Poetry and poems, the works of poets, the art of words, an abridged article and some quotes by famous authors, a selection of poems and a comment by Carl William Brown.

Everywhere I go I find that a poet has been there before me.

Sigmund Freud

And as imagination bodies forth the forms of things unknown, the poet’s pen turns them to shapes and gives to airy nothing a local habitation and a name.

William Shakespeare

Genuine poetry can communicate before it is understood.

T. S. Eliot

Poetry comes to man as consolation in the form of beauty and allows even the horrid to be loved and contemplated: it makes the disgusting and the sublime compatible, in the perfection of the figure.

Salvatore Natoli

Poetry is detachment, distance, absence, separateness, illness, delirium, sound and, above all, urgency, life, suffering. It is the flow of intolerance of being there. It is the resonance of saying beyond the concept. It is the abyss that separates oral and written.

Carmelo Bene

In poetry and in eloquence the beautiful and grand must spring from the commonplace…. All that remains for us is to be new while repeating the old, and to be ourselves in becoming the echo of the whole world.

Alexandre Vinet

A poet is, before anything else, a person who is passionately in love with language.

W. H. Auden

I was reading the dictionary. I thought it was a poem about everything.

Steven Wright

One merit of poetry few persons will deny: it says more and in fewer words than prose.

Voltaire

Not only every great poet, but every genuine, but lesser poet, fulfils once for all some possibility of language, and so leaves one possibility less for his successors.

T. S. Eliot

The study of science teaches young men to think, while study of the classics teaches them to express thought.

John Stuart Mill

The lunatic, the lover and the poet are of imagination all compact, they have such seething brains, such shaping fantasies, that apprehend, more than cool reason ever comprehends.

William Shakespeare

Poetry is nearer to vital truth than history.

Plato

What the dead had no speech for, when living, They can tell you, being dead: the communication Of the dead is tongued with fire beyond the language of the living.

T.S. Eliot, Four Quartets

The purpose of literature is to turn blood into ink.

T. S. Eliot

Poetry lifts the veil from the hidden beauty of the world, and makes familiar objects be as if they were not familiar.

Percy Bysshe Shelley

What we call the beginning is often the end. And to make an end is to make a beginning. The end is where we start from.

T. S. Eliot

We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.

T. S. Eliot

We know too much, and are convinced of too little. Our literature is a substitute for religion, and so is our religion.

T. S. Eliot

A poem contains the same elements as a prose composition; the difference therefore must consist in a different combination of them, in consequence of a different object being proposed. According to the difference of the object will be the difference of the combination. it is possible, that the object may be merely to facilitate the recollection of any given facts or observations by artificial arrangement; and the composition will be a poem, merely because it is distinguished from prose by metre, or by rhyme, or by both conjointly.

In this, the lowest sense, a man might attribute the name of a poem to the well-known enumeration of the days in the several months; Thirty days hath September, April, June, and November, etc. and others of the same class and purpose. And as a particular pleasure is found in anticipating the recurrence of sounds and quantities, all compositions that have this charm super-added, whatever be their contents, may be entitled poems.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

The true spirit of delight, the exaltation, the sense of being more than Man, which is the touchstone of the highest excellence, is to be found in mathematics as surely as poetry.

Bertrand Russell

Ordinary people are not interested in poets thoughts, much less in their works, real poets on the other hand are not very interested in the fate of the inhabitants of this filthy planet! As Cecco Angiolieri put it, If I were fire, I would burn the world; if I were the wind, I would hit it with storms; if I were water, I would drown it; If I were God, I would make it sink.

Carl William Brown

A poem begins with a lump in the throat; a homesickness or a love sickness. It is a reaching-out toward expression; an effort to find fulfillment. A complete poem is one where an emotion has found its thought and the thought has found words.

Robert Frost

The poet sees, at the same time and from a single point, what is visible to two, in isolation.

Boris Pasternak

To see a World in a Grain of Sand, And a Heaven in a Wild Flower, Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand, And Eternity in an hour…

William Blake

Poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility.

William Wordsworth, Lyrical Ballads

Poetry is a form of imaginative literary expression that makes its effect by the sound and imagery of its language. The word, often used synonymously with the term verse, is essentially rhythmic and usually metrical, and it frequently has a stanzaic structure. It is in these characteristics that the difference between poetry and other kinds of imaginative writing can be discerned.

The term derives from Greek and it means “creator”, and therefore “Poem” means something created; it is a vague definition, referring, like the word Verse, to literary compositions which are not in prose. Poems are expressed in a language which has been given some sense of pattern or organization to do with the sounds of its words, its imagery, syntax, or any other linguistic element. Poesis (Gk poiesis, from poiein,’ to make’), thus poesis denotes ‘making’ in general, but in particular the making of poetry. The word came into the English language as ‘poesie’ in the 14th c. Later in that century the word ‘poetrie’ (from L. poetria) word was also introduced. They were frequently used synonymously. Eventually poetry supplanted poesy.

Poetry is one of the most ancient and widespread of the arts. Originally fused with music in song, it gained independent existence in ancient times – in the Western world, at least as early as the classical era. Where poetry exists apart from music, it has substituted for lost musical rhythms its own purely linguistic one. It is this rhythmic use of language that most easily distinguishes poetry from imaginative prose, the other great division of literature, and that forms the basis of the dictionary definition of poetry as “metrical writings.”

This definition does not, however, include cadenced poetry (as in the Bible) or modern free verse; both types of verse are rhythmic but not strictly metrical. Nor does it take into account the unwritten songs of many cultures past and present. It is, however, a useful starting point for considering what is now commonly meant by the word poetry.

Enough poetry has come down from ancient times, however, to suggest certain enduring aspects of poetic expression, whatever the time or culture. In Egyptian hieroglyphic inscriptions of about 2600 BC are found kinds of poetry (evidently songs, although only the text, not the music, is preserved) still familiar today: laments, odes, elegies, hymns. The many songs relating to religion (an emphasis true also of such other ancient poetries as Sumerian, Assyro-Babylonian, Hittite, and Hebrew) support the hypothesis that the origins of poetry can be found in the communal expression, probably originally taking the form of dance, of the religious spirit.

Thus, the dance rhythm could be marked not only by clapping, stamping, or rhythmic cries, but by chanting or otherwise intoning or singing words. Song, then, became the progenitor of both poetry and instrumental music. Work songs (a type also found in Egyptian tomb inscriptions of the 3rd millennium BC), lullabies, play songs, and other songs accompanying rhythmic activity probably developed nearly simultaneously with religious songs. The ritual aspect of poetry is still evident in the songs of many native cultures, as in this Navajo incantation for rain, translated by the Irish-born American ethnologist Washington Matthews.

Not just lyric poetry but narrative verse as well may have had its origins in the religious impulse. The earliest narrative songs, or epics, tell the myths of creation and of the gods; later epics treat the lives of godlike heroes; and still later ones deal with the lives of historical heroes. The range is from the Babylonian creation myth and the Gilgamesh epic to the Greek Iliad and Odyssey of Homer, from the Indian Ramayana and Mahabharata to the medieval French Song of Roland and the Anglo-Saxon Beowulf. It is interesting that dramatic poetry was twice born in the West, both times in a religious context: first in ancient Greek festivals, then in medieval church ritual (perhaps with the assistance of much older surviving folk rituals).

As the earliest examples of poetry make clear, however, such ritual origins were expanded on very early. Not all songs existed solely for the practical purposes of propitiating the gods, smoothing the course of the soul’s voyage after death, assuring the outcome of a battle, or influencing natural phenomena. When the tradition of the sung poem yielded to the written tradition—that is, when words were selected and ordered apart from melodic needs—greater complexities of content, syntax, form, and sound became possible. At the other extreme from music, sound all but vanishes in the new emphasis on the visual, or written, aspect of poetry.

Compression, extensive use of imagery, and a strong emotional – and frequently sensuous – component are characteristic of the great grab bag of poems called lyric. The other major divisions of poetry, narrative (epics, ballads, metrical romances, verse tales) and dramatic (poetry as direct speech in specified circumstances), are more amenable to characterization. Lyric poetry, however, covers everything from hymns, lullabies, drinking songs, and folk songs to the huge variety of love songs and poems; from savage political satires to rarefied philosophical poetry; from verse epistles to odes; and from 2-line epigrams or 14-line sonnets to lengthy reflective lyrics and substantial elegies.

The content of lyric poetry is as varied as the concerns of human beings in every period and in every corner of the globe. A clear distinction exists between poetry as pure art form and most so-called didactic poetry, which at its extreme is merely material that has been versified as an aid to memory or to make the learning process more pleasant. Where the emphasis is on communication of knowledge for its own sake or on practical instruction, the designation poetry is rather a misnomer; in his Georgics, Vergil actually tried to teach readers how to farm.

Among lyric poets, the Japanese are unequalled in the extreme compression of their poetry. Two favorite forms are the tanka, which has had a continuous tradition of some 1300 years, and the haiku, which dates from the 16th century and had a marked effect on Western poets at the beginning of the 20th century. Both forms are unrhymed and in syllabic meter: The tanka is five lines of five, seven, five, seven, and seven syllables, and the haiku is three lines of five, seven, and five syllables. (Longer poems also use these five- and seven-syllable lines, and shorter poems are frequently linked into sequences or are carefully arranged in anthologies to provide a cumulative effect.)

Some of the short poems by one of the major 20th-century American poets, Ezra Pound, capture much of the haiku quality. His “Fan-Piece, for Her Imperial Lord,” for instance, although based on a 1st-century BC Chinese poem (much longer in the original but still terse by Western standards), is quite Japanese in its prosody and effect. A poem generally has a very different rhythm from that of ordinary literary prose, although it is true that the two art forms exist on a continuum and metrical patterns are discernible, irregularly, in good prose. An excellent example may be found in the highly concentrated rhythmic sentences in Ulysses by the Irish novelist James Joyce.

Many poems have vanished over the millennia, either because they existed only in the oral tradition and were eventually forgotten, or because so many manuscripts disintegrated or were destroyed. Some of the destruction was by natural processes; some occurred in the wanton pillaging of libraries and centers of learning; and some – as in the case of one of history’s greatest lyric poets, the Greek Sappho – because of bigotry. During the Christian era Sappho’s writings were condemned to be burned, and only about 700 lines remain – saved because they were included in uncondemned anthologies, or were quoted by other writers whose works survived, or because Egyptian embalmers chanced to wrap their mummies with strips of papyrus on which her verses were written.

Of some other Greek writers only the names survive, but not a line of poetry. Closer to the present, the Old English epic Beowulf, the most important poem extant from Anglo-Saxon England, exists in but one manuscript; indeed, from centuries of Old English alliterative poetry only five manuscripts are known to have survived. The invention of printing in the 15th century enormously improved the chances of a book’s survival, and the technological advances of the 20th century in data storage and retrieval make it theoretically possible to preserve any poem. Compared with what is extant from the last 5000 years, future generations of readers will have access to a tremendous quantity of verse from the past.

Technological advances such as the computer will probably change the shape of poetry, but not its importance, for poetry has shown itself to be as adaptable as any other art. While this is less obvious in restrictive societies, in which poetry may be perverted for propaganda purposes and where the best work often goes underground, the achievements of poets in many countries in the 20th century augur well for the future. Works by poets in the United States, Great Britain, and in Latin America and Spain – to mention only a few of the areas where poetry continues to flourish and evolve- testify to its durability.

In the U.S., numerous small magazines are devoted to publishing new poetry, many universities have a “poet-in-residence” on the faculty, and poetry readings by established and new writers are a feature of cultural life on and off campus. Anyway poetry is not to be considered absolutely a superior form of creation; not necessarily therefore, more serious. Aristophanes, Chaucer, Ben Jonson, Donne, Marvell, Pope, Byron and Auden, to name just a few have all written witty and humorous Poems, and in this light mood we can hope that together with lyrics poetry will have some good chances even for the future of our world.

As things are, and as fundamentally they must always be, poetry is not a career, but a mug’s game. No honest poet can ever feel quite sure of the permanent value of what he has written: He may have wasted his time and messed up his life for nothing.

T.S. Eliot

Poetry can push boundaries or employ personal experience to help understand the experience of many. It sheds light on the beautiful and the ugly and strives to understand the function of both. For these reasons and many others, poetry has been given its own holiday. World Poetry Day is held each year on March 21 to celebrate “the unique ability of poetry to capture the creative spirit of the human mind.” It was founded in 1999 by UNESCO in the hopes of promoting poetry as a way to communicate across borders and cultural differences. Since then, it has achieved just that. The event is celebrated around the world in readings and in ceremonies honoring poets of high achievement as well as in teaching the craft to aspiring writers. All in all, it is a day dedicated to poetry: an art form that has persisted for millennia and continues to enrich our understanding of the human condition to this day.

Baudelaire on poetry

“Be always drunken. Nothing else matters: that is the only question. If you would not feel the horrible burden of Time weighing on your shoulders and crushing you to the earth, be drunken continually.

“Drunken with what? With wine, with poetry, or with virtue, as you will. But be drunken.

“And if sometimes, on the stairs of a palace, or on the green side of a ditch, or in the dreary solitude of your own room, you should awaken and the drunkenness be half or wholly slipped away from you, ask of the wind, or of the wave, or of the star, or of the bird, or of the clock, of whatever flies, or sighs, or rocks, or sings, or speaks, ask what hour it is; and the wind, wave, star, bird, clock, will answer you: ‘It is the hour to be drunken! Be drunken, if you would not be martyred slaves of Time; be drunken continually! With wine, with poetry, or with virtue, as you will.’”

Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867)

Le Voyage – VIII

O Mort, vieux capitaine, il est temps ! levons l’ancre !

Ce pays nous ennuie, ô Mort ! Appareillons !

Si le ciel et la mer sont noirs comme de l’encre,

Nos coeurs que tu connais sont remplis de rayons !

Verse-nous ton poison pour qu’il nous réconforte !

Nous voulons, tant ce feu nous brûle le cerveau,

Plonger au fond du gouffre, Enfer ou Ciel, qu’importe ?

Au fond de l’Inconnu pour trouver du nouveau !

Les Fleurs du mal, Charles Baudelaire (1857)

« L’Invitation au voyage »

Mon enfant, ma sœur,

Songe à la douceur

D’aller là-bas vivre ensemble !

Aimer à loisir,

Aimer et mourir

Au pays qui te ressemble !

Les soleils mouillés

De ces ciels brouillés

Pour mon esprit ont les charmes

Si mystérieux

De tes traîtres yeux,

Brillant à travers leurs larmes.

Là, tout n’est qu’ordre et beauté,

Luxe, calme et volupté.

Des meubles luisants,

Polis par les ans,

Décoreraient notre chambre ;

Les plus rares fleurs

Mêlant leurs odeurs

Aux vagues senteurs de l’ambre,

Les riches plafonds,

Les miroirs profonds,

La splendeur orientale,

Tout y parlerait

À l’âme en secret

Sa douce langue natale.

Là, tout n’est qu’ordre et beauté,

Luxe, calme et volupté.

Vois sur ces canaux

Dormir ces vaisseaux

Dont l’humeur est vagabonde ;

C’est pour assouvir

Ton moindre désir

Qu’ils viennent du bout du monde.

– Les soleils couchants

Revêtent les champs,

Les canaux, la ville entière,

D’hyacinthe et d’or ;

Le monde s’endort

Dans une chaude lumière.

Là, tout n’est qu’ordre et beauté,

Luxe, calme et volupté.

Les Fleurs du Mal (1857)

Petit Mort Pour Rire

Va vite, léger peigneur de comètes!

Les herbes au vent seront tes cheveux;

De ton œil béant jailliront les feux

Follets, prisonniers dans les pauvres têtes…

Les fleurs de tombeau qu’on nomme Amourettes

Foisonneront plein ton rire terreux…

Et les myosotis, ces fleurs d’oubliettes…

Ne fais pas le lourd: cercueil de poètes

Pour les croque-morts sont de simples jeux.

Boîtes à violon qui sonnent le creux…

Ils te croiront mort -les bourgeois sont bêtes-

Va vite, léger peigneur de comètes!

Tristan Corbière

Risk

To laugh is to risk appearing a fool,

To weep is to risk appearing sentimental.

To reach out to another is to risk involvement,

To expose feelings is to risk exposing

your true self.

To place your ideas and dreams

before a crowd is to risk their loss.

To love is to risk not being loved in return,

To hope is to risk despair,

To try is to risk to failure.

But risks must be taken because

the greatest hazard in life is to risk nothing.

The person who risks nothing, does nothing,

has nothing is nothing.

He may avoid suffering and sorrow,

But he cannot learn, feel, change, grow or live.

Chained by his servitude he is a slave

who has forfeited all freedom.

Only a person who risks is free.”

William Arthur Ward

Spirits

Listen to Things

More often than Beings,

Hear the voice of fire,

Hear the voice of water.

Listen in the wind,

To the sighs of the bush;

This is the ancestors breathing.

Those who are dead are not ever gone;

They are in the darkness that grows lighter

And in the darkness that grows darker.

The dead are not down in the earth;

They are in the trembling of the trees

In the groaning of the woods,

In the water that runs,

In the water that sleeps,

They are in the hut, they are in the crowd:

The dead are not dead.

Listen to Things

More often than Beings,

Hear the voice of fire,

Hear the voice of water.

Listen in the wind,

To the bush that is sighing:

This is the breathing of ancestors,

Who have not gone away

Who are not under earth

Who are not really dead.

Those who are dead are not ever gone;

They are in a woman’s breast,

In the wailing of a child,

And the burning of a log,

In the moaning rock,

In the weeping grasses,

In the forest and the home.

The dead are not dead.

Listen more often

To Things than to Beings,

Hear the voice of fire,

Hear the voice of water.

Listen in the wind to

The bush that is sobbing:

This is the ancestors breathing.

Each day they renew ancient bonds,

Ancient bonds that hold fast

Binding our lot to their law,

To the will of the spirits stronger than we

To the spell of our dead who are not really dead,

Whose covenant binds us to life,

Whose authority binds to their will,

The will of the spirits that stir

In the bed of the river, on the banks of the river

The breathing of spirits

Who moan in the rocks and weep in the grasses.

Spirits inhabit

The darkness that lightens, the darkness that darkens,

The quivering tree, the murmuring wood,

The water that runs and the water that sleeps:

Spirits much stronger than we,

The breathing of the dead who are not really dead,

Of the dead who are not really gone,

Of the dead now no more in the earth.

Listen to Things

More often than Beings

Hear the voice of fire,

Hear the voice of water.

Listen to the wind,

To the bush that is sobbing:

This is the ancestors, breathing.

Birago Diop (a Senegalese poet, storyteller, veterinarian & diplomat)

On the same topic you can also read:

Alchemy of Suffering by Charles Baudelaire

A Child’s Garden of Verses by Robert L. Stevenson

The Book of Nonsense by Edward Lear

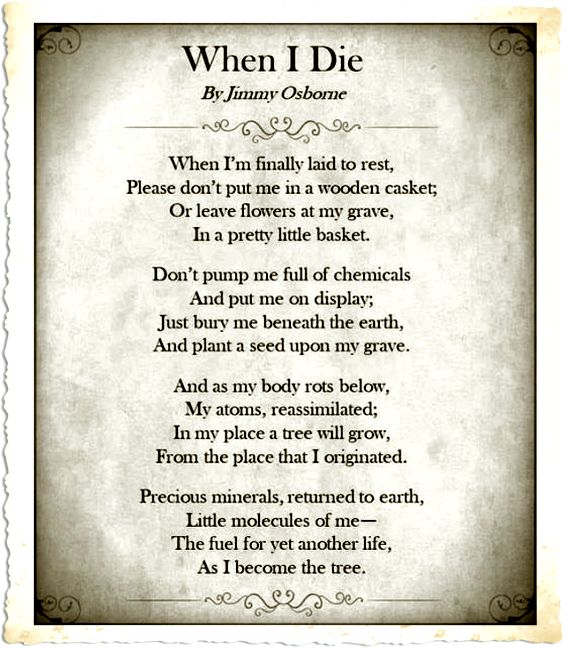

Poems and Thoughts on Halloween

Poems on Halloween, death and souls

T.S. Eliot poetic quotes and aphorisms