The heart of melancholy, an article about the famous book by Robert Burton The Anatomy of Melancholy published in 1621 but still very worth reading today. In this short essay you will find also some very interesting quotes by the author himself.

There is a kind of sadness that comes from knowing too much, from seeing the world as it truly is. It is the sadness of understanding that life is not a grand adventure, but a series of small, insignificant moments, that love is not a fairy tale, but a fragile, fleeting emotion, that happiness is not a permanent state, but a rare, fleeting glimpse of something we can never hold onto. And in that understanding, there is a profound loneliness, a sense of being cut off from the world, from other people, from oneself.

Virginia Woolf

There ’s naught in this life sweet, If man were wise to see ’t, But only melancholy; O sweetest Melancholy!

Robert Burton

Great men are always of a nature originally melancholy.

Aristotle

In every room there is a smiling photograph of my mother, her sweet image increases my melancholy and reminds me at every moment that only death can put an end to my suffering.

Carl William Brown

My melancholy is the most faithful mistress I have known; what wonder, then, that I love her in return.

Sailing in a sea of memories, melancholy attacks me and my only relief is to try to alleviate the suffering by lashing out at human stupidity.

Carl William Brown

Melancholy: an appetite no misery satisfies.

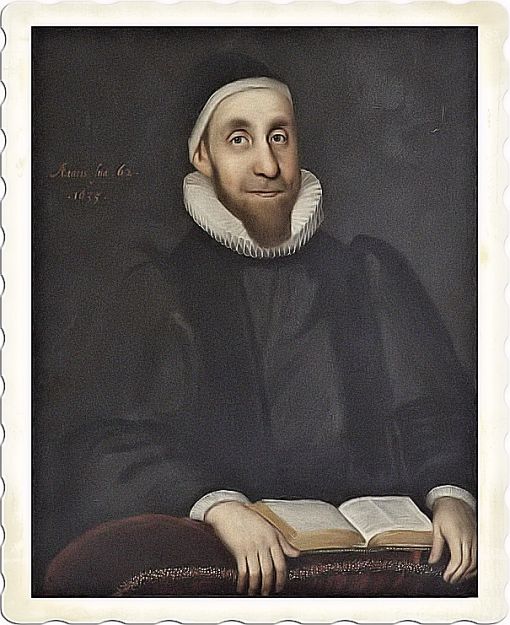

Renaissance author Robert Burton (1577-1640) was an English scholar, clergyman, and writer, best known for his monumental work “The Anatomy of Melancholy.” Born in Leicestershire, England, Burton studied at Oxford University, where he excelled in academics, eventually becoming a fellow of Christ Church college.

Despite his academic achievements, Burton struggled with melancholy himself, which deeply influenced his literary endeavors. He found solace in extensive reading and writing, and in 1621, he published his magnum opus, “The Anatomy of Melancholy.” This sprawling work explores the causes, symptoms, and cures of melancholy, drawing on a wide range of sources from classical literature to contemporary medical texts.

Throughout his life, Burton remained devoted to scholarship and the pursuit of knowledge. He continued to revise and expand “The Anatomy of Melancholy” until his death, producing multiple editions that cemented his reputation as one of the foremost scholars of his time.

Robert Burton’s legacy endures through his influential writings, which continue to be studied and admired for their intellectual depth and literary brilliance. He is remembered not only as a prolific author but also as a compassionate observer of the complexities of human experience.

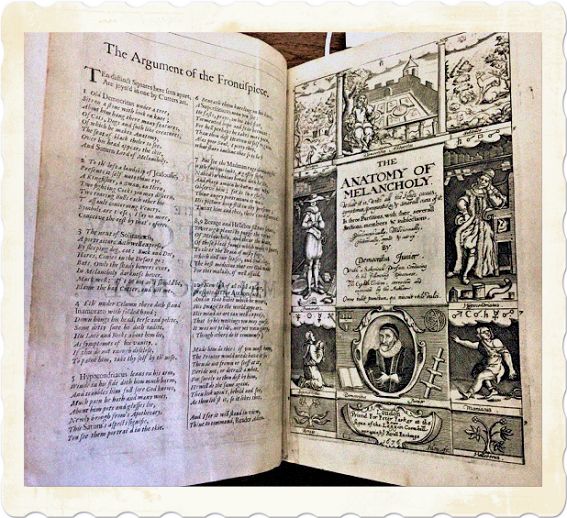

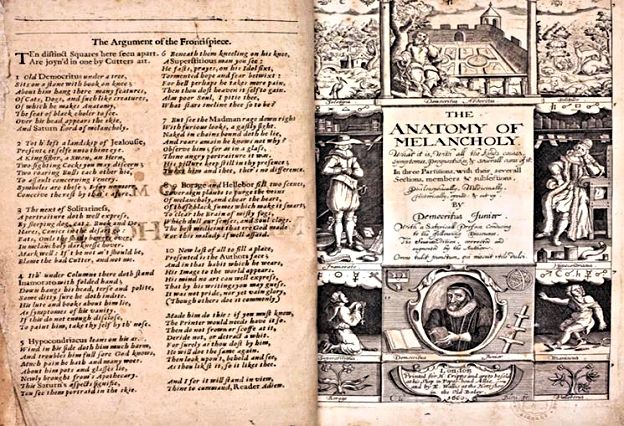

Burton’s most famous work and greatest achievement was The Anatomy of Melancholy. The text is renowned for its erudition, wit, and profound insights into the human condition. It covers an astonishing array of topics, including philosophy, psychology, medicine, religion, and literature, reflecting Burton’s wide-ranging intellect and eclectic interests. First published in 1621, it was reprinted with additions from Burton no fewer than five times. A digressive and labyrinthine work, Burton wrote as much to alleviate his own melancholy as to help others. The final edition totalled more than 500,000 words. The book is permeated by quotations from and paraphrases of many authorities, both classical and contemporary, the culmination of a lifetime of erudition.

Burton died in 1640. In the university, his death was (probably falsely) rumoured to be have been a suicide. His large personal library was divided between the Bodleian and Christ Church. The Anatomy was perused and plagiarised by many authors during his lifetime and after his death, but entered a lull in popularity through the 18th century. It was only the revelation of Laurence Sterne’s plagiarism that revived interest in Burton’s work into the 19th century, especially among the Romantics. The Anatomy received more academic attention in the 20th and 21st centuries. Whatever his popularity, Burton has always attracted distinguished readers, including Samuel Johnson, Benjamin Franklin, John Keats, William Osler, and Samuel Beckett.

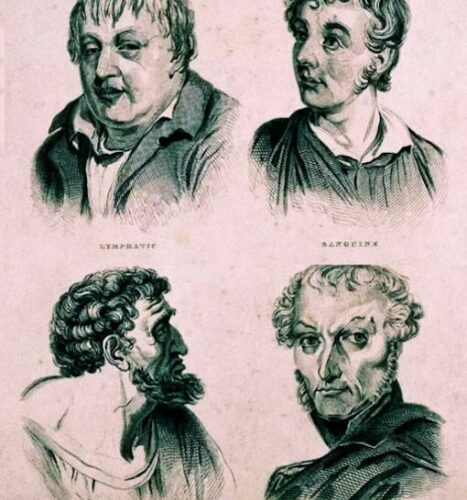

He wrote Anatomy of Melancholy while he suffered in its grip. Considered the most significant publication of his career, the book explores different types of melancholy, presented according to humoral theory, that is the combinations, in men and women ( the microcosm ) of the qualities, or contraries. In primitive physiology, the four principal bodily fluids in their combinations produce the temperaments or “complexions”.

Humorism, the humoral theory, or humoralism, was a system of medicine detailing a supposed makeup and workings of the human body, adopted by Ancient Greek and Roman physicians and philosophers. This theory dates bach to Hippocrates who is usually credited with applying this idea to medicine. In contrast to Alcmaeon, Hippocrates suggested that humors are the vital bodily fluids: blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile.

These “humors,” with their properties and effects – at least in the Middle Ages – are, respectively: Blood (hot and moist) – cheerfulness, warmth of feeling; Choler ( hot and dry ) – a quick, angry temper; Phlegm ( cold and moist) – dull sluggishness; Melancholy (cold and dry) – fretful depression. The Renaissance introduced the concept of “artificial” humors – e.g. scholars’ and artists’ melancholy, creative brooding. The humors, the temperaments, and the four elements of the macrocosm, or universe, were all looked upon as interrelated.

To these humours you may add serum, which is the matter of urine, and those excrementitious humours of the third concoction, sweat and tears. Spirit is a most subtle vapour, which is expressed from the blood, and instrument of the soul, to perform all his actions; a common tie or medium between the body and the soul, as some will have it; or as Paracelsus, a fourth soul of itself.

As a minister, Burton viewed melancholy as a spiritual affliction, and one specific type of “religious melancholy” was made worse by leading a sinful life. Although the book was a response to the debates within English religion during the 1620s-1630s, Burton’s primary concern is curing religious melancholy. He advised prayer as a solution for those suffering from the illness. Later writers were influenced by his combination of scholarship, humor, and creativity.

“The Anatomy of Melancholy” is certainly a vast and multifaceted work that delves into numerous themes and subjects. The work is a comprehensive exploration of the human condition, touching on themes of mental health, philosophy, religion, literature, and science. It offers readers a rich tapestry of ideas and insights that continue to resonate across centuries.

As the title suggests, the central theme of the book is melancholy, which in Burton’s time referred to a state of profound sadness or depression. Burton examines the causes, symptoms, and treatments of melancholy, drawing on medical, philosophical, and literary sources to offer insights into the nature of mental health.

In attacking his stated subject, Burton drew from nearly every science of his day, including psychology and physiology, but also astronomy, meteorology, and theology, and even astrology and demonology… Much of the book consists of quotations from various ancient and mediæval medical authorities, beginning with Hippocrates, Aristotle, and Galen. Hence the Anatomy is filled with more or less pertinent references to the works of others. A competent Latinist, Burton also included a great deal of Latin poetry in the Anatomy, and many of his inclusions from ancient sources are left untranslated in the text.

So Burton explores the complexities of human nature and the range of emotions experienced by individuals. He examines the various factors that contribute to melancholy, including temperament, lifestyle, and external circumstances, offering a nuanced understanding of the human psyche. He incorporates medical knowledge and scientific theories of his time into his discussion of melancholy. He examines the physiological and psychological aspects of the condition, as well as different medical treatments and remedies.

The author engages with philosophical questions about the nature of existence, happiness, and the meaning of life. Burton discusses different philosophical perspectives on melancholy, drawing on the works of classical philosophers as well as contemporary thinkers. He also examines the role of religion and spirituality in coping with melancholy and finding meaning in life. He discusses religious beliefs and practices from various traditions, exploring how they address questions of suffering, redemption, and salvation.

The book is rich in literary references, with Burton drawing on a wide range of literary works from classical antiquity to his own time. He discusses the representation of melancholy in literature and explores how cultural attitudes toward melancholy have evolved over time.

In the Renaissance, several informal ways coexisted of talking about the relation which we now see as one of mind and body. From Aristotelian tradition the concept of three orders of soul was maintained: in ascending order these were the vegetable (the “life,” immobile and inactive, of plants), the animal (accounting for the behavior of beasts), and the rational (the power of reason, often associated with language as well as diought, in men).

Therefore the psychological tracts of the English Renaissance were “a chaotic jumble of ambiguous or contradictory fact and theory,” often more physiological than psychological. Forest concluded that Elizabethan psychology did not exist as a coherent body of belief. Contemporary dramatists could choose illustrations at will from bits and pieces of outmoded medieval scientific “facts” or from “vague general notions” or personal observations.’ In this sense The Anatomy of Melancholy, may help us to clarify Elizabethan psychology while suggesting some possible solutions to the matter.

In the Anthology of the English Literature we read this analyzes of the author. The life of this remarkable figure is so nearly co-extensive with his one great work that its mere chronology yields little of interest: he was born in Leicestershire, came to Oxford (to Brasenose College) in 1593, and in 1599 was elected Student of Christ Church, “the most flourishing college of Europe.” He took his B.A. in 1602 there, and his M.A. in 1605, and lived at the college for the rest of his life. In 1616 he became vicar of St. Thomas’s church in Oxford and held, toward the end of his life, two absentee livings; but his time was mainly spent in reading and in composing his Anatomy, that vast systematic work which started out as a compendium of medical and moral knowledge and ended up, constantly revised in five editions before its author’s death, as a study of the morbidity of its own studiousness. From its first appearance in 1621 Burton kept augmenting his compilation of learned opinion, allusion, and eloquence, adding new light as it came into his dark tower of self-consciousness through the windows of countless books.

If The Anatomy of Melancholy is about the human psyche’s entire range of states – manic, depressed, light, dark, high, and low, and the ways in which they lead to each other – it is also about the very condition of being learned. Burton’s systematic structure embraces physiology, medicine, moral philosophy, and literary history; it moves from detailed exposition of received pre-scientific doctrine to long, wide-ranging essays on such questions as the woes and miseries of scholars, or the effects of literary eroticism (Burton calls it “heroic love”) on psychic stability.

Burton’s melancholy is not only the totality of the types he classifies so exhaustively. A cult of melancholia was fashionable in early Jacobean England, particularly around the Inns of Court, the theaters, and the haunts of young men down from the universities. This melancholy was associated with the intellectual life which – through lack of preferment at court and insufficient civil service posts to absorb the over-educated and under-inherited – could not fulfill itself. Such diverse Shakespearean figures as Hamlet and Malvolio reflect this condition, which for Burton is almost identical with the human one. His own private melancholy is, ultimately, that of the book itself, a strange mixture of inner enterprise and practical idleness, as far removed from the healthy, somber joy of Milton’s II Penseroso as from the massive brooding figure of intellect abandoned in Durer’s Melancolia.

The introduction to Burton’s work, explaining why he adopts the pseudonym of Democritus Jr., is a masterpiece of self-revelation through disguise, moving at times beyond even the candor and wisdom of Montaigne, discussing its own prose style as if it were an inner life; apologizing for the intrusions of its own English into its mosaic of Latin quotations (the interior dialogue of the whole work is between scholar and books, English and Latin); gloomily propounding a scholarly utopia based upon the certain conviction of human imperfectibility;

and refurbishing its mythical progenitor, the laughing Greek atomist Democritus, into an ancestor of the self-contemplating lyricist of the late eighteenth century – that poet of the crucial modern mode, the therapeutic work, whose internal sanity is its author’s only hedge against madness.

Quotes and thoughts from The Anatomy of Melancholy

I’ll change my state with any wretch

Thou canst from gaol of dunghill fetch.

My pain’s past cure, another hell;

I may not in this torment dwell.

Now desperate I hate my life,

Lend me a halter or a knife!

All my griefs to this are jolly,

Naught so damned as melancholy.

Robert Burton

Believe the experienced Robert. Believe Robert, who has tried it. (Lat., Experto crede Roberto.)

Robert Burton

No rule is so general, which admits not some exception.

Robert Burton

Penny wise, pound foolish.

Robert Burton

Hold one another’s noses to the grindstone hard.

Robert Burton

Going as if he trod upon eggs.

Robert Burton

There ’s naught in this life sweet, If man were wise to see ’t, But only melancholy; O sweetest Melancholy!

Robert Burton

Melancholy, the subject of our present discourse, is either in disposition or in habit… This Melancholy of which we are to treat, is a habit, a serious ailment, a settled humour, as Aurelianus and others call it, not errant, but fixed: and as it was long increasing, so, now being (pleasant or painful) grown to a habit, it will hardly be removed.

Robert Burton

Employment, which Galen calls ‘Nature’s Physician,’ is so essential to human happiness that indolence is justly considered as the mother of misery.

Robert Burton

Gluttony is the source of all our infirmities, and the fountain of all our diseases. As a lamp is choked by a superabundance of oil, a fire extinguished by excess of fuel, so is the natural health of the body destroyed by intemperate diet.

Robert Burton

Restore a man to his health, his purse lies open to thee.

Robert Burton

I may not here omit those two main plagues, and common dotages of human kind, wine and women, which have infatuated and besotted myriads of people. They go commonly together.

Robert Burton

Tobacco, divine, rare, superexcellent tobacco, which goes far beyond all the panaceas, potable gold, and philosophers’ stones, a sovereign remedy to all diseases but as it is commonly abused by most men, which take it as tinkers do ale. ‘Tis a plague, a mischief, a violent purger of goods, lands, health; hellish, devilish and damned tobacco, the ruin and overthrow of body and soul.

Robert Burton

Felix Plater notes of some young physicians that study to cure diseases catch them themselves will be sick and appropriate all symptoms they find related of others to their own persons.

Robert Burton

One religion is as true as another.

Robert Burton

I may not here omit those two main plagues, and common dotages of human kind, wine and women, which have infatuated and besotted myriads of people. They go commonly together.

Robert Burton

All poets are mad.

Robert Burton

We can say nothing but what hath been said.

Robert Burton

The fear of some divine and supreme powers, keeps men in obedience.

Robert Burton

No rule is so general, which admits not some exception.

Robert Burton

They lard their lean books with the fat of others’ works.

Robert Burton

Hannibal, as he had mighty virtues, so had he many vices; he had two distinct persons in him.

Robert Burton

Every man hath a good and a bad angel attending on him in particular, all his life long.

Robert Burton

Why doth one man’s yawning make another yawn?

Robert Burton

[Diseases] crucify the soul of man, attenuate our bodies, dry them, wither them, shrivel them up like old apples, make them so many anatomies.

Robert Burton

Like a hog, or dog in the manger, he doth only keep it because it shall do nobody else good, hurting himself and others.

Robert Burton

I may not here omit those two main plagues and common dotages of human kind, wine and women, which have infatuated and besotted myriads of people; they go commonly together.

Robert Burton

Machiavel says virtue and riches seldom settle on one man.

Robert Burton

Many things happen between the cup and the lip.

Robert Burton

Big stools, small hospitals, Small stools, big hospitals.

Robert Burton

The falling out of lovers is the renewing of love.

Robert Burton

A mere scholar, a mere ass.

Robert Burton

What can’t be cured must be endured.

Robert Burton

They are proud in humility, proud that they are not proud.

Robert Burton

Hope and patience are two sovereign remedies for all, the surest reposals, the softest cushions to lean on in adversity.

Robert Burton

A blow with a word strikes deeper than a blow with a sword.

Robert Burton

Idleness is an appendix to nobility.

Robert Burton

England is paradise for women, and hell for horses: Italy is a paradise for horses, hell for women.

Robert Burton

One was never married, and that’s his hell; another is, and that’s his plague.

Robert Burton

The devil is the author of confusion.

Robert Burton

Almost in every kingdom the most ancient families have been at first princes’ bastards.

Robert Burton

One was never married, and that’s his hell; another is, and that’s his plague.

Robert Burton

And now some proverbs

Make a virtue of necessity.

Robert Burton

Matches are made in heaven.

Robert Burton

These crocodile tears.

Robert Burton

Set a beggar on horseback and he will ride a gallop.

Robert Burton

Every man for himself, his own ends, the Devil for all.

Robert Burton

As clear and as manifest as the nose in a man’s face.

Robert Burton

Where God hath a temple, the Devil will have a chapel.

Robert Burton

He is born naked, and falls a-whining at the first.

Robert Burton

I had not time to lick it into form, as a bear doth her young ones.

Robert Burton

Like the watermen that row one way and look another.

Robert Burton

You can also read: