Houses in Great Britain, housing patterns and towns functions, sustainable architecture, houses problems and homeless, a short article to explain the situation.

If I were asked to name the chief benefit of the house, I should say: the house shelters day-dreaming, the house protects the dreamer, the house allows one to dream in peace.

Gaston Bachelard

Houses are built to live in, and not to look on: therefore let use be preferred before uniformity.

Francis Bacon

The poorest man may in his cottage bid defiance to all the forces of the Crown. It may be frail – its roof may shake – the wind may blow through it – the storm may enter – the rain may enter – but the King of England cannot enter! – all his forces dare not cross the threshold of the ruined tenement!

William Pitt Chatham

Home is the place where we are treated the best, but grumble the most.

Author Unknown

A hundred men may make an encampment, but it takes a woman to make a home.

Chinese Proverb

My home… It is my retreat and resting place from wars, I try to keep this corner as a haven against the tempest outside, as I do another corner in my soul.

Michel Eyquem De Montaigne

The house a woman creates is a Utopia. She can’t help it – can’t help trying to interest her nearest and dearest not in happiness itself but in the search for it.

Marguerite Duras

I had three chairs in my house: one for solitude, two for friendship, three for society.

Henry David Thoreau

Home is where the heart is.

Pliny The Elder

He makes his home where the living is best.

Latin Proverb

When I can no longer bear to think of the victims of broken homes, I begin to think of the victims of intact ones.

Peter De Vries

No money is better spent than what is laid out for domestic satisfaction.

Samuel Johnson

There is no place more delightful than one’s own fireplace.

Marcus T. Cicero

I want a house that has got over all its troubles; I don’t want to spend the rest of my life bringing up a young and inexperienced house.

Jerome K. Jerome

A man’s home is his wife’s castle.

Alexander Chase

We shape our dwellings, and afterwards our dwellings shape us.

Winston Churchill

Home is a name, a word, it is a strong one; stronger than magician ever spoke, or spirit ever answered to, in the strongest conjuration.

Charles Dickens

An empty house is like a stray dog or a body from which life has departed.

Samuel Butler

We can classify towns following their functions, can you make me some examples? We can have: market town: most market towns began when much of the population were farmers who needed somewhere to sell their products and where they could also buy things they needed, such as tools, seeds and anvils; Administration centre: the function of this settlement is to deal with all the work involved in running a large area, such as a county. There are many offices here such as the County Hall, police headquarters and law courts; holiday resorts: this is a place people visit for holidays.

The main function of a resort is to provide a place where people can enjoy themselves and relax; university towns: these are towns where we can find great and prestigious universities that can attract students from all over the world, usually we can find also great and efficient hospitals and scientific research centres; industrial centre: the main function of this type of settlement is the production of goods in factories. Other industrial towns may be based around a coal mine.

These settlements are usually not as old as markets towns; port town: a port is a place where goods can be brought into the country or sent to other countries by ship. Nowadays is very important to have a general plan for the development of every town, having a guide to follow to build and project the city we can promote health, safety and welfare of the people of the community. A general plan organizes and coordinates the complex relationships between urban land uses: two basic elements comprise the General Plan, the plan for land and the plan for circulation.

Patterns of housing

Over half the people in Britain live in their own houses, about a third live in property rented from the local council and one in eight live in privately-rented accommodation. The total number of dwellings is more than 22 million and houses are much more common than flats (the ratio is approximately four to one). More than 40 per cent of families live in a home built after 1945.

Although the number of houses built during the 1980s went down (especially in the public housing sector traditionally provided by local authorities) the number of people owning their own homes has more than trebled in the last thirty-five years: in 1951 only 4 million dwellings were owned by the people who lived in them; by 1988 it was more than 13 million and still rising.

Under the Conservative government many people who previously rented their homes from the local council were given the opportunity to buy them. There are tax incentives for people who buy their own homes. Buying a house is a large financial investment for many people and the majority buy their homes with a mortgage loan from a building society or bank.

The loan is repaid in monthly installments over a period of twenty years or more. Some people rent or buy accommodation through housing associations which provide a financial alternative to the mortgage system. There has also been an increase in the amount of accommodation for older people, as the number of pensioners increases.

Accommodation known as “sheltered” housing provides homes (with some degree of assistance) for elderly and disabled people. The standard of housing has improved but while most of the old slum areas in cities have been cleared, many of the large square blocks of flats which replaced them as part of the high-rise housing programme of the 1960s have been criticised as being badly designed and built. Some have been pulled down and replaced with low-rise housing.

However, because fewer houses were built and more council property was sold off, there were fewer houses available, especially for young people and those who could not afford a mortgage. House prices tend to adjust according to how much money people are earning (with occasional ‘booms’ in property prices): in Britain the cost of buying somewhere to live varies considerably according to the area.

Somewhere to live

There are many different types of housing in Britain, ranging from the traditional thatched country cottage to flats in the centre of towns. Houses are often described by the period in which they were built (for example, Georgian, Victorian, 1930s, or post-war) and whether they are terraced, semi-detached or detached. As well as preferring houses to flats, for many people a garden is also an important consideration.

Although Britain is relatively small the areas where people live vary considerably: there are new towns and inner cities, suburbs, commuter belts and the open countryside. Paying for the home you live in is the biggest single item in the budget of most families and getting on the housing “ladder” can be difficult. First-time house buyers on an average salary may have to borrow 90 or even 100 per cent of the value of the property they want to buy.

It is possible for people to borrow up to three times their annual income or sometimes even more. As prices vary, the cost of a six-bedroom farmhouse in a remote part of Scotland is about the same as a small flat in an expensive area of west London. People moving from the north to the south of Britain have to pay a lot more for the same type of house.

The average family moves once every seven years and the process of moving involves an estate agent (responsible for advertising houses for sale), a building society, bank or insurance company for the finance, and a solicitor to handle the legal aspects of the buying and selling. The size of a house or flat in Britain still tends to be measured by the number of bedrooms rather than the area in square metres. In keeping with a nation of home owners, gardening and DIY are popular spare time activities.

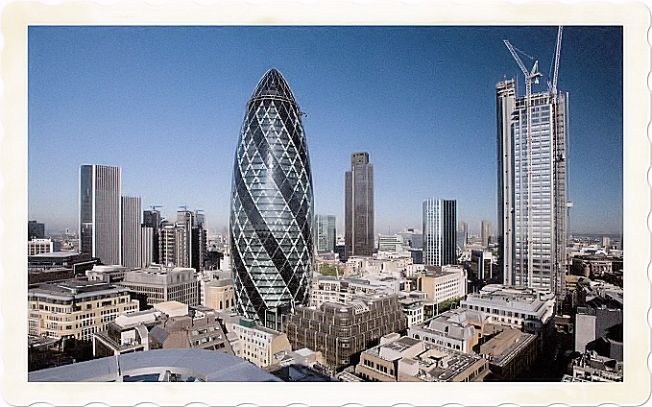

The need for housing in the south of England has produced new developments in both rural and urban areas. One example of new large-scale building is in the East End of London where fifty years ago London’s docklands were the heart of a busy international port. Today most of the ships have gone but the developers, planners, architects and builders have moved in.

A new London is being built at high speed. New roads, an airport and a docklands railway have all been built there; houses, flats and offices are being created from the old docks. While London’s skyline changes there are a number of arguments about the direction in which housing should develop. Much of the new Docklands development was designed for people to have easy access to jobs in financial institutions in the City of London, although some local residents have also benefited from the new housing and transport improvements.

The speed of the building has meant that environmental planning has not always been possible. Although some of the new buildings have won architectural awards, there has also been criticism of the new architectural styles. The demand for new homes puts pressure on both city areas and the countryside. Some of the ‘Green Belt’ of protected land which used to surround London is now being used for housing, particularly in areas which have become more affluent.

The Housing Problem

Over half the people in Britain live in their 22 million different kind of dwellings, privately owned or rented. Thanks to the Government policy, tax incentives and social and industrial development the number of people owing their own homes has more than trebled in the last thirty-five years.

A system of mortgage loans from building societies or banks, housing associations and accomodation for elderly and disabled people has largely contributed to improve the housing standard even though there are still block of flats badly designed and built and great differences in the housing market prices mainly due to the economic trend and the urban areas considered.

The housing problem is mainly due to income disparities in our social structure, even though there are other causes as well. The aim of housing production should be that of supplying good dwellings for everyone. An example of poor houses and miserable urban areas is that of slums that create bad living conditions.

Any approach to the housing problem solution requires the establishment both of a good building standard and a careful social urban development, in order to create comfortable and safe communities for every citizen, with different incomes, culture and jobs, to live in, as the English Planner E. Howard has shown us in 1898 with his ideal “garden cities” project.

The number of homeless people in Britain has doubled since 1979. Reasons for this rise include the decline in the availability of rented accommodation (nearly 1 million fewer homes than in 1980), lack of council housing due to government cuts in grants to local authorities, who are responsible for public housing, and the increases in house prices during the 1980s.

Unemployment, changes in the social security benefit regulations and the number of young people leaving home also contribute to the problem. Many local authorities have been forced to put homeless families in hotels and bed-and-breakfast accommodation because of a lack of suitable flats and houses.

While real earnings have risen faster than inflation and helped to push up house prices, debt has also increased, helping to leave some of those at the bottom of the scale without a home. One in five families in London are said to live in unsatisfactory conditions and there are an estimated 10,000 people in the capital who have to sleep rough because they have no accommodation at all.

Sustainable architecture

Sustainable architecture applies techniques of sustainable design to architecture. From the root words sus– (under) + tenere (to hold); to keep in existence; to maintain or prolong. It is related to the concept of “green building” (or “green architecture”).

The two terms, however are often used interchangeably to relate to any building designed with environmental goals in mind, often regardless of how they actually function in regard to such goals. Sustainable architecture is framed by the larger discussion of sustainability and the pressing economic and political issues of our world. In the broad context, sustainable architecture, seeks to minimize the negative environmental impact of buildings by enhancing efficiency and moderation in the use of materials, energy, and development space.

The principles of proper design on the basis of the principles of sustainable architecture may be summed up as follows: 1. Controlling the microclimate; 2. Saving energy; 3. Using renewable energy sources; 4. Using sustainable and recyclable materials; 5 Using water properly; 6. Landscaping

You can also read: