The power of English, the diffusion around the world of the English American language during the past centuries and the technological contemporary epoch.

Adaptability is not imitation. It means power of resistance and assimilation.

Mahatma Gandhi

English language is the most universal language in history, way more than the Latin of Julius Caesar. It’s the most powerful language because its vocabulary has a certain critical mass that makes a lingo good for punning.

Richard Lederer

Nowadays a world language is more important for mankind than any other progress in television, telephony or Internet.

Carl William Brown

English today is probably the third largest language by number of native speakers, after Mandarin Chinese and Spanish.

Carl William Brown

Viewed freely, the English language is the accretion and growth of every dialect, race, and range of time, and is both the free and compacted composition of all.

Walt Whitman

We all live in a small unique world, that’s why we need at least one sole common language.

Carl william Brown

At the time of Elizabeth I (1533-1603), there were at most seven million native speakers of English and there were very few non-native speakers of it. Dutch was seen as a more useful language to learn than English. Yet by the time of Elizabeth II (1926– ) the number of native speakers of English had increased to some 350 million. If we add non-native speakers to the total, we can double that number.

This huge expansion cannot be attributed to any great merit in the English language as such. Rather it must be attributed to historical developments, many of them accidental, by which England (and later Britain) gained a huge empire and then Britain and its former colonies gained influence far beyond the boundaries of that empire. Even by the time that Elizabeth I came to the throne of England, the spread of English had started. An English-speaking area had been established round Dublin in Ireland, within what was called the Pale.

Beyond the Pale there was (from the English viewpoint) no civilisation. The Pale was established by the Normans in the twelfth century, but it persisted, varying in size, until the seventeenth century. Another sign of expansionism was the exploration of Canada by the Cabots in the final years of the fifteenth century, laying the foundation for English claims to Canada. The first years of Elizabeth I’s reign saw further expansionist moves.

Although there had been Norman settlements in Wales, and an English Prince of Wales since 1301, the Statute of Wales in 1535 imposed English as the official language of the country for all legal purposes, and prevented Welsh speakers from holding office unless they used English for official purposes. This was only feasible because there had been an unlegislated imposition of English in the two preceding centuries, with settlements of English-speaking people in Wales, and trade being carried out mainly in English.

By 1553, English ships were trading with West Africa (present-day Nigeria), and the slave trade started some ten years later. In the 1580s the first English settlements were made in North America, in Canada in 1583 and at Roanoke in present-day North Carolina in 1584. The Roanoke settlement remains a puzzle to this day. Although we know that the first English child to be born in North America was born there (and named Virginia in honour of Queen Elizabeth), all the settlers mysteriously disappeared and could not be found when English ships returned – much later than expected – with provisions.

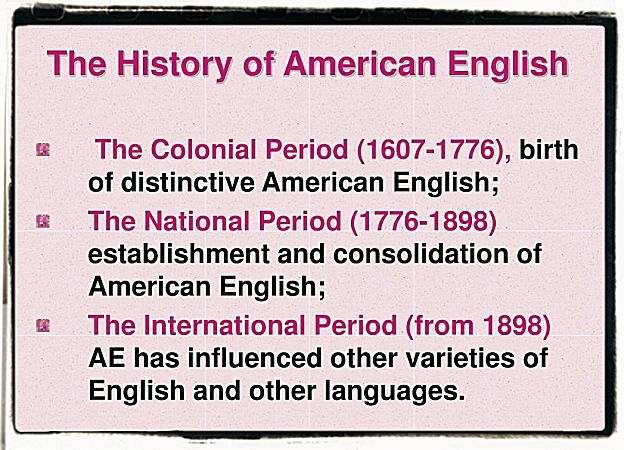

In 1603, with the death of Elizabeth I, James VI of Scotland also became James I of England, and Scotland and England were merged politically into Great Britain. This had the effect of spreading English influence into Scotland, especially through the use of the King James version of the Bible, published in 1611. The year 1607 was a fateful one for the English language. The first lasting settlement in North America was established at Jamestown in Virginia. The settlers who formed the permanent population in this area were largely from the English west country, and traces of their varieties of English can still be found in North American English generally and in the eastern seaboard dialects of Virginia in particular.

The other major event at this time was the plantation of Ulster. Settlements (or plantations) of Englishmen had been tried by Elizabeth as a way of quelling rebellion in Ireland and securing the English, Protestant, throne against the Catholic Irish. James I continued the policy, confiscating lands of Irish nobility who were deemed to have rebelled against English rule, and selling them to English and Scottish settlers who had to fulfill certain criteria, one of which was (in effect) being Protestant.

Although it took a long time for the plantations to have the desired effect, the commonalities between the speech of Northern Ireland and western Lowland Scotland today stem largely from the number of Scots who settled in Ulster from 1607 onwards. The next major settlement in North America took place in 1620, when the Mayflower, carrying people from the eastern counties of England, failed to reach Virginia and landed instead in present-day Massachusetts, where they founded the town of Plymouth.

At about the same time, in 1621, a charter was granted for a Scottish settlement in Nova Scotia, but there was not enough money to pursue the project, and Nova Scotia remained little more than a name on a map for some time after that as far as the British were concerned. We pass quickly over the next hundred years, during which time the British hold on Ireland was strengthened, and the settlement of eastern North America continued.

In 1763, Canada was ceded to the British by the French. “Canada” then referred only to the French-speaking areas, not the large country we know today, which was not to be established for another hundred years. From our point of view this was an important step because it allowed a British foothold in North America to be maintained after the American Declaration of Independence in 1776. The British did not recognise the United States of America until 1783, when disappointed loyalists fled into Canada.

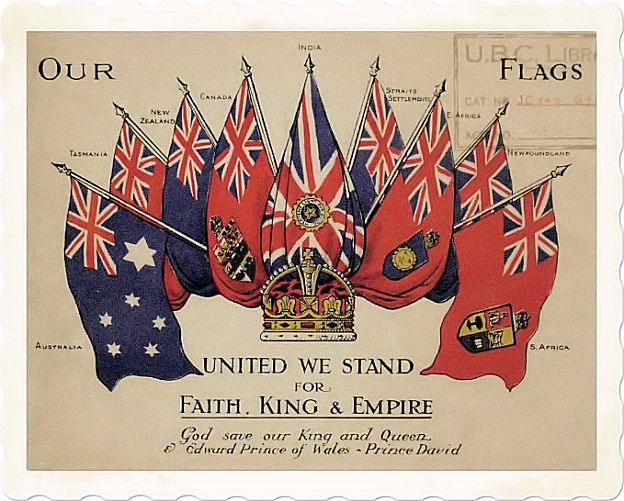

By this time, Captain James Cook had mapped the coastline of New Zealand (1769) and met his first kangaroo (1770). He claimed both Australia and New Zealand for the British crown, though it was not until 1788 that the first penal colony was established at Botany Bay (present day Sydney). That was just a few years before the occupation of the South African Cape Colony in 1795.

So by the opening of the nineteenth century, English had spread to every corner of the world, and in the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries the number of speakers of the language, and the language’s own prestige, grew and grew. In 1800 the population of the United States was about 5.3 million; by 1900 it had grown to 76 million. By the close of the twentieth century it was heading for 250 million.

The growth was achieved by spreading out to cover more land, and by accepting immigrants from elsewhere in the world. In 1803 Louisiana (a much larger area than the current state) was bought from the French; in 1819 Florida was bought from Spain; and all Zorro fans know the story of the California purchase! Many of the immigrants came from the British Isles as a result of the agricultural reforms and other related events that were going on there.

As early as the time of Elizabeth I, agricultural practice was changing in England, with tracts of land under cultivation being made larger for greater economy. For the landowners to get these large tracts of land, the poor were thrown out of their homes and off the land. This led to a gradual deruralisation of the British populace and a move to the cities, which accelerated with the arrival of the industrial revolution and the need for factory workers. Although this trend is visible at least until the end of the nineteenth century, there are two major events which had an effect on the kinds of emigrants from the British Isles who took their English out into the world.

The first was the Highland Clearances, following on from the failure of the second Jacobite rebellion in 1745, as a result of which English had been imposed in much of the Highlands. The population of the area was growing faster than the capacity of the land to feed the people. The two factors of population growth and reduced access to land for crops forced people to emigrate. The same was true in Ireland, whose population in 1841 was over eight million, making it the most densely populated country in Europe at the time. In both countries the smallholders were hindering the emergence of large profitable estates, and were being moved off the land. Then in 1845 came the potato famine.

This hit hardest in Ireland, where between half a million and a million people died (more often of disease brought on by weakness than of actual starvation) in a four-year period. Although the potato was not such an important part of the diet in England and Scotland, it again meant that the land could not carry the population. The twin pressures of lack of food and landowners trying to gain greater incomes from their land meant that emigration was the only alternative to starvation for many people.

The population of Ireland has never recovered. It fell by two million in ten years. In the course of the nineteenth century nearly five million Irish people emigrated to the United States alone (McCrum et al. 1986: 188), and that doesn’t take any account of those who ended up in Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Into the late nineteenth century emigrants from the British Isles to Canada, the United States, Australia and New Zealand were being driven by the same motivation of lack of land and opportunity.

Although this explains how English speakers spread around the world, it does not tell us much about the great political power that has accompanied that spread. The political power grew not only from the number of countries where English-speaking people settled, but from the economic and military strength of those people.

This started in the reign of Elizabeth I, with explorers going out to seek new trade. This was a deliberate policy for Elizabeth, who had inherited a virtually bankrupt nation which became rich during her reign. Although the policy did not keep all subsequent monarchs affluent (James I sold off bits of Ireland partly to help fill his coffers), most of Britain’s wealth came through its trade coupled, in the nineteenth century, with its industrial strength.

At the same time there was a feeling of moral superiority, which gave rise to political and religious evangelicalism, and which allowed the colonisation of much of the world to proceed. The feeling that the British were right and that they were doing everyone a favour by bringing them democracy, bureaucracy, Christianity, literacy and the English language became extraordinarily well established. This unreflecting arrogance seems odd today, but was genuinely felt in the colonial period. It leaves its traces in the reluctance of English-speakers to learn other languages, among other things.

In its turn, US power has been based on industrial and military muscle. From the time the US entered the First World War in 1917 right through to the present, the US has been one of the major military powers in the world. The economic and military might has left behind it traders and soldiers who have had to learn English to do their job properly. Because industry, exploration and military demands needed and contributed to learning, much of scientific discourse came to be carried out primarily in English, especially in the second half of the twentieth century. It is the combination of industry, trade, war and learning all of which use English that has put English in its position as the world’s pre-eminent language. And while Britain and the US have driven that combination of factors, the other countries under discussion here have benefitted from the fact that those two have made English so important.

Well, so now, in order to summarize and point out the main content of this article we must conclude with David Crystal that a language becomes an international language and then eventually a global language for one reason only and that is the power of the people who speak it. There’s nothing intrinsically wonderful about the English language that makes people say, you know, “I want to learn it because it sounds so wonderful or because its structure is such and such “No, its power, power, power”, but power means different things at different times. Now the original source of the power of English came for political reasons, as everybody knows, the power of the British Empire originally, and then eventually the power of the “American Empire.”

Between them English became the dominant voice of that kind of political history. But that’s only one kind of power. A second kind of power, which is also very, very important, is the power of knowledge. The Industrial Revolution arrives in the 17th, 18th centuries, something like two thirds of the people who have made that revolution possible, the people who invented the new roads and textile machines and locomotives and so on, these were English speakers. So English quickly became the language of science and technology, and still is, of course. Something like 80 per cent of all the science in the world is mediated through English, still. So scientific power, technological power.

The third kind of power and probably the most important of all these days is economic power. The fact of the matter is that at the beginning of the 19th century Britain was the most economically powerful nation in the world, it was called “the workshop of the world”. By the end of the 19th century, the United States was the most powerful nation, economically. The only other nation that had real strength in the 19th century was Germany, who invented much of the international banking system, but the First World War changed that balance of power, leaving Britain and America as the two dominant economic voices. So they say “money talks”. Well, what language was it talking? It was talking the pound and the dollar and these days chiefly the dollar. So. that’s the third kind of power.

And then the fourth kind of power is cultural power So most people around the world now encounter English first probably through pop songs or the Internet or something of that kind. English has been the voice of most cultural 20th century developments from radio, television, air traffic control, sea navigation, space travel, marketing, international advertising and all of that, you know, all of these things. When you see posters all over the world advertising Coca Cola or Kellogg’s Cornflakes, this is where you pick up so much English in an everyday kind of Setting. You don’t see any other language remotely achieving that kind of public view. And so these four kinds of power, political, technological, economic and cultural, together, have caused English to become the global language that it is.

Will it stay that way? That will depend on whether those kinds of power maintain. It’s perfectly possible for an alternative power structure to enter the world and for another nation. or another group of nations, to become the dominant voice and to have the dominant power. Nobody would dare predict the future with language, ever. So it’s perfectly possible one day that a different language could become the voice of the planet, it could be Chinese, it could be Arabic, could be Spanish, could be anything, really, it could be Martian, depending upon what happens.

At the moment there’s no likelihood of anything else taking over from English because all these other nations are falling over backwards to learn English. You might expect the Chinese to foster Chinese, well they do, to an extent, but, well, the Chinese are learning English at the moment and have been for decades. So the figures speak for themselves. We’re talking about a world English language-speaking population of something like 2 billion, a third of the world’s population. And. its a figure that’s growing steadily, there’s no sign of its diminution at the moment.

The interesting statistic about that though, is that, of those 2 billion, only about 400 million or so are first language speakers of English, in countries like Britain, the United States. Ireland, Canada. Australia, New Zealand. South Africa, countries of the Caribbean, and a few other territories, which means that for every one native speaker of English there are between four and five non-native speakers of English, which means that the centre of gravity of the language has shifted away from the native speaker to the non-native speaker.

So one can predict that the future of English is going to be increasingly influenced by the patterns of use, that non-native speakers actually manifest. And this is a dramatic change in the history of English, in the history of any language. No language has ever been influenced by a preponderance of non-native speakers before, in the way that English is. And so the future of English is really fascinating from this point of view. I wouldn’t dare predict what its going to sound like and look like in a 100 years’ time.

To learn, to practice and to improve the English Language, the Use of Internet and Marketing Strategies write us, we can guarantee free advice, good tricks, useful cooperation, lot of materials and ideas. Find out more at the following links:

The world of English language ;

On Facebook ;

Videos:

History of English in 10 minutes ;