Holocaust Remembrance Day, an article with texts, images and quotes that is taken from an online exhibition and from an Italian English e-book (Free) made at school.

What happened cannot be undone, but it can be prevented from happening again.

Anne Frank

Whoever listens to a survivor of the Holocaust becomes in his turn a witness.

Elie Wiesel

I will never forget that night, the first night in the camp, which made my life a long night and seven times barred. I will never forget that smoke. I will never forget the small faces of the children whose bodies I had seen transform into curls of smoke under a silent sky. I will never forget those flames that consumed my Faith forever. I will never forget that nocturnal silence that took away from me the desire to live for eternity. I will never forget those moments that murdered my God and my soul, and my dreams, which took on the face of the desert. I will never forget all this, even if I were condemned to live as long as God himself. Never.

Elie Wiesel

Cold-blooded murder and culture are not mutually exclusive. If the Holocaust has shown us anything, it’s that a person can love poetry and still kill children.

Elie Wiesel

Take a stand. Neutrality always favors the oppressor, not the victim. Silence always encourages the torturer, never the tortured.

Elie Wiesel

A besieged city where people wander around like ghosts, students don’t go to school and teachers have nothing to teach. People don’t know where to meet: the night comes too early and the dawn too late.

Elie Wiesel

They wanted to kill the last Jew on the planet at any cost. Today we might ask: why memory, why remember, why inflict such pain? After all, it’s late for the dead but not for the living. If the torment cannot be eliminated, one can instead hope, reflect, become aware.

Elie Wiesel

The belly is still pregnant with monsters. Do you see this filthy puppet? He was there to take over the world. The peoples have won the house painter and his whole regime has gone to the bottom. But now he doesn’t rest on your laurels and don’t just think about your own business. The womb he came out of, it is still pregnant with monsters.

Bertolt Brecht

It wasn’t Hitler or Himmler who deported me, beat me, killed my family. They were the milkman, the neighbor, the shoemaker, the doctor, who was given a uniform and believed that they were the superior race.

Karel Stojka, survivor of Auschwitz

Auschwitz was a tragedy. It was a tragedy that the world turned to the other way. But as a matter of fact it is, on many occasions, what still happens today.

Carl William Brown

“It did not start with the gas chambers. It did not start with the crematoria. It did not start with the concentration and extermination camps. It didn’t start with the 6 million Jews who lost their lives. Nor did it begin with the other 10 million people who died, including Poles, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Russians, Yugoslavs, Italians, the disabled, political dissidents, prisoners of war, Jehovah’s Witnesses and homosexuals.

It began with politicians dividing people between “us” and “them”. It began with speeches of hatred and intolerance, in the streets and through the media. It began with promises and propaganda, aimed only at increasing consensus. It began with laws that distinguished people by “race” and skin color. It began with the children expelled from school, because they were children of people of another religion. It began with people deprived of their possessions, their affections, their homes, their dignity. It began with the filing of intellectuals. It began with ghettoization and deportation.

It began when people stopped caring, when people became numb, obedient and blind, with the belief that all this was “normal”. “

Primo Levi

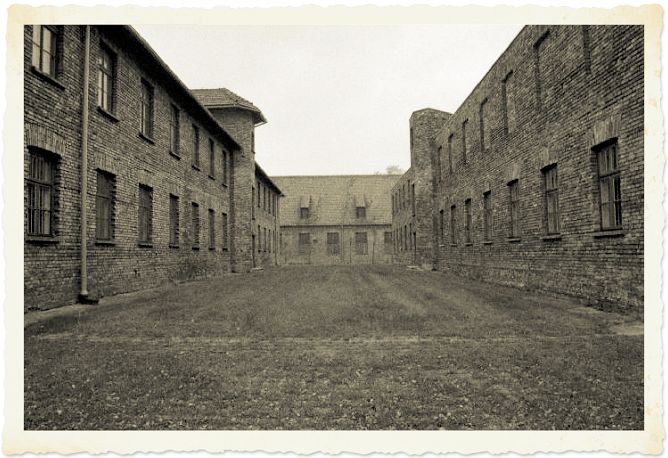

Several years ago, on the occasion of the Day of Memory, within the artistic section of the Daimon Club, I published an online exhibition, with the support and photographic material of David Cirese, a photographer in Rome, professor at the Higher Institute of Photography of the same city, and Webmaster of Netart. After a few years an e-book retraces that event.

The theme of this exhibition is of sure interest to everyone, today more than ever, starting from the world of education to get to that of politics and administration, passing through the reality of industry to arrive at that of art and literature.

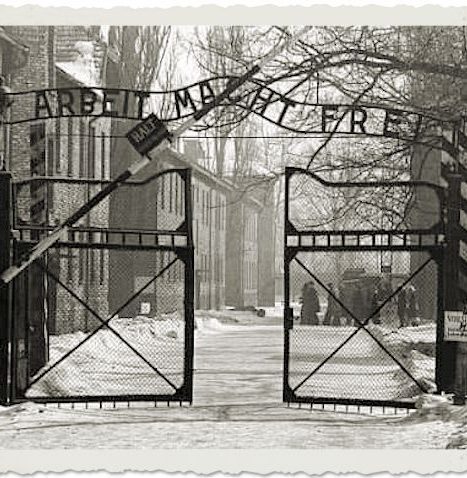

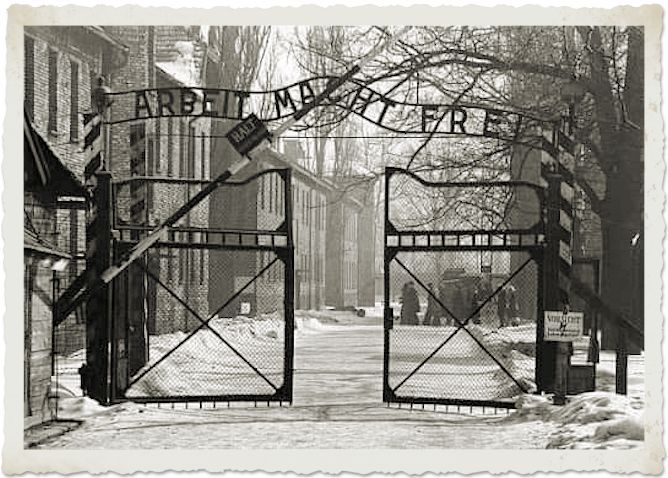

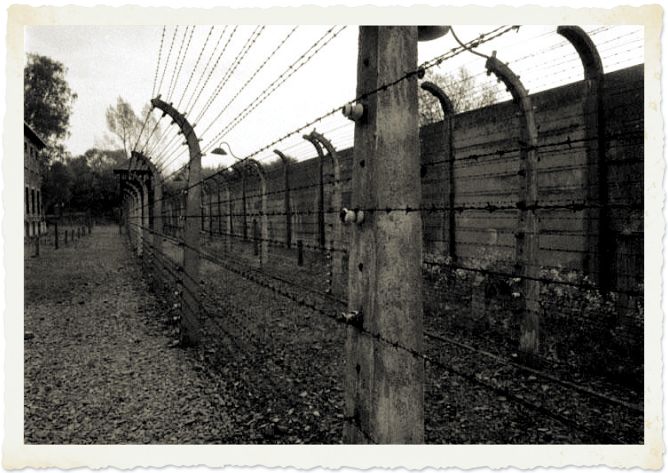

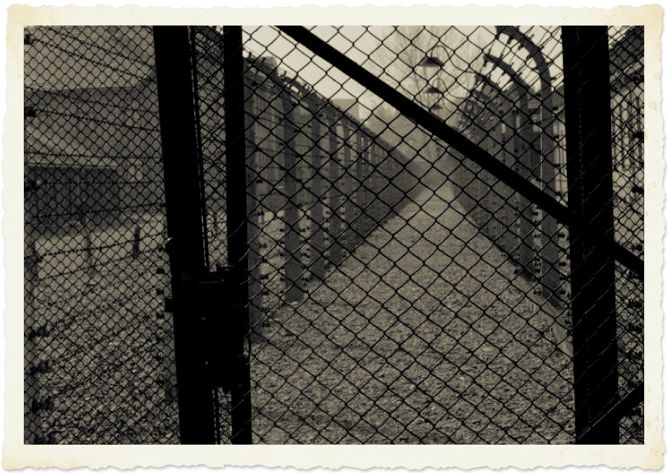

I had chosen this topic to create the first online exhibition of the club because I have always written against the power and authority of stupidity and reminding me of the passion with which my teacher of Italian in middle school explained to me the resistance and the drama of the holocaust, when I saw David Cirese’s photographs on Auschwitz on the Internet, I realized that I should have done something and thus contribute to the preservation of memory and the dissemination of sacrosanct historical information.

Anti-Semitism. Pre-World War II Persecution of German Jews

Holocaust (Greek holo, “whole”; caustos, “burned”), originally, a religious rite in which an offering was entirely consumed by fire. In current usage, holocaust refers to any widespread human disaster, but when written Holocaust, its special meaning is the almost complete destruction of the Jews in Europe by Nazi Germany.

During the 19th century, European Jewry was being emancipated, and, in most European countries, Jews achieved some equality of status with non-Jews. Nonetheless, at times Jews were vilified and harassed by anti-Semitic groups. Indeed, some anti-Semites believed that Jewry was an alien “race” not assimilable into a European culture, but they did not formulate any coherent anti-Semitic campaign. (See also POGROM.)

When the Nazi regime came to power in Germany in January 1933, it immediately began to take systematic measures against the Jews. One early decree was a definition of the term Jew. Crucial in that determination was the religion of one’s grandparents. Anyone with three or four Jewish grandparents was automatically a Jew, regardless of whether that individual was a member of the Jewish community. Half-Jews were considered Jewish only if they themselves belonged to the Jewish religion or were married to a Jewish person. All other half-Jews, and persons who had one Jewish grandparent, were styled Mischlinge (half-breeds). Jews and Mischlinge were “non-Aryans.” In Nazi doctrine, such emphasis on descent was regarded as an affirmation of “race,” but the principal purpose of these categorizations was the clear delimitation of a target for discriminatory laws and directives.

The “Aryanization” of Businesses

From 1933 to 1939, concerted efforts were made by the Nazi party, agencies of the government, banks, and business enterprises to eliminate Jews from economic life. Non-Aryans were dismissed from civil service positions, and Jewish lawyers and doctors lost their Aryan clients. Jewish firms were either liquidated and their inventory disposed of, or they were purchased for much less than their full value by companies that were not owned or operated by Jews. The contractual transfer of Jewish enterprises to new German owners was called “Aryanization.” The proceeds of any sales, as well as Jewish savings, were subjected to special property taxes. The Jewish employees of liquidated or Aryanized firms lost their jobs.

The Night of Broken Glass

The proclaimed objective of the Nazi regime was Jewish emigration. In November 1938, following the assassination of a German diplomat in Paris by a young Jew, all synagogues in Germany were set on fire, windows of Jewish shops were smashed, and thousands of Jews were arrested. This “Night of Broken Glass” (Kristallnacht) was a signal to Jews in Germany and Austria to leave as soon as possible. Several hundred thousand people were able to find refuge in other countries, but a similar number, including many who were old or poor, stayed to face an uncertain fate.

The Occupation of Poland

When World War II began in September 1939, the German army occupied the western half of Poland and thereby added almost 2 million Jews to the German power sphere. Restrictions placed on Polish Jewry were much harsher than those in Germany. The Polish Jews were forced to move into ghettos surrounded by walls and barbed wire. The ghettos were like captive city-states. Each ghetto had a Jewish council that was responsible for housing, sanitation, and production. Food and coal were to be shipped in and manufactured products sent out. The food supply allowed by the Germans, however, consisted mainly of grains and such vegetables as turnips, carrots, and beets. In the Warsaw ghetto, the official ration provided barely 1200 calories to each inhabitant. Some black-market food, smuggled into the ghettos, was sold at high prices, but unemployment and poverty were widespread. Housing was overcrowded, with six to seven people to a room, and typhus was common.

Invasion of the USSR

At the time of ghettoization in Poland, a drastic undertaking was launched farther to the east. In June 1941, German armies invaded the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), and at the same time the Reich Security Main Office – an agency of the police and the Nazi party guard, known as the SS-dispatched 3000 men in special units to newly occupied Soviet territories to kill all Jews on the spot. These mobile detachments, known as Einsatzgruppen (action squads), were soon engaged in incessant shootings. The massacres usually took place in ditches or ravines near cities and towns. Occasionally, they were witnessed by soldiers or local residents. Before long, rumors of the killings were heard in several capitals of the world.

The “Final Solution”

A month after the beginning of mobile operations in the occupied USSR, the second in command of Nazi Germany, Hermann Goring, sent a directive to the chief of the Reich Security Main Office, Reinhard Heydrich, charging him with the task of organizing a “final solution to the Jewish question” in all of German-dominated Europe. By September 1941, the Jews of Germany were forced to wear badges or armbands marked wth a yellow star. In the following months, tens of thousands were deported to ghettos in Poland and to cities wrested from the USSR. Even as that movement was under way, the stage was set for another innovation: the death camp.

Concentration Camp

Camps equipped with facilities for gassing people were erected on the soil of occupied Poland. Most prospective victims were to be deported to these killing centers from ghettos nearby. From the Warsaw ghetto alone, more than 300,000 were removed. The first transports were usually filled with women, children, or older men, who could not work; Jews capable of labor were retained in shops or plants, but they too were eventually killed. The heaviest deportations occurred in the summer and fall of 1942. The destinations of the transports were not disclosed to the Jewish communities, but reports of mass deaths eventually reached the surviving Jews, as well as the governments of the United States and Great Britain. In April 1943, the 65,000 remaining Jews of Warsaw offered resistance to German police who entered the ghetto in a final roundup. The battle was fought for three weeks.

Deportations

Throughout Europe, the deportations generated a host of political and administrative problems. In Germany itself, extensive discussions were held about the Mischlinge, and eventually they were exempted. In countries allied with Germany, such as the satellite states of Slovakia and Croatia, diplomatic negotiations were conducted to bring about deportations. The government of Vichy France, which had already extended its anti-Semitic laws, began imprisoning Jews before Germany’s request to do so.

The Italian Fascist government refused to cooperate with Nazi Germany until after Italy was occupied by German forces in September 1943, and the Hungarian government was similarly reluctant to give up its Jews until after German troops entered Hungary in March 1944. Although the Romanian government had been responsible for several large-scale massacres of Jews in the occupied USSR, Romania also declined to deliver its Jews to the Germans. In occupied Denmark, Danes from all walks of life resolved to save that country’s Jews from certain death, ferrying thousands of them in small boats to neutral Sweden.

Wherever possible, the Germans collected the belongings of the deportees. In Germany, bank accounts and the contents of apartments were confiscated, and from occupied France, Belgium, and Holland (see NETHERLANDS) furniture was shipped to Germany for distribution to bombed-out persons.

Transportation of victims to the death camps was generally by rail, and the police had to pay the German state railways a one-way third-class passenger fare for each deportee. When as many as 1000 persons were loaded on a train, a group rate that was half the normal tariff was allowed. The trains, consisting of freight cars, moved slowly on special schedules to their destinations. Often, the sick and the elderly died en route.

The Death Camps

The arrival points in Poland were Kulmhof (Chelmno), Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, Lublin (Maydanek), and Auschwitz (Oßwiécim). Kulmhof, northwest of the Lódz ghetto, was supplied with gas vans, and its death toll was 150,000. Belzec had carbon monoxide gas chambers in which 600,000 Jews, mostly from the populous Galician area, were killed. Sobibor’s gas chambers accounted for 250,000 dead and Treblinka’s for 700,000 to 800,000. At Lublin, some 50,000 were gassed or shot; in Auschwitz, the Jewish dead totaled more than 1 million.

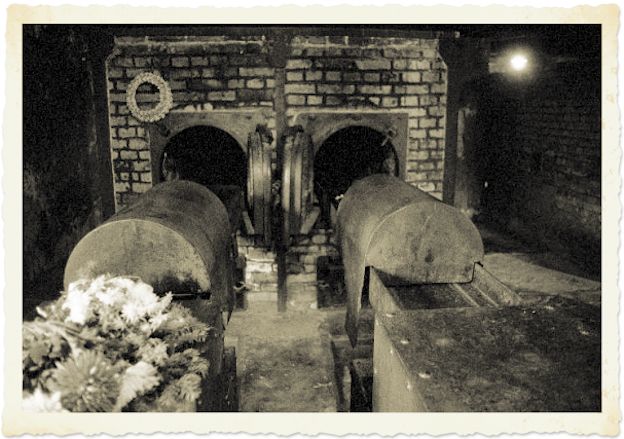

Auschwitz, near Kraków, was the largest death camp. Unlike the others, it used quick-working hydrogen cyanide for the gassings. The victims of Auschwitz came from all over Europe: Norway, France, the Low Countries, Italy, Germany, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, Yugoslavia, and Greece. A large inmate population, Jewish and non-Jewish, was employed by industry; some prisoners were subjected to medical experiments, particularly sterilizations. Although only Jews and Gypsies were gassed routinely, several hundred thousand other Auschwitz inmates died from starvation, disease, or shooting. To erase the traces of destruction, large crematories were constructed so that the bodies of the gassed could be incinerated. In 1944 the camp was photographed by Allied reconnaissance aircraft in search of industrial targets; its factories, but not its gas chambers, were bombed.

Results of the Holocaust

When the war ended, millions of Jews, Slavs, Gypsies, homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Communists, and others targeted by the Nazis, had died in the Holocaust. The Jewish dead numbered more than 5 million: about 3 million in killing centers and other camps, 1.4 million in shooting operations, and more than 600,000 in ghettos. (Traditional estimates are closer to 6 million.) Heavy pressure was placed on the victorious powers to establish a permanent haven in Palestine for Jewish survivors. The establishment of Israel three years after Germany’s defeat was thus an aftereffect of the Holocaust.

Raul Hilberg

Concentration Camp

A prisonlike place created to confine selected groups of people, usually for political reasons. It differs from a regular prison in three ways: (1) men, women, and children are confined without normal judicial trials; (2) the period of confinement is indeterminate; and (3) camp authorities exercise unlimited, arbitrary power. Although many kinds of facilities have served as concentration camps, they usually consist of barracks, huts, or tents, surrounded by watchtowers and barbed wire. Concentration camps are also known by various other names such as corrective labor camps, relocation centers, and reception centers.

Western Camps

Modern concentration camps appeared at the end of the 19th century. The Spaniards used them in Cuba during the Spanish-American War (1898), and the British established them for thousands of women and children during the Boer War (1899-1902) in South Africa. In the West camps have been created several times during periods of war and national emergency. In France the government committed Spanish Republican refugees to reception centers in 1938 and added Jewish and other anti-Nazi refugees the following year. In Great Britain the government used Defense Regulation 18B in 1939 to send potentially disloyal citizens and refugees from enemy countries to internment camps. In the U.S., Executive Orders 9066 and 9102, later upheld by the Supreme Court, empowered the military to transport 70,000 U.S. citizens of Japanese descent and 42,000 Japanese resident aliens from the West Coast to relocation centers in the interior.

Soviet Camps

In Russia the Bolsheviks established concentration camps for suspected counterrevolutionaries in 1918. During the 1920s, “class enemies” and criminals were confined in the Northern Special Purpose Camps on the Solovetskiye Islands in the White Sea and near Arkhangelsk on the mainland. In the 1930s and ’40s, a system of corrective labor camps covered most of the Soviet Union and received millions of prisoners in successive waves of mass arrests: independent farmers (kulaks); victims of the great purges; populations deported from the Polish and Baltic territories annexed in 1939; groups such as the Volga Germans considered potentially disloyal during World War II; Axis prisoners of war; and Russians returning from German captivity. After the death of Joseph Stalin (1953), when many inmates received amnesty and were released, the camps continued on a smaller scale.

In 1919 the Russian secret police, then known as the Cheka and later under successive other names (see KGB), was empowered to arrest “class enemies.” Commitment to a camp usually followed a hearing by the Judicial Collegium of the secret police, using elastic paragraphs of the criminal code to sentence defendants who had neither the right to be present nor to defend themselves. During the 1920s the camps were administered by various agencies, including the People’s Commissariat of Justice. In 1930 control over all camps was assumed by the Chief Administration of Camps (Glavnoye uptavlenie lagetov, or GULAG) in the People’s Commissariat of the Interior (Natodny kommissariat vnutrennikh dyel, or NKVD).

Millions of camp inmates worked as forced laborers on numerous projects essential to the Soviet economy. Some of these, such as the White Sea-Baltic Canal and the Moscow-Volga Canal, claimed innumerable lives. Other projects – such as the coal mines and oil wells near Vorkuta and the gold mines on the Kolyma River—exploited the mineral wealth in the Soviet Arctic. Eventually, five major camp systems existed: (1) the Yagry near Arkhangelsk; (2) the Pechora, including Kotlas and Vorkuta; (3) the Karaganda in Kazakhstan; (4) the Tayshet-Komsomolsk in the Lake Baykal-Amur River region; and (5) the Dalstroy in the Magadan-Kolyma region.

Nazi Camps

In Germany, the Nazis established concentration camps almost immediately after assuming power on January 30, 1933. A decree in February removed the constitutional protection against arbitrary arrest. The security police had the authority to arrest anyone and to commit that person to a camp for an indefinite period. The political police, known as the Gestapo, imposed “protective custody” on a wide variety of political opponents: Communists, socialists, religious dissenters, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Jews. The criminal police, known as the Kripo, imposed “preventive arrest” on professional criminals and numerous groups of so-called asocials: Gypsies, homosexuals, prostitutes, and shirkers.

The SS (Schutzstaffel, or protective units) operated the camps with brutal military discipline. During the 1930s six major camps were established: Dachau, Sachsenhausen, Buchenwald, Flossenbürg, Mauthausen, and, for women, Ravensbrück. In 1939 these camps held about 25,000 prisoners. During World War II the camps increased in size and number. Important new ones included Auschwitz-Birkenau, Natzweiler, Neuengamme, Gross Rosen, Stutthof, Lublin-Maidanek, Hinzert, Vught, Dora, and Bergen-Belsen. Millions of prisoners entered these camps from every occupied country of Europe: Jews, partisans, Soviet prisoners of war, and impressed foreign laborers.

Early in 1942 the SS Central Office for Economy and Administration (Wirtschafts-Verwaltungehauptamt, or WVHA) assumed operational control of the concentration camps, and inmates were exploited as forced laborers in industrial production. In addition to the central camps, the WVHA operated hundreds of subsidiary camps, and local offices of the security police in the occupied territories maintained large numbers of forced labor camps. Inmates were worked to death in industries such as the I. G. Farben chemical works and the V-2 rocket factories. Those no longer able to work were killed by gassing, shooting, or fatal injections. Inmates were also used for “medical experiments.” Early in 1945 the camp population exceeded 700,000.

During World War II the Nazis also established extermination centers to kill entire populations. There the SS systematically gassed millions of Jews and thousands of Gypsies and Soviet prisoners of war. Two extermination centers operated in concentration camps under the authority of the WVHA: Auschwitz-Birkenau and Lublin-Maidanek. Five operated in camps established by regional SS and police leaders: Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka in eastern Poland; Kulmhof (Chelmno) in western Poland; and Semlin outside Belgrade, in Serbia. More than 4 million persons, the majority of whom were Jews, perished in the Nazi camps. (Millions of Jews were also exterminated outside the camps.)

Other Camps

Since World War II numerous repressive regimes have established concentration camps. Thus, Communist regimes in Asia have used reeducation camps to detain vast numbers of men, women, and children. In the 1950s the British established emergency detention camps in Kenya; in the 1960s the government of Indonesia placed opponents in island camps; and in the 1970s the military regime in Argentina operated secret detention camps.

Henry Friedlander

At the following links you can see the original work:

Daimon Art Exhibition with David Cirese photographs on Auschwitz

Giornata della memoria, an article with almost all the photos in Italian

The E-book with all the images and with texts, included a students survey