fall of the rule of the Thirty Tyrants and the restoration; after the death of Socrates, decreed in 399 BC by the democratic government, embittered by the political situation and accused of aristocratic sympathies, he left Athens and traveled to Egypt and Magna Graecia. In Taranto he met Archytas, a follower of the doctrines of Pythagoras, and in Sicily, in Syracuse, the tyrant Dionysius the Elder. He, annoyed by Plato’s attempt to put his political conceptions into practice by exerting a beneficial influence on his young brother-in-law Dione, arrested him and put him up for sale as a slave in Aegina. Redeemed, fortunately, he returned to Athens, where in 387 BC he founded a philosophical school, which from the name of a mythical hero was called Academy.

Further trying to merge his philosophical conceptions with political practice, Plato went to Sicily in 366 BC, always invited by Dio, with the aim of educating the successor of Dionysius the Elder, Dionysius the Younger, to good government. Dionysius, however, instigated by a powerful faction of opponents, exiled Dione. In 365 BC, because a war had broken out in Sicily between the Greek cities, Plato embarked for Athens; he returned to Syracuse in 361 BC, but once again the journey proved fruitless – the measures taken by Dionysius against Dio became more and more serious – and, accused of conspiracy, he could return to Athens only thanks to the intercession of Archytas of Taranto. From then on he was involved in teaching at the Academy until his death, which caught him an octogenarian.

Plato is the thinker who, thanks to the breadth of the themes dealt with and the questions posed in his works, delimits for the first time all or almost all the areas that define the task of philosophy and therefore results in one of the greatest founders. His dogmatic attachment to the negation of the senses and the imprudent extension of the concept of reality (form) to any term or object of our thought certainly make him fall into contradictions, errors and mythical and surreal interpretations, however his success is due to the fact of transcending reality and aspiring to a higher ideality, through continuous research and constant philosophical commitment, and therefore pragmatic, in the pursuit of good, beauty and justice, through a wise control of the most negative passions. Happiness for Plato consists in the search for the Good and the Beautiful: but once these goals have been achieved, through an education that leads to wisdom, understood as the ability to distinguish the true good and the true beautiful from false goods, and once the desire for happiness is satisfied, this vanishes if another desire does not arise.

Individual morality then is not sufficient for the attainment of happiness that must instead be guaranteed by the State led by philosophers who alone are able to create the favorable conditions for the happiness of citizens. His philosophy, precisely because of its spirituality, is not only very similar to Christianity but we can say that it lays its foundations. The immortality of the soul, an eschatological doctrine that provides for rewards and punishments after death, contempt for the body and pleasure, the reality that is of another world, a political ideal centered on a society ruled by a caste of wise men possessing the truth that rules over a flock whose mission is to obey, they are a very fertile ground in which it was enough just to plant a Creator God and eliminate some unwelcome things, such as homosexuality, reincarnation, to obtain precisely the new Christian doctrine on which to start working.

Again to connect us to a creator God, the story of the creation of the universe and of man by the Demiurge in Plato is mythical, yet in many points it is nothing more than a further development of the theory of ideas. The Creator of the world does not create things from nothing; He shapes the world from a pre-existing chaos of matter by introducing models taken from the sphere of forms. This process of formation is also explained in the Timaeus in terms of various mathematical figures. In the first period of the universe God (Chronos) exercised a kind of providential care on the things of this world, but in the end man was left to his will. The story, at the end of the Republic, describes a judgment of souls after death, their separation between good and bad, and the awarding of various punishments and prizes.

It should also be considered that Plato’s conceptions were interpreted religiously by Plotinus who founded the Neoplatonic school in 250 AD and later in 386 St. Augustine of Hippo integrates Plato’s theories into Christian doctrine. Thus Platonism was always held in high esteem by the Fathers of the Church such as Ambrose, Augustine, John Damascene and Anselm of Canterbury and continued to be the philosophy approved by the Church until the twelfth century. But not only that, Humanism and the Renaissance marked a revival of Platonism in the Florentine Academy of Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola. Later in England the Cambridge Platonists (H. More, Th. Gale, J. Norris) in the seventeenth century marked the beginning of an interest in Plato, which has not yet died out in English universities. Today the ethical writings of A.E. Taylor, the theory of essences carried out by G. Santayana and the metaphysics of A.N. Whitehead are forms very close to a contemporary Platonism.

Although Platonism is characterized by a partial contempt for knowledge of the senses and experimental studies, it nevertheless has a high regard for mathematics and its method. There is in Plato a strong aspiration for a different and better world (ideal therefore), his vision is clearly spiritualistic, and his method of discussion implies an ever deeper intuition, rather than a logical path followed for example by Aristotle, and above all there is in him a firm faith in the ability of the human mind to reach absolute truth and to use this virtue to rationally direct life and works. Human. The forms for Plato are “discovered” through memory and are “contemplated” and during this process the eye of the soul is brought out. It is something that resembles an illumination, that is, an almost mystical access to truth. In this he reminds us of the role of the poet in the oral tradition, which does not have the function of creating or knowing on its own, but that of remembering: of composing, therefore, under dictation, to receive a widespread and impersonal wisdom.

It is no coincidence that the inspiring divinities of the poets are the Muses, daughters of Apollo and Mnemosyne, goddess of memory. His theory of education is therefore based on the extraction (educatio) of what is already confusedly known by the learner, a sort of innatism of universals such as linguistic, but not only, to be clear. Of course the educational program of the philosopher-kings was a bit excessive, it had to last until the age of thirty-five, studying literature, philosophy, gymnastics, mathematics, dialectics, then another fifteen years of practical apprenticeship were required in the subordinate offices of the state, and finally at fifty the rulers were advised to return to the study of philosophy.

Plato through the myths constricts his philosophical and conceptual interpretation of reality. For example, in the Phaedrus, we discover that before birth, immortal souls wander in the heavens around those of the gods; During the flight they cross the celestial region where the forms reside and can contemplate them fleetingly in a vision that they will forget the moment they join a body at birth. But it is precisely this vision of forms before coming into the world that allows us to discover them once we have become ordinary mortals, in fact the relationship with the different objects of our experience, which are all copies of forms, awakens in this way in our soul the memory of the essences contemplated before birth.

This in practice is Plato’s theory of knowledge, it is the doctrine of anamnesis, of reminiscence. We find the confirmation of all this in what follows: throughout our life we see infinite objects more or less equal to each other, and from them we arrive at the idea of equality, however since equality in itself is not something that belongs to the world of our experience (there is no object “equality”), this idea cannot come from the senses and must somehow be present in our soul already before birth. To know, to rise to the point of form, is to remember: “For the soul that has never seen the truth will never reach this human form of ours. Because man must understand what is called Idea, passing from a multiplicity of sensations to an organized unity of reasoning. This understanding is reminiscent of the truths that the soul once saw, when it flew in the wake of a God.” Plato Phaedrus 249 b-c

On the biographical level, Plato, writing his dialogues, literally brings Socrates back from the kingdom of the dead, to make him continue to discuss with us and this is the greatness of Plato’s dialectical method, extended not only to the living, but also to the great of the past and to the kingdom of the dead, thanks to memory, which is the basis of learning; later T.S. Eliot would say “And what the dead had no speech for, when living, They can tell you, being dead: the communication Of the dead is tongued with fire beyond the language of the living.” From a literary point of view, a written dialogue, if it manages to stimulate the reader’s first-person thought, is metaphorically a return from the realm of the dead.

Thanks to Plato we realize that ideas born in a temporally and spatially delimited context can come back alive in the relationship with the reader, and even say something new and creative. In this way they have, in addition to the first, infinite subsequent lives. Without Plato we would hardly even know the thought of Socrates, who is still alive and talking to us, or, better, reading the Platonic texts, infinite Socrates are revived, in connection with what we think on our own. From the moral point of view, a free choice can be thought of as a death, that is, as a break with the past. At the same time, however, it is also a return to life, if you know how to remember how and why you chose.

Plato also taught us that only neglect makes us forget that we, having chosen, are free, and that we can make ourselves better. Our freedom is “mythical” in the sense that we can only be aware of it by critically remembering our history – as poets could not, who are condemned to repetition and uncritical immersion in a non-conceptual, irrepressible and indefinable flow, just like the water of the Amelete river. If our choices are important, and if we know how to keep it in mind, it will be clear to us that the world can be better than it is.

We are in the world of Ananke, but change is possible, because we ourselves can transform and improve ourselves. Er’s return from the realm of the dead is a strong image of the spirit that inspires Plato’s metaphysics: reality exists only to the extent that it is alive and striving for the better. We exist fully only if we know how to make our choices – if we know, that is, valiantly die and consciously be reborn, without forgetting anything, as in the extraordinary story that puts an end to the Republic.

The Platonic philosophy of art emphasizes the value of rational imitation of ideal realities, rather than photographic imitation of sensual things and individual experiences. All beautiful things participate in the idea of beauty. The artist is often described as a man carried away by inspiration, similar to a madman. Beautiful art is not distinguished from useful art, so much so that both in the Republic and in the Laws art is subordinated to the good of the state, and asocial forms of art, dangerous to the morality of citizens, are severely excluded. Plato’s ethics are intellectualistic, and wisdom is the greatest virtue. Fortitude and temperance are the necessary virtues of the lower parts of the soul, and justice, in the individual as in the state, is the harmonious cooperation of all parties under the control of reason. Of the pleasures the best are those of the intellect, and the greatest happiness for man is found in the contemplation of supreme ideas.

In Platonic theory, love (eros) is ignited in contact with physical beauty but, sensing in it the presence of the idea, ascends, gradually, to it, resolving itself in the noetic contemplation of absolute Beauty, in which it is aqued. From the story of the dialogue between Socrates and Diotima in the Convivio (or Symposium) we arrive at the definition of love as “desire to always possess the good” or more precisely, “the love of generation and procreation in beauty” because for Plato the Good in itself and Beauty are the same thing. “Because this is precisely the right way to advance or to be guided by others in matters of love: beginning with the beauties of this world, in view of that last beauty always climbing, as if by steps … to the point of being able to contemplate the same divine beauty, pure simple, not mixed, nor clothed with human flesh, nor with colors, nor with any other mortal frivolity, in the uniqueness of its form”. Therefore, all men share the universal desire for goodness and beauty, a desire which, appropriately channeled into those who are “fruitful in the soul”, causes their spirit to rise above material reality to discover the forms of Beauty in itself. Socrates: ” What will Eros be then? ” Diotima: “A great demon, O Socrates: for all that is demonic is something between god and mortal.

A fundamental idea, inherent in the name itself, that Plato helped to spread is that of the Daimon. “Daimonia kaina” literally means “new divine (creatures)”. The daimonion spoken of in the Apology is the neutral adjective that comes from daimon (from daiomai: pantry, do in lote), a divine creature not necessarily malevolent, who presides over the fate of men, a kind of tutelary genius, a spirit that advises and directs us, and that stimulates us to reflect, without imposing its decisions on us. A daimon is contained in the word eudaimonia (happiness), which means, etymologically, something like: “a good daimon rules my destiny”. The daimon is the divine creature who presides over the destiny of each one. In Er’s story, the daimon does not happen to be a lot, but is the object of a choice. Freedom of choice makes virtue “without a master”, unlike what happened in traditional morality, where this was the prerogative of a well-determined social figure, the aristos, or in any case of an extremely small group.

Choice, and therefore freedom, is something independent of our bodily and social image: paradigms of life of all kinds, of men, women and even animals, are offered to the choice. However, in Platonic philosophy it is the souls who choose their fate, and precisely for this reason they can make very different choices: each one procures happiness, in the modern sense of personal satisfaction, in his own way. But Socrates emphasizes that the question of choosing, and choosing rightly, so as to maximize eudaimonia, is a capital problem. This eudaimonia exists not so much because a good daimon presides over our destiny, but because we ourselves have chosen a good daimon. An essential element of eudaimonia, therefore, is no longer the daimon, but the character of our choice. There can be no eudaimonia without autonomy. If choosing is essential, happiness cannot be reduced to a model, according to which to cultivate people. Also for this reason, the paradigms of life offered as an option are numerous and different from each other.

With the great merits of Plato who assigns to philosophy, dialectics, the constant commitment of the thinker, the extreme value of good behavior to pursue good and wisdom, a fundamental importance, there are however also some defects in his conceptual and methodological approach: the first is certainly the devaluation of the role of the senses in cognitive investigation that has opened a profound detachment of technical and empirical culture that will be filled only in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. century; then we have the attribution of an extremely mystical and almost magical character to numbers, a defect that dates back to Pythagoras, and this will entail over the centuries serious consequences in the field of the non-application of mathematics in the epiric world; finally we can say that the very greatness of Plato’s influence in the history of thought, gave the culture of the time and also to the subsequent one such a profound imprint as to determine also a limit and a difficulty for further innovations and research in the field of scientific and experimental knowledge.

In conclusion, we can in any case say that Plato, the ancient Greek philosopher, a pupil of Socrates and teacher of Aristotle, undoubtedly laid the philosophical foundations of Western culture. Based on the life and thought of Socrates, he developed a very original and profound philosophical system. His thought has logical, epistemological and metaphysical aspects, but his underlying motivation is ethical and more relevant than ever. Sometimes it is based on conjecture and myths, and occasionally has a mystical tone. However, Plato is a rationalist, devoted to the proposition that reason must be followed wherever it leads and this clearly opens the way to Aristotle’s new research that integrates philosophy with the fundamental role of logical observation of the reality that surrounds us. So we can say that the core of Platonic philosophy is a rationalist ethics of all respect from which we can not distance ourselves nor can we help but deepen it and study it also in the future.

For those wishing to learn more about the topic, I suggest the following articles, for the moment mostly in Italian, but soon they will be also translated into English.

Principles of Daimonology (from n. 1 to n. 50)

Principi sintetici di Daimonologia