The economic crisis of 2007-2009 and the following crash.

The former chairman of the US Federal Reserve, Alan Greenspan, one of the most respected gurus of the economic world once said: “I discovered a flaw in the model that I perceived is the critical functioning structure that defines how the world works.” Indeed, it is impossible to make sense of the world today without taking the effects of the financial crisis into account; triggered a decade ago with the collapse of a Wall Street bank, it expanded around the globe with devastating force. Post-truth, populism, the alt-right and other forms of extremism, inequality, the refugee crisis, geopolitical tensions… These are all phenomena that have developed against the backdrop of a crisis that has shaken the very structure of the world as we knew it, and darkened the outlook of the future.

If history can teach us to avoid making the same mistakes again, studying economic story is nothing short of a necessity; especially as the inner workings of the economy are opaque for the majority of us. Based on rigorous analysis, this crisis offers a critical assessment of the insanity of the financial sector and the incompetence of those in power. This is certainly the first crisis of the global age. In order to understand its implications, therefore, you must connect to the housing bubble in countries such as the US, Spain and Ireland, the accelerated model of growth of the Chinese economy, and the political unrest in the countries of the former Soviet Union.

It is the economy stupid! The quote is almost thirty years old but as resonant as ever. Attributed to one of Bill Clinton’s advisors, it can be used as an answer to almost any question. Indeed, it is impossible to make sense of the world today without taking the effects of the financial crisis into account; triggered a decade ago with the collapse of a Wall Street bank, it expanded around the globe with devastating force and as any crash made us learn something.

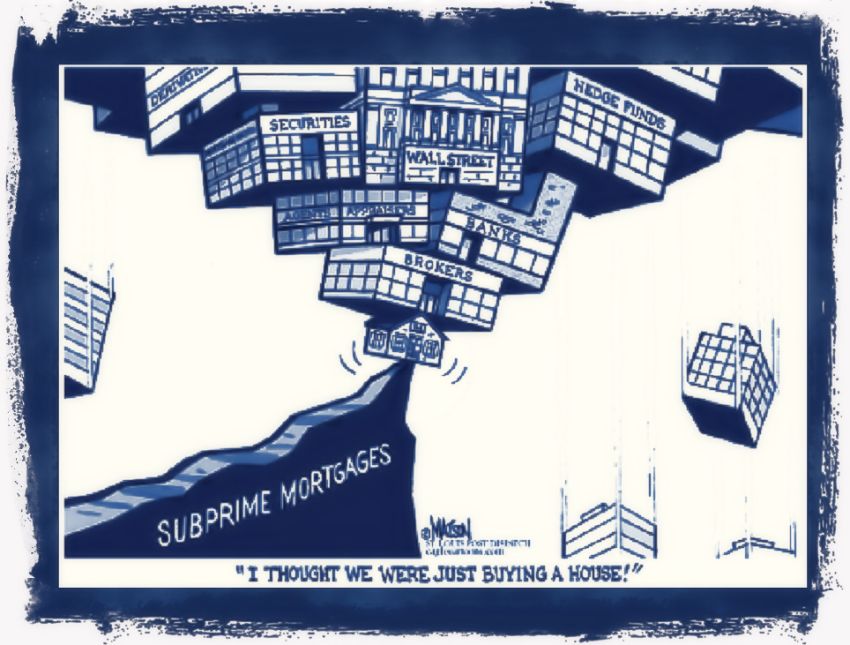

The United States subprime mortgage crisis was a nationwide financial crisis, occurring between 2007 and 2010, that contributed to the U.S. recession of December 2007 – June 2009. It was triggered by a large decline in home prices after the collapse of a housing bubble, leading to mortgage delinquencies and foreclosures and the devaluation of housing-related securities. Declines in residential investment preceded the recession and were followed by reductions in household spending and then business investment. Spending reductions were more significant in areas with a combination of high household debt and larger housing price declines.

The housing bubble preceding the crisis was financed with mortgage-backed securities (MBSes) and collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), which initially offered higher interest rates (i.e. better returns) than government securities, along with attractive risk ratings from rating agencies. While elements of the crisis first became more visible during 2007, several major financial institutions collapsed in September 2008, with significant disruption in the flow of credit to businesses and consumers and the onset of a severe global recession.

There were many causes of the crisis, with commentators assigning different levels of blame to financial institutions, regulators, credit agencies, government housing policies, and consumers, among others. Two proximate causes were the rise in subprime lending and the increase in housing speculation. The percentage of lower-quality subprime mortgages originated during a given year rose from the historical 8% or lower range to approximately 20% from 2004 to 2006, with much higher ratios in some parts of the U.S. A high percentage of these subprime mortgages, over 90% in 2006 for example, were adjustable-rate mortgages.

Housing speculation also increased, with the share of mortgage originations to investors (i.e. those owning homes other than primary residences) rising significantly from around 20% in 2000 to around 35% in 2006–2007. Investors, even those with prime credit ratings, were much more likely to default than non-investors when prices fell. These changes were part of a broader trend of lowered lending standards and higher-risk mortgage products, which contributed to U.S. households becoming increasingly indebted. The ratio of household debt to disposable personal income rose from 77% in 1990 to 127% by the end of 2007.

When U.S. home prices declined steeply after peaking in mid-2006, it became more difficult for borrowers to refinance their loans. As adjustable-rate mortgages began to reset at higher interest rates (causing higher monthly payments), mortgage delinquencies soared. Securities backed with mortgages, including subprime mortgages, widely held by financial firms globally, lost most of their value. Global investors also drastically reduced purchases of mortgage-backed debt and other securities as part of a decline in the capacity and willingness of the private financial system to support lending. Concerns about the soundness of U.S. credit and financial markets led to tightening credit around the world and slowing economic growth in the U.S. and Europe.

The crisis had severe, long-lasting consequences for the U.S. and European economies. The U.S. entered a deep recession, with nearly 9 million jobs lost during 2008 and 2009, roughly 6% of the workforce. The number of jobs did not return to the December 2007 pre-crisis peak until May 2014. U.S. household net worth declined by nearly $13 trillion (20%) from its Q2 2007 pre-crisis peak, recovering by Q4 2012. U.S. housing prices fell nearly 30% on average and the U.S. stock market fell approximately 50% by early 2009, with stocks regaining their December 2007 level during September 2012.

One estimate of lost output and income from the crisis comes to “at least 40% of 2007 gross domestic product”. Europe also continued to struggle with its own economic crisis, with elevated unemployment and severe banking impairments estimated at €940 billion between 2008 and 2012. As of January 2018, U.S. bailout funds had been fully recovered by the government, when interest on loans is taken into consideration. A total of $626B was invested, loaned, or granted due to various bailout measures, while $390B had been returned to the Treasury. The Treasury had earned another $323B in interest on bailout loans, resulting in an $87B profit.

We have all been affected by the financial crisis in some way; be it through unemployment, increasing housing prices, evictions, or cuts to the welfare systems. We may be familiar with Occupy Wall Street, subprime mortgages, bank bailouts and the credit crunch – but how did all these come to pass? British economic historian Adam Tooze set out to explain the financial crisis in one detailed yet accessible book, – Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crisis Changed the World -, and he explained: “What my book attempts to do is to spell out the economic logic of this crisis, to uncover the new processes through which it propagated, to reveal also some aspects of the way in which economists have come to understand the crisis, and to spell out the political and geopolitical ramifications of these events placing the crisis in the context of transatlantic relations and geopolitics in the wake of the Cold War”.

Tooze points to one identifiable starting point of the financial crisis: the collapse of Lehman Brothers, an investment bank that dealt with extremely complex financial products called “derivatives”. These products consisted basically of loans, the so-called “subprime mortgages” made to people that couldn’t normally afford one. The trick was to group these bad loans with good ones, and sell them in bulky to investors. But once people started to default on their payments, the bubble burst dramatically. “First and foremost, it’s a crisis of the Wall Street banks symbolised by the failure of Lehman on the 15th of September, 2008.

And that’s a story which we’ve come to think of as being integrally related to the sophistication and complexity of financial engineering. It’s that kind of technology, a technological system, that we don’t really understand, that is running out of controls , that the “wizards” of Wall Street have created but don’t really control and is now going to blow the global economy up. Behind that, stands the story of an American society, fundamentally out of touch with its limited means being fed an endless diet of the propaganda of credit and consumption. Surely one of the most irresponsible marketing campaigns ever launched by a bank: “Open account, satisfy your desires by taking out credit, live richly.”

But, as Tooze explains, the domino effect of the subprime crisis was global and, quite possibly, the worst in history to date. “It’s very important to realize the significance of this. We are not talking about one of the regular bouts of the flue that the global economy is subject to in the course of the regular business cycle. We are not talking about the kind of sclerosis that might overcome the global economy. We are talking about here, the risk of an acute massive and fatal heart attack within the global financial system. So this is a shock to the entire Trans-Atlantic economy, astonishingly synchronized. And I think it’s very important just to appreciate how severe, how dramatic, how cataclysmic this shock appeared to be. What we were witnessing in September and October 2008, was quite simply the worst financial crisis the world had ever seen.