Guy Fawkes Day, also known as Guy Fawkes Night or Bonfire Night and Firework Night, is an annual commemoration observed on 5 November, primarily in Great Britain.This article talks about its origin, celebrations, tradition and customs. Guy Fawkes Day is not a public holiday. Businesses have normal opening hours. A firework display to celebrate Guy Fawkes Night, also known as Bonfire Night.

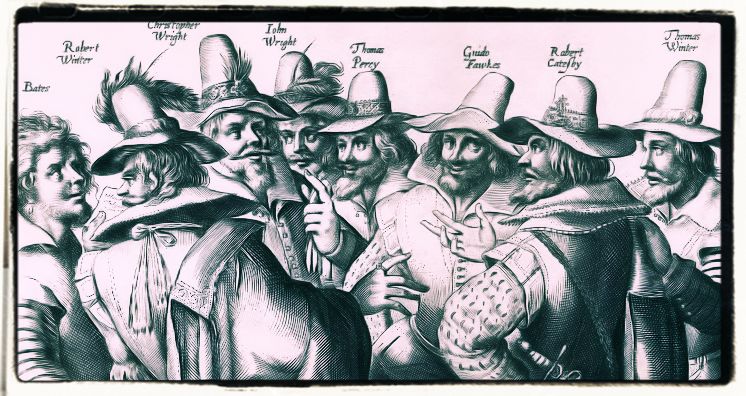

Its history begins with the events of 5 November 1605, when Guy Fawkes and some friends, a group of provincial English Catholics, tried to blow up the Houses of Parliament with gunpowder and assasinate the Protestant King James I of England and replace him with a Catholic head of state; like many people (in the past as well as now!) they didn’t like the government.

The attempt failed and Guy Fawkes was caught and arrested while guarding explosives the plotters had placed beneath the House of Lords. Celebrating the fact that King James I had survived the attempt on his life, people lit bonfires around London, and months later the introduction of the Observance of 5th November Act enforced an annual public day of thanksgiving for the plot’s failure, in fact the parliament had said that every year on November 5th people should remember the Gunpowder Plot, that is the day when Members of Parliament were saved from a horrible death.

Within a few decades Gunpowder Treason Day, as it was known, became the predominant English state commemoration, but as it carried strong Protestant religious overtones it also became a focus for anti-Catholic sentiment. Puritans delivered sermons regarding the perceived dangers of popery, while during increasingly raucous celebrations common folk burnt effigies of popular hate-figures, such as the pope. Towards the end of the 18th century reports appear of children begging for money with effigies of Guy Fawkes and 5 November gradually became known as Guy Fawkes Day.

Towns such as Lewes and Guildford were in the 19th century scenes of increasingly violent class-based confrontations, fostering traditions those towns celebrate still, albeit peaceably. In the 1850s changing attitudes resulted in the toning down of much of the day’s anti-Catholic rhetoric, and the Observance of 5th November Act was repealed in 1859. Eventually the violence was dealt with, and by the 20th century Guy Fawkes Day had become an enjoyable social commemoration, although lacking much of its original focus. The present-day Guy Fawkes Night is usually celebrated at large organised events, centred on a bonfire and extravagant firework displays.

Settlers exported Guy Fawkes Night to overseas colonies, including some in North America, where it was known as Pope Day. Those festivities died out with the onset of the American Revolution. Claims that Guy Fawkes Night was a Protestant replacement for older customs like Samhain are disputed, although another old celebration, Halloween, has lately increased in popularity, and according to some writers, may threaten the continued observance of 5 November.

Little is known about the earliest celebrations. In settlements such as Carlisle, Norwich and Nottingham, corporations provided music and artillery salutes. Canterbury celebrated 5 November 1607 with 106 pounds of gunpowder and 14 pounds of match, and three years later food and drink was provided for local dignitaries, as well as music, explosions and a parade by the local militia. Even less is known of how the occasion was first commemorated by the general public, although records indicate that in the Protestant stronghold of Dorchester a sermon was read, the church bells rung, and bonfires and fireworks lit.

Organised entertainments also became popular in the late 19th century, and 20th-century pyrotechnic manufacturers renamed Guy Fawkes Day as Firework Night. Sales of fireworks dwindled somewhat during the First World War, but resumed in the following peace. At the start of the Second World War celebrations were again suspended, resuming in November 1945. For many families, Guy Fawkes Night became a domestic celebration, and children often congregated on street corners, or standing outside railway stations accompanied by their own figures effigy of Guy Fawkes made of soks and straw and dressed in old clothes. Collecting money was a popular reason for their creation, the children taking their effigy from door to door, or displaying it on street corners, while saying “Penny for the guy”.

However they were mainly built to go on the bonfire, itself sometimes comprising wood stolen from other pyres; “an acceptable convention” that helped bolster another November tradition, Mischief Night. Rival gangs competed to see who could build the largest, sometimes even burning the wood collected by their opponents; in 1954 the Yorkshire Post reported on fires late in September, a situation that forced the authorities to remove latent piles of wood for safety reasons.

Lately, however, the custom of begging for a “penny for the Guy” has almost completely disappeared. In contrast, some older customs still survive; in Ottery St Mary men chase each other through the streets with lit tar barrels, and since 1679 Lewes has been the setting of some of England’s most extravagant 5 November celebrations, the Lewes Bonfire. Generally, modern 5 November celebrations are run by local charities and other organisations, with paid admission and controlled access, anyway Guy Fawkes’ Day is finally declining, having lost its connection with politics and religion. But we have heard that many times before.

The Fifth of November

Remember, remember!

The fifth of November,

The Gunpowder treason and plot;

I know of no reason

Why the Gunpowder treason

Should ever be forgot!

Guy Fawkes and his companions

Did the scheme contrive,

To blow the King and Parliament

All up alive.

Threescore barrels, laid below,

To prove old England’s overthrow.

But, by God’s providence, him they catch,

With a dark lantern, lighting a match!

A stick and a stake

For King James’s sake!

If you won’t give me one,

I’ll take two,

The better for me,

And the worse for you.

A rope, a rope, to hang the Pope,

A penn’orth of cheese to choke him,

A pint of beer to wash it down,

And a jolly good fire to burn him.

Holloa, boys! holloa, boys! make the bells ring!

Holloa, boys! holloa boys! God save the King!

Hip, hip, hooor-r-r-ray!

English Folk Verse (c.1870)

Perhaps most widely known in America from its use in the movie V for Vendetta, versions of the above poem have been wide spread in England for centuries. They celebrate the foiling of (Catholic) Guy Fawkes’s attempt to blow up (Protestant controlled) England’s House of Parliament on November 5th, 1605. Known variously as Guy Fawkes Day, Gunpowder Treason Day, and Fireworks Night, the November 5th celebrations in some time periods included the burning of the Pope or Guy Fawkes in effigy. This traditional verse exists in a large number of variations and the above version has been constructed to give a flavor for the major themes that appear in them. Several of the reference books on the subject cite even earlier sources.

Guy Fawkes also inspired the mask that V wears in the movie V for Vendetta, a dystopian political thriller directed by James McTeigue and written by The Wachowski Brothers, based on the 1988 DC/Vertigo Comics that were initially a British graphic novel written by Alan Moore and illustrated by David Lloyd published in black and white as an ongoing serial in the short-lived UK anthology Warrior, and only after morphed into a ten-issue limited series published by DC Comics.

In modern society in general, this mask has become a symbol of anarchism, revolution, and civil disobedience, for example, demonstrators in Egypt and at Occupy Wall Street in New York City wore the iconic mask to show their disapproval of the government.

Within the graphic novel, the mask is a powerful symbol: it communicates the wearer’s allegiance to the spirit of Guy Fawkes, the man who tried and failed to blow up the Houses of Parliament in the 16th century and his opposition to the Norsefire government that controls England. One important element of the mask’s power as a symbol is its anonymity: anyone can wear the mask and embody the spirit of rebellion.

We see this first-hand in the graphic novel, as in the final chapters, Evey Hammond dons V’s mask and “becomes” V. In the end, then, the Guy Fawkes mask represents symbols at their most powerful: they can transform individual, flawed people into something more powerful and create movements.

You can also read: