English language idioms, the importance, evolution and linguistic meaning of this fundamental aspect of the American English language for every learners.

We often read and hear the phrase “language is a living thing”, but most of us do not stop to think about how and why this is true. Living things grow and change, and so does language. It is the Diachronic function of the language, diachronic literally means across-time, and it describes any work which maps the shifts and fractures and mutations of languages over the centuries. (Diachronic linguistics is the study of a language through different periods in history. Diachronic linguistics is one of the two main temporal dimensions of language study identified by Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure in his Course in General Linguistics (1916). The other is synchronic linguistics. The terms diachrony and synchrony refer, respectively, to an evolutionary phase of language and to a language state. “In reality,” says Théophile Obenga, “diachronic and synchronic linguistics interlock” (“Genetic Linguistic Connections of Ancient Egypt and the Rest of Africa,” 1996). One can readily recognize differences between Shakespeare’s English and the English of modern authors, but present-day English is also growing and changing, and these tendencies are not so easy to recognize. Since the general tendencies of present-day English are towards more idiomatic usage.

Colloquialisms are familiar words and idioms used in informal speech and writing, but not considered explicit or formal enough for polite conversation or business correspondence. Unlike slang, however, colloquialisms are used and understood by nearly everyone in the United States. The use of slang conveys the suggestion that the speaker and the listener enjoy a special “fraternity,” but the use of colloquialisms emphasizes only the informality and familiarity of a general social situation. Almost all idiomatic expressions, for example, could be labeled colloquial. Colloquially, one might say: Friend, you talk plain and hit the nail right on the head. Cant is the conversational, familiar idiom used and generally understood only by members of a specific occupation, trade, profession, sect, class, age group, interest group, or other sub-group of our culture. Jargon is the technical or even secret vocabulary of such a sub-group; jargon is “shop talk.” Argot is both the cant and the jargon of any professional criminal group.

Some people think that idiomatic language is more informal and, therefore, common only in spoken English. This is not true. Idiomatic language is as fundamental to English as tenses or prepositions. If you listen to people speaking, or if you read a novel or a newspaper, you will meet idiomatic English in all these situations. Idioms certainly show the speakers how the language is developing. Idioms are not a separate part of the language which one can choose either to use or to omit, but they form an essential part of the general vocabulary of English. A description of how the vocabulary of the language is growing and changing will help to place idioms in perspective, and they show some changing attitudes towards language.

One does not need to be a language expert to realise that the vocabulary of a language grows continually with new developments in knowledge. New ideas must have new labels to name them. Without new labels, communication of these new ideas to others would be impossible. Most such words come from the English of special subjects such as science and technology, psychology, sociology, politics and economics. Words which already exist can also take on a particular meaning in a particular situation. For example, to lock someone out usually means “to lock a door in order to prevent someone from entering”. However, the verb has a special meaning in the context of industrial relations. It means that the employers refuse to let the workers return to their place of work until they stop protesting. The noun a lock-out is also used in this special context, and it is, therefore, a new word in the language. Similar words are to sit in, a sit-in and to walk out, a walk-out, where the verbs take on a new meaning in the context of industrial strike and protest and where , the nouns are only used in this context, thus becoming new words.

Not only can words which already exist express new ideas and thus help a language to grow; also, new ideas can be expressed by the combination of two or three existing words. Here is an example of this: the words wage and to freeze are well known, but the idea of a wage freeze came into the language only a few years ago. To freeze wages is another expression from British politics and economics and means “to stop increases in wages”. The same idea is found in to freeze prices and a price-freeze. A new word can be formed by changing a verbal phrase into a noun (as in a lock-out), or by changing a noun into a verb. Both these changes are very popular in American English (AE) and British English (BE) quickly borrows new word formations from AE. Here are some nouns formed from verbal phrases: a stop-over, a check-up, a walk-over, a hand-out, a set-up, all common especially in informal style. Here are some verbs formed from nouns: to pilot (a plane), to captain (a team), to radio (a message), to service (a motorcar), to air freight (a parcel), to Xerox (a document), to pressure (somebody). It is easy to give words new grammatical functions because English is flexible. When the function is changed, it is not necessary to change the form.

Not only nouns, but also adjectives are made into verbs to show a process, as in to soundproof, to skidproof, to streamline. All these changes in the function of words have one purpose, that is, to make the form of words used shorter and more direct. They are short-cuts in language. These short forms are quicker and more convenient and for this reason they are becoming more and more popular. There are other short-cuts which BE has borrowed from AE. Verbs can also be made from the root of a noun, e g to housekeep from the noun housekeeper, to barkeep from barkeeper, to babysit from babysitter. To house-sit is a new word which has been copied from to babysit, because it includes the same idea, namely, “to look after someone’s house while he is away”. Another short-cut joins words together in order to form one adjective instead of a long phrase, e g a round-the-clock service, instead of “a service which is offered around the clock”. (i.e. 24 hours).

New words can be made by adding endings such as -ise or -isation to adjectives or nouns. This is especially popular in the language of newspapers. Here are some examples: to decimalise instead of the long phrase “to change into the decimal system”, to departmentalise instead of “to organise into different depart-ments” and containerisation instead of “the process of putting things into containers”. Prefixes such as mini-, maxi-, super-, uni-, non-, extra- are put in front of words (mainly nouns and adjectives) to indicate the quantity or quality of something in the shortest possible way. Here are some examples: supergrade petrol (the best quality), uni-sex (in fashion, the same design in clothes for men and women), a non-stick frying-pan, non-skid tyres, mini-skirt, extra-mild cigarettes. New words can be made by mixing two words that already exist, i.e. by combining part of one word with part of another. A well-known example is smog (smoke + fog). Others are brunch (breakfast + lunch), newscast (news + broadcast) and motel (motorist + hotel). AE uses more of these words than BE. Here are some from AE: laundromat (laundry + automat), cablegram (cable + telegram) and medicare (medical + care). Here is one from the world of economics : stagflation (stagnation + inflation).

Some ideas are small and very particular. Other ideas are big. They bring lots of related ideas to mind. For example, we all know what a ‘coin’ is. It is a small piece of metal which we use to pay for things. It is a part of a much bigger idea – ‘money’. When we think of money we think of saving it, earning it, wasting it, spending it, being generous with it, being mean with it. Money is a bigger idea than coins or banknotes. When we use the common metaphor – time is money – we know what we mean. Many of the words we use with money, we also use with time: We have time to spare. We waste time. We spend time doing something. We run out of time. We save time. The difference between idioms and metaphors is that metaphors use implied comparisons to create meaning whereas idioms are instinctively understood by the language user without having to use implied comparison to deduce the meaning. In fact, the original meaning is often not logically deducible. That’s tough, so let’s break it down: Metaphors compare one thing to another thing by saying something is something else.

You can decode them by analyzing the similarities between the two things being implicitly compared. Idioms are expressions that are understood by language users without the need to decode them because those idioms have become commonplace phrases in the language. If a metaphor becomes commonplace enough in a language, it may become idiomatic. The metaphor “she is an early bird” compares the lady to a bird but phrases it as if they are literally the same. The bird in the metaphor always wakes up early in the morning. So, we can logically deduce that this metaphor is highlighting that the woman wakes up early, too. The idiom “it’s raining cats and dogs” means that the rain outside is very heavy. There is no clear logical connection we can make between cats and dogs falling from the sky and heavy rain.

Educated writers and readers of English are becoming more flexible and tolerant about what is considered to be correct or acceptable usage. Some deviations from the grammatical rules of the past are now accepted not only in spoken but also in written English. Such changes of attitude can be observed in several parts of grammar, including case, number, tense and the position of prepositions at the end of a phrase or sentence. A few examples will make this clear. Who shall I ask? now appears in written English instead of Whom shall I ask? (case). Neither of them are coming instead of Neither of them is coming (number). I never heard of her before instead of I have never heard of her before (tense). Prepositions appear now quite regularly at the end of a sentence in written English, where previously this was only common in spoken English and was considered bad style when written. Examples of all the above can easily be found even in newspapers which have a reputation for writing good and correct English. The attitude of users of the language towards style is also becoming more flexible. Words which were considered to be slang in the past may be more acceptable in present-day English; they may now be considered to be colloquial or informal.

The expression to be browned off with somebody was in the past a slang expression for “to be bored with or irritated by somebody”. Since the slang expression of the same meaning to be cheesed off with somebody came into the language, browned off has generally risen in status and is now considered by most people to be informal and not slang. There are several other cases where a new expression has replaced an already existing one, giving the existing expression a rise in status from slang to informal. This is also partly due to the spread in the use of taboo words (or swear-words), which much more freely now re-place words (like damn and bloody) which were in the past considered to be bad language. The taboo words are now bad language and the other words do not give so much offense as in the past. Both of these sets of words, however, should be avoided by the learner until his mastery of the language is so complete that he knows exactly when, where and how to use such words.

An important fact which must be stressed is that idioms are not only colloquial expressions, as many people believe. They can appear in formal style and in slang. They can appear in poetry or in the language of Shakespeare and the Bible. What, then, is an idiom? We can say that an idiom is a number of words which, taken together, mean something different from the individual words of the idiom when they stand alone. The way in which the words are put together is often odd, illogical or even grammatically incorrect. These are the special features of some idioms. Other idioms are completely regular and logical in their grammar and vocabulary. Because of the special features of some idioms, we have to learn the idiom as a whole and we often cannot change any part of it (except perhaps, only the tense of the verb). English is very rich in idiomatic expressions. In fact, it is difficult to speak or write English without using idioms. An English native speaker is very often not aware that he is using an idiom; perhaps he does not even realise that an idiom which he uses is grammatically incorrect. A non-native learner makes the correct use of idiomatic English one of his main aims, and the fact that some idioms are illogical or grammatically incorrect causes him difficulty. Only careful study and exact learning will help. It cannot be explained why a particular idiom has developed an unusual arrangement or choice of words. The idiom has been fixed by long usage as is sometimes seen from the vocabulary.

The idiom to buy a pig in a poke means “to buy something which one has not inspected previously and which is worth less than one paid for it”. The word poke is an old word meaning sack. Poke only appears in present-day English with this meaning in this idiom. Therefore, it is clear that the idiom has continued to be used long after the individual word. There are many different sources of idioms. As will be made clear later, the most important thing about idioms is their meaning. This is why a native speaker does not notice that an idiom is incorrect grammatically. If the source of an idiom is known, it is sometimes easier to imagine its meaning. Many idiomatic phrases come from the every-day life of Englishmen, from home life, e.g. to be born with a silver spoon in one’s mouth, to make a clean sweep of something, to hit the nail on the head. There are many which have to do with food and cooking, e.g. to eat humble pie, out of the frying-pan into the fire, to be in the soup. Agricultural life has given rise to to go to seed, to put one’s hand to the plough, to lead someone up the garden path. Nautical life and military life are the source of when one’s ship comes home, to be in the same boat as someone, to be in deep waters, to sail under false colors, to cross swords with someone, to fight a pitched battle, to fight a losing winning battle.

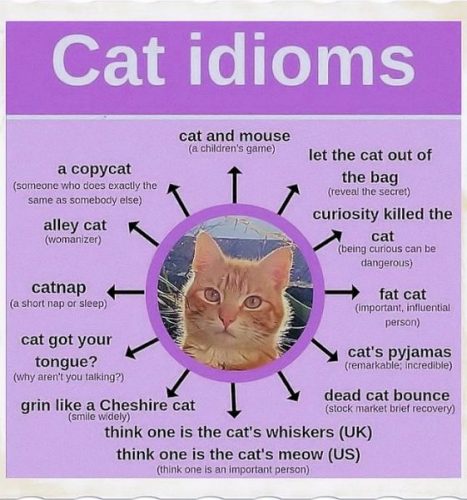

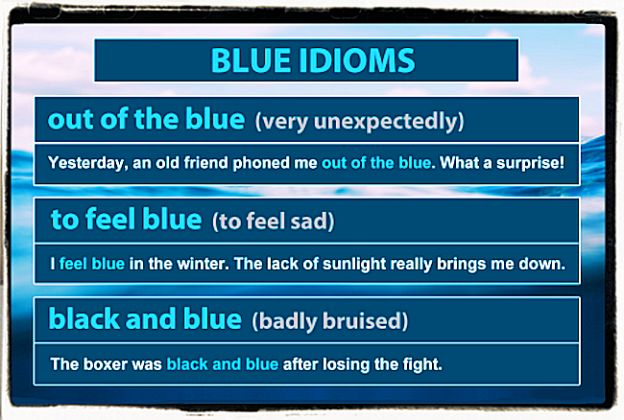

Many idioms include parts of the body, animals, and colours. The Bible gives us to kill the fatted calf, to turn the other cheek, the apple of one’s eye. Idioms take many different forms or structures. They can be very short or rather long. A large number of idioms consist of some combination of noun and adjective, e.g. cold war, a dark horse, French leave, forty winks, a snake in the grass. Some idioms are much longer: to fish in troubled waters, to take the bull by the horns, to cut one’s coat according to one’s cloth. An idiom can have a regular structure, an irregular or even a grammatically incorrect structure. The idiom I am good friends with him is irregular or illogical in its grammatical structure. I is singular, why then is the correct form in this case not I am a good friend with him? This form is impossible although it is more logical; one would have to say I am a good friend of his. A native speaker is not consciously aware of this inconsistency. This is, therefore, an example of the kind of idiom where the form is irregular but the meaning clear. A second kind has a regular form but a meaning that is not clear. To have a bee in one’s bonnet has a regular form, but its meaning is not obvious. It means, in fact, that one is obsessed by an idea, but how can we know this if we have not learnt it as an idiom ? There is a third group, in which both form and meaning are irregular.

To be at large: the form Verb +Preposition + Adjective without noun is strange, and we have no idea what it means, either! If we talk about a prisoner who is still at large, it means that he is still free. Here are similar examples: to go through thick and thin, to be at daggers drawn, to be in the swim. We find, in fact, that most idioms belong to the second group, where the form is regular, but the meaning is unclear. However, even in this group, some idioms are clearer than others, that is, some are easier to guess than others. Take the example to give someone the green light. We can guess the meaning even though we! may never have heard it before. If we associate “the green light” with traffic lights where green means “Go!”, we can imagine that the idiom means “to give someone permission to start something”.

Other idioms can be guessed if we hear them in context, that is, when we know how they are used in a particular situation. For example, let us take the idiom to be at the top of the tree. If we hear the sentence “John is at the top of the tree now”, we are not sure what this is saying about John. Perhaps it means that he is in a dangerous position or that he is hiding. But if we hear the phrase in context, the meaning becomes clear to us: Ten years ago John joined the company, and now he’s the general manager! Yes, he’s really at the top of the tree! The idiom means ‘to be at the top of one’s profession, to be successful’.

However, some idioms are too difficult to guess correctly be-cause they have no association with the original meaning of the individual words. Here are some examples : to tell someone where to get off, to bring the house down, to take it out on someone. The learner will have great difficulty here unless he has heard the idioms before. Even when they are used in context, it is not easy to detect the meaning exactly. We shall take a closer look at the first of these examples. To get off usually appears together with bus or bicycle, as in this sentence: Mary didn’t know her way round town, so Jane took her to the bus stop and then told her where to get off. But in its idiomatic sense to tell someone where to get off means ‘to tell someone rudely and openly what you think of him’ as in this context: Jane had had enough of Mary’s stupid and critical remarks, so she finally told her where to get off. For a foreign learner, this idiomatic meaning is not even exactly clear in context. It was said earlier that we have to learn an idiom as a whole be-cause we often cannot change any part of it. A question which the learner may ask is: “How do I know which parts of which idioms can be changed?” The idioms which cannot be changed at all are called fixed idioms. Some idioms are fixed in some of their parts but not in others. Some idioms allow only limited changes in the parts which are not fixed.

We have now talked about several aspects of idioms : where they come from, their form, their meaning, if and how we can vary them. We shall now look at the reasons for the difficulties which foreign learners experience when they try to use idioms. One of the main difficulties is that the learner does not know in which situations it is correct to use an idiom. He does not know the level of style, that is, whether an idiom can be used in a formal or in an informal situation. Help is given in this book with the markings formal and informal. Unmarked idioms can be used in any situation. Choice of words depends on the person one is speaking to and on the situation or place at the time. If the person is a friend and the situation is private, we may use informal or even slang expressions. In a formal situation, when we do not know the person we are speaking to very well or the occasion is public, we choose words much more carefully. It would be wrong to choose an informal expression in some rather formal situation and bad manners to choose a slang expression. This means that we can express the same information or idea in more than one way using a different level. Here is an example. If one arrives late when meeting a friend, a typical informal way of apologizing would be: “Sorry I’m late! but I got badly held up.” However, if one came too late to a meeting with strangers or a business meeting, another choice of expression for the apology would be appropriate, perhaps “I do apologize for being late. I’m afraid my train was delayed.”

The expressions marked formal are found in written more than in spoken English and are used to show a distant relationship between the speakers. Such expressions would be used for example when making a formal speech to a large audience. Expressions marked informal are used in every-day spoken English and in personal letters. (Slang expressions are used in very informal situations between good friends. Learners should not make frequent use o slang expressions as they usually – but unexpectedly – become out-of-date and sound strange. It is advisable to concentrate on the expressions which are marked informal and on the unmarked expressions which are neutral in style and can be used in any situation.

Another major difficulty is that the learner does not know if an idiom is natural or appropriate in a certain situation. This can only be learnt by careful listening to native speakers or careful reading of English texts which contain idioms. Last but not least remember that most English idioms are used in English speech just like any other phrase, clause or sentence, i.e. the word that is given the main stress (or accent) is the last noun (not pronoun), verb (not auxiliary verb), adjective or adverb in the phrase, clause or sentence. For example, in the idioms on the face of it, to take the cake and neither here nor there, the words face, cake and there carry the strong stress. However, in some idioms the word that carries the strong stress is not the last “main” word in that idiom.

To find out more about these aspects of the language you can also read:

English idioms organizer (PDF)