The reaction to any word may be, in an individual, either a mob-reaction or an individual reaction. It is up to the individual to ask himself: Is my reaction individual, or am I merely reacting from my mob-self? When it comes to the so-called obscene words, I should say that hardly one person in a million escapes mob-reaction.

D.H. Lawrence

Slang or colloquial language of a racy, informal kind; sometimes offensive or abusive language. Slang changes its forms quickly; it is the everyday, conversational usage of working people, but it is often elaborate and metaphorical, rather than simple in construction. Different classes of person and age-groups all have their own kind of slang, or cant, dialect and jargon.

Popularly used as an equivalent to jargon, as collocations like schoolboy slang; drug addicts slang; RAF slang, etc. imply. The term refers to the individual vocabulary used by different social groups. However, jargon is best reserved for technical vocabulary arising from rather specialized needs. In a more general sense “slang” is associated with larger social groups such as adolescents or dialect speakers (e.g. Cockney rhyming slang). Again, it is characteristically associated with very informal “registers”, and speech dialect speakers predominantly; and again it presents an alternative lexis, of an extremely colloquial, non-standard kind, sometimes co-occurring with swearing.

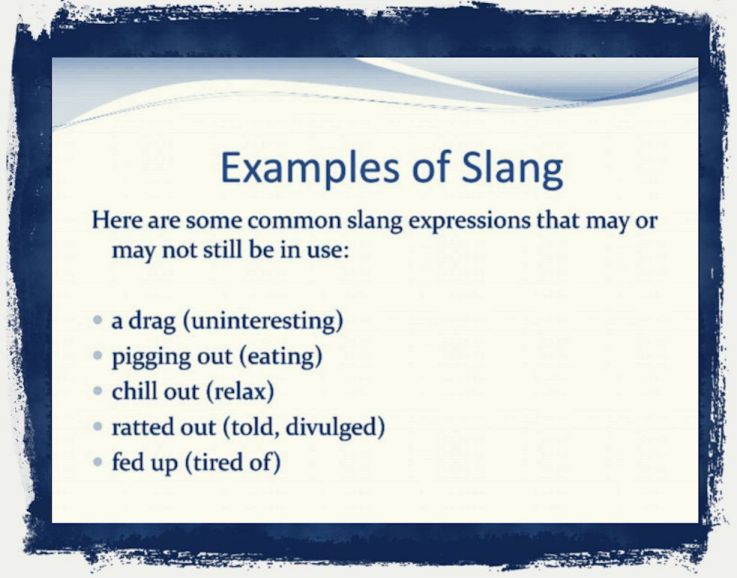

Slang is certainly less socially “acceptable” than jargon, and more socially subversive , to be defined almost as a “deviation” from standard usage. Slang words can come and go very quickly: either passing out of the language completely, or being “promoted” to standard usage. No one says hard cheese or spiffing any more, which sound very Wodehousian. Sonic words considered slang in the eighteenth century are now not: e.g. piano; bully; doggerel. Some words, however, remain this side of respectability for a long time: booze (verb) since the Fourteenth century, for example.

Slang reveals a remarkable “expressiveness” and “creativity” in its forms: making, considerable use of neologism; clipping; sound symbolism; metaphor, etc. Its prime motivation is obviously a desire for novelty of expression: and as Turner (1973) notes, it lacks the finer cognitive distinctions that usually motivates technical jargon. As has often been noted, certain semantic fields seem to attract a wealth of slang terms and idioms: e.g. money (brass; dough; mint; lolly; etc.); head (noodle; noddle; chump; (stewed; sloshed; plastered; half-cut. etc.); nonsense (ballyhoo; Pi block; loaf etc.); drunk cobblers; guff etc. Many are Obviously humorous, and such humour is often exploited in a kind of euphemism, which softens “taboo” subjects, e.g. death (pushing up the daicies; kick the bucket; a stiff).

According to a diffused opinion, the term “slang” indicates a subcultural means of communication whose only purpose is to provide criminals, rappers, punk-rockers and other such characters with a set of wicked words and expressions unintellegible to “normal” and “respectable” people. From this point of view slang is not only a menace to language purity and decency, but also a dangerous source of vice: “if our children learn to name drugs, sooner or later they will start to take them!” Long and thorough researches on the subject on the contrary demonstrated that the above said point of view lacks in objectivity and scientific reliability.

An open minded glance on the matter proves slang to be a rather interesting linguistic process by which people of different social conditions are enabled to make their own language more effective and enjoyable. Generally speaking, slang refers to nonstandard terms or nonstandard usages of standard terms: it is a kind of informal language that generally follows the grammatical patterns of the language from which it stems but that reflects an alternate lexicon with connotations of informality.

Slang provides different symbols from which communication messages can be constructed and, even though we can’t say it is a complete language, like any language it reflects the experiences, beliefs and values of its speakers. This stated, if it is clear that slang “can” be used by crooks and punks, this does not mean that it belongs only to them. As a matter of fact slang has a lot to do with “coolness” rather than with criminality.

Cool is of course a slang word, and it has got many different meanings: for slangsters it is basically a category of the spirit involving a long list of qualities. This adjective can be applied indifferently to people, things or situations, and it means something between calmness, fun, fashion, up-to-date-ness and every other positive condition you could think of. Eventually slang provides its speakers with the coolness standard language is not able to give them. And since many philosophers have taught us that language has a direct influence upon the world that speakers inhabit, it can be rightfully said that slang is a means to make the world a better place.

The word “slang” was used firstly in 1756, “special vocabulary of tramps or thieves,” later “jargon of a particular profession” (1801). The sense of “very informal language characterized by vividness and novelty” is by 1818. The established origin of the word is from the Northern England noun slang “a narrow piece of land running up between other and larger divisions of ground” and the verb slanger “linger, go slowly,” which is of Scandinavian origin (compare Norwegian slenge “hang loose, sling, sway, dangle,” Danish slænge “to throw, sling”). Their common denominator seems to be ‘to move freely in any direction’ [Liberman]. Noun derivatives of these (Danish slænget, Norwegian slenget) mean “a gang, a band,” and Anatoly Liberman compares Old Norse slangi “tramp” and slangr “going astray” (used of sheep). He writes: “It is not uncommon to associate the place designated for a certain group and those who live there with that group’s language. John Fielding and the early writers who knew the noun slang used the phrase slang patter, as though that patter were a kind of talk belonging to some territory.”

So the sense evolution would be from slang “a piece of delimited territory” to “the territory used by tramps for their wandering,” to “their camping ground,” and finally to “the language used there.” The sense shift then passes through itinerant merchants: Hawkers use a special vocabulary and a special intonation when advertising their wares (think of modern auctioneers), and many disparaging, derisive names characterize their speech; charlatan and quack are among them. Liberman concludes: Slang is a dialectal word that reached London from the north and for a long time retained the traces of its low origin. The route was from “territory; turf” to “those who advertise and sell their wares on such a territory,” to “the patter used in advertising the wares,” and to “vulgar language” (later to “any colorful, informal way of expression”).

The language of slang as we said before tends to vary greatly through the diachronic times. What does an Englishman say when he accidentally hits his finger with a hammer, or when he spills a cup of boiling coffee on his shirt? In the good old days, he might have exclaimed “Damn!” “Dash!” or “Drat!” (all of which are concerned with hell or damnation). Nowadays, he is likely to use stronger words, but which also contain four letters. Four letter words are those swear-words which refer to the sexual and excretory functions of the body. The English, it should be noted, tend to get more offended by these terms than they would by blasphemous ones – this is in marked contrast to Italians.

Of the four letter words, one in particular has quite a history of hitting the headlines. Until the 1960s, the word “fuck” didn’t officially exist. Look at any dictionary of the 1950s (or earlier and you will find a yawning gap between the words fuchsite and fucoid. In the 1930s, the celebrated lexicographer Eric Partridge published a Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English. He included an entry on what was then an extremely unconventional word: “f*ck”. Outraged citizens protested and in many libraries the offending volume was kept under lock and key, available only on special request.

Things were to change after an event known as “The Lady Chatterley Trial”‘.” D.H. Lawrence had written his last and most sexually explicit novel, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, in 1928. The famous “f-word” appeared frequently (as indeed did the dreaded” “c-word,” cunt) and no British publisher dared print the original version. When Penguin Books took the brave decision to do so in 1959, they were prosecuted under the Obscene Publications Act. They were acquitted after a brief trial in 1960 and this decision marked the virtual end to literary censorship.

The word fuck is a regular feature of speech these days. Indeed the adjective fucking is so common that it has lost all meaning. This is apparent from the following story, which is told by an angry man: “I got up this fucking morning. I went out the fucking house and started walking to fucking work. As I was walking down the fucking road I heard this fucking noise. It was coming from behind a fucking hedge. I looked over the fucking hedge and saw this couple having sexual intercourse”. Although the word fuck can now be found in dictionaries, it hasn’t lost its ability to offend. Sex was once a taboo subject in the cinema, even if that might seem hard to believe today.

Fifty years ago Hollywood’s Production Code actually forbade the use of such mild words as sex and sexual. All that has changed and these days fuck and fucking can be heard often enough in the cinema. Television, being a “family institution,” remains more conservative: the f-word is carefully dubbed over when movies are shown on TV. This is in spite of the fact that it was first used in a live transmission 20 years ago, by the late theater critic Kenneth Tynan. Television also has rules for less controversial language: the term bloody (generally thought to be a corruption of “By our Lady” can only be used in programs after 9 p.m, when all impressionable young children are for some reason expected to be asleep.

Rude words are also banned from the House of Commons. Even the inoffensive term twerp was deemed “unparliamentary” as recently as 1986 and the speaker was obliged to withdraw the remark. The picture seems to be quite different across the Atlantic. During the Watergate hearings of 1973-4, Congress scrutinized the transcripts of President Nixon’s office tapes. The term “expletive deleted” was used with unbelievable regularity. Contemporary American leaders also use language that would be taboo for their British counterparts. During the Gulf War, President Bush immortalized the term to kick ass (British: arse) in describing military victories over Iraq. General Schwarzkopf was a little more circumspect, even witty. He had no wish to offend anybody by denouncing Iraqi propaganda as bullshit, so he used the euphemism bovine scatology instead. Incidentally, the British equivalent is crap, but God forbid that an officer of Her Majesty should ever use that sort of language on television.

Slang dictionaries online

www.translatebritish.com/dictionary Translate British British Translator & Slang Dictionary Translate British to American & American to British Slang

Britishslang.co.uk British Slang Dictionary of English, Irish, Welsh, Scottish, Cornish, Yorkshire slang … if it’s spoken in the British Isles it’s here.

Dave’s ESL Cafe has a short guide to American slang designed to assist those who are learning English as a second language.

Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE) breaks the U.S. into multiple regions and subregions. It only includes words that are used regionally. Audio clips are included for many words, giving you the opportunity to hear the regional slang word being said.

ManyThings has a list of more than 280 American slang definitions sorted alphabetically. Example sentences are provided with each term to make it easier to understand the correct usage.

Urban Dictionary is a large website that allows users to submit their own definitions for various slang terms. While the quality of the information can sometimes be questionable, this site is often the best resource for learning more about obscure slang usage.

Slang City, although not a dictionary in the traditional sense, is another great resource for anyone interested in learning more about American street slang. This entertaining website features articles, illustrated topical guides to various types of slang, and interactive games such as the “Random Insult Generator.”

You can also read these interesting articles