Dickens literary London a guided tour through the magic city of the Victorian era with the places made famous by Dickens himself, his novels and his characters.

I landed in London on a wintry autumn evening. It was dark and raining, and I saw more fog and mud in a minute than I had seen in a year. I walked from the Custom House to the Monument before I found a coach; and although the very house-fronts, looking on the swollen gutters, were like old friends to me, I could not but admit that they were very dingy friends.

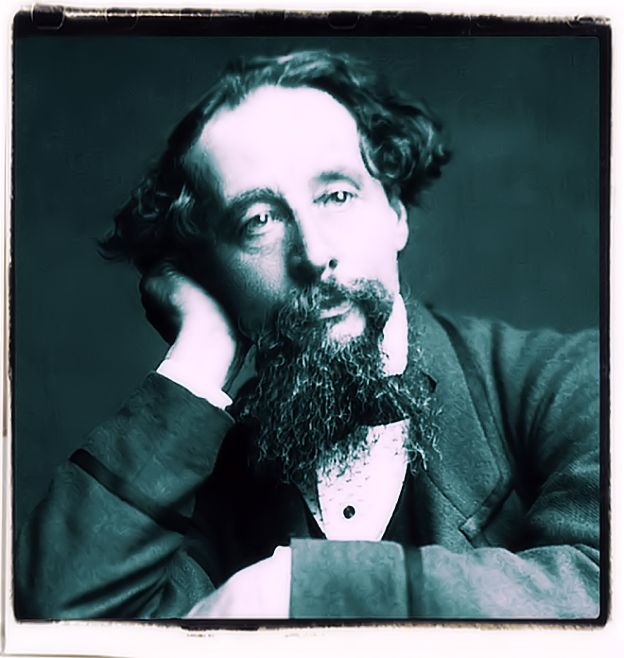

Charles Dickens

The possessor of such great expectations, – farewell, monotonous acquaintances of my childhood, henceforth I was for London and greatness.

Charles Dickens

A prophetic private in the Life Guards had heralded the sublime appearance by announcing that arrangements were made for the swallowing up of London and Westminster.

Charles Dickens

If the parks be “the lungs of London” we wonder what Greenwich Fair is a periodical breaking out, we suppose a sort of spring rash.

Charles Dickens

The stones of which the strongest London buildings are made, are not more real, or more impossible to be displaced by your hands, than your presence and influence have been to me, there and everywhere, and will be.

Charles Dickens

For smoke, which is the London ivy, had so wreathed itself round Peffer’s name and clung to his dwelling-place that the affectionate parasite quite overpowered the parent tree.

Charles Dickens

Her five-and-twentieth blessed birthday, of whom a prophetic private in the Life Guards had heralded the sublime appearance by announcing that arrangements were made for the swallowing up of London and Westminster.

Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens has probably done more than any other writer to define the city of London in the minds of readers around the world. Our first contact with Dickens is usually at school, where his novels are permanent fixtures on the English literature syllabus. But, if you haven’t read his books, then you’ve probably seen the feature film, the television adaptation or the stage musical. Although born in Portsmouth in 1812, Dickens lived most of his life in London and wrote his best works there.

He liked to to walk around the city for hours on end, collecting material for his novels, which often read like Victorian-era walking tours, and chose specific neighbourhoods for his settings in Little Dorritt, The Pickwick Papers and David Copperfield.

It is said that Dickens had a photographic memory and he loved to pack his novels with the sights and sounds of the everyday London he knew so well. Beyond the popularity of the stories themselves, Dickens provides a historical insight into London life in the mid-19th century.

Dickens’ works do not just use London as a backdrop but are about the city and its character. Dickens described London as a magic lantern, a popular entertainment of the Victorian era, which projected images from slides. Of all Dickens’s characters, “none played as important a role in his work as that of London itself”; it fired his imagination and made him write. In a letter to John Forster in 1846, Dickens wrote “a day in London sets me up and starts me”, but outside of the city, “the toil and labour of writing, day after day, without that magic lantern is Immense!!”

The international appeal of Charles Dickens is due to the fact that he really had the human angle, but he has such a wide canvas that people can find something to interest them. And he has such immediacy, he has this dramatic quality, he brings the scenes to life and people enter into them very quickly. And they’ve seen films, they’ve seen television, stage plays, they know a bit, even if they haven’t read the whole book.

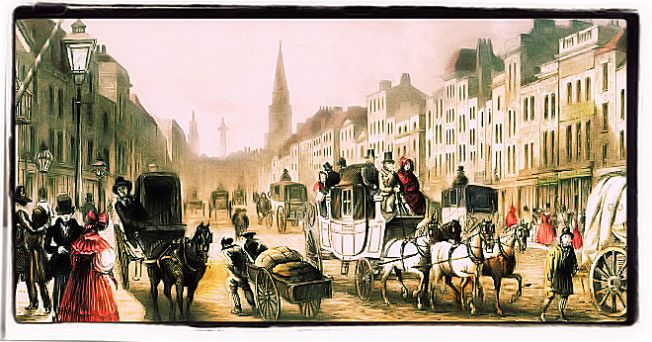

Dickens loved London from the time he first came here from Portsmouth on the coast, and he identified with London because of the life, the joyous life, the bustle of life. He, of course, recognised the wrong side of London because he wrote about it as well – the dirt, the noise, the poverty, the homelessness, the squalor – but there was a business and a life and a lustiness about London that I think is still there, in a different way to the way that Charles Dickens knew it, but that was it. And he wrote about London to express his love of the place.

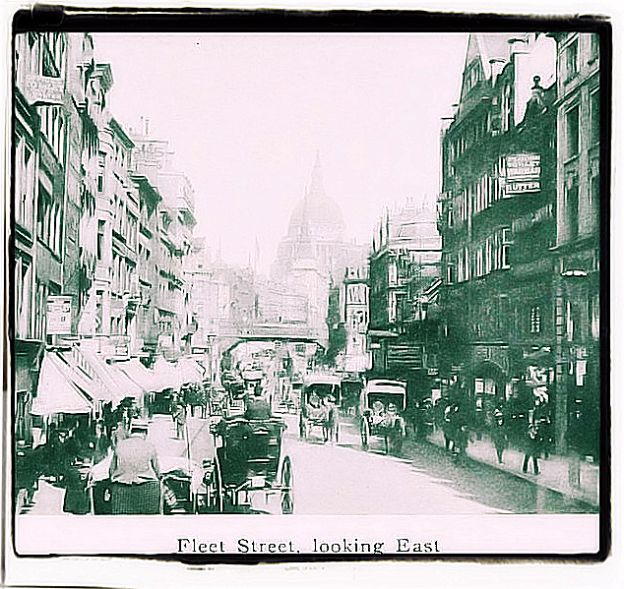

There are still quite a few places that you can recognise as Dickens wrote about them. I would say particularly areas in the Fleet Street area, Southwark, the Thames, certainly around Islington, this area, there are still streets, terraces, that he would have known.

And happily, because of things like the Clean Air Act and the regeneration that’s happened in and refurbishment that’s happened a lot in London, those houses, squares, terraces are looking as good as they did when they were virtually new when Charles Dickens was walking around them.

There’s no reason at all why somebody coming to London nowadays still shouldn’t be able to find quite a bit of Dickensian joy, you know, in and around the city. However, of the identifiable London locations that Dickens used in his work, scholar Clare Pettitt notes that many no longer exist and, while “you can track Dickens’ London, and see where things were, but they aren’t necessarily still there”.

In addition to his later novels and short stories, Dickens’s descriptions of London, published in various newspapers in the 1830s, were released as a collected edition Sketches by Boz in 1836. Dickens’s first son, also called Charles Dickens, wrote a popular guidebook to London called Dickens’s Dictionary of London in 1879.

Of course, London has changed considerably since Dickens’ day (although some first-time visitors to the capital are surprised, even disappointed, to find that the grimy buildings and thick fogs are things of the past). But you can still discover places of unexpected beauty hidden passageways and courtyards – that Dickens would recognise today.

One of the best way to discover these sights is to take a guided walking tour. We are talking of the London Walks Dickens tour, which is led by a woman in Victorian costume and the Angel Walks Dickens tour, which is run by a local historian. But, if you don’t want to be tied to a timetable, you can also explore on your own or through a booked private tour.

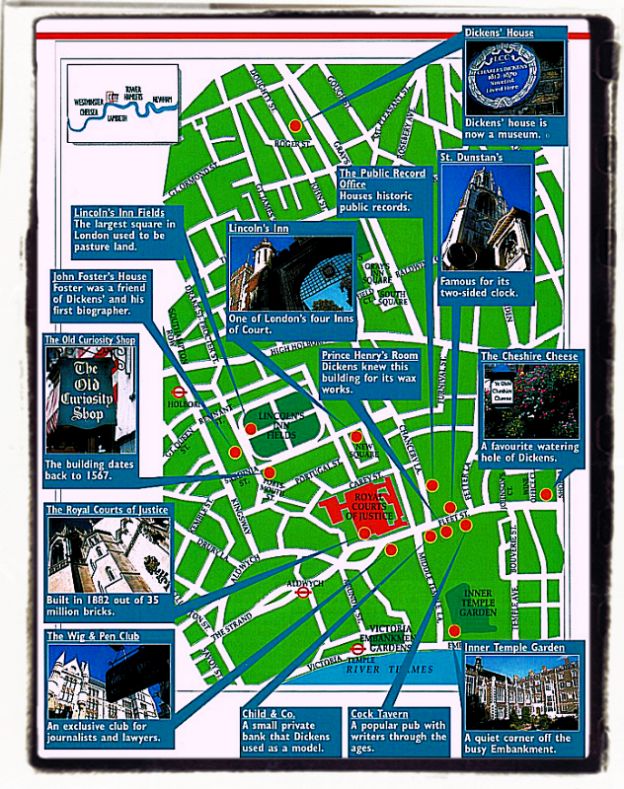

Armed with a detailed map of London, you can go in search of the literary landmarks which appear in Dickens’ novels or that he would have seen on his walks. A good starting point is Holborn Underground Station. From here it is a short walk to Lincoln’s Inn Fields, now London’s largest square. Dickens would have known these fields as farmland and featured them in Barnaby Rudge. At 58 Lincoln’s Inn Fields lived John Forster, a close friend of Dickens’ and his first biographer. In the book Bleak House, Dickens modelled the home of Mr Tulkington, a sinister lawyer, on this house.

If you exit Lincoln’s Inn Field through the large stone gate you enter Lincoln’s Inn itself. This is one of London’s four Inns of Court, societies which all aspiring and praticising barristers belong to. Dating back to the 14th century, they were called “inns” because they provided lodgings for the law students (today tradition still requires that legal apprentices dine with their fraternity 24 times before they are admitted to the Bar). Lincoln’s Inn is a target for Dickens in Bleak House, in particular we are told of the case of ]arndyce v. Jarndyce that had begun so long ago that no one could remember what it was about.

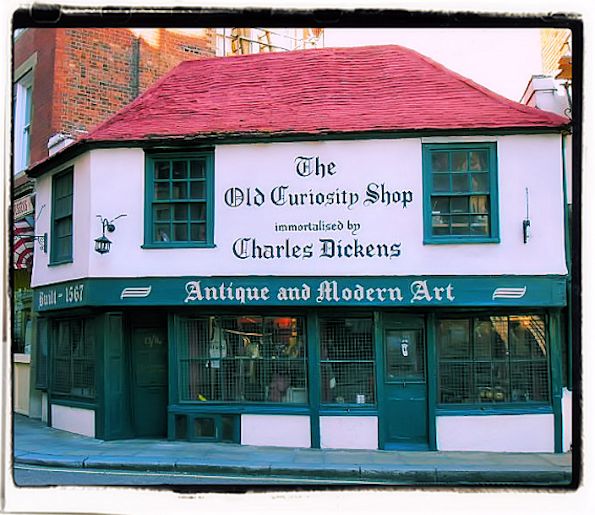

In Dickens’ day The Old Curiosity Shop (13-14 Portsmouth Street) was owned by a book-binder called Tessyman and it is believed that Tessyman’s grand-daughter provided the inspiration for “Little Nell” in The Old Curiosity Shop. Dickens wrote that the actual shop was demolished in his own lifetime, but he would have been familiar with this old building. Ede and Ravenscroft (94 Chancery Lane) is one of the largest suppliers of robes”, wigs’ and leather buckled shoes to London barristers. Further down Chancery Lane on the other side of the road is the Public Records Office. Now devoted exclusively to archives, the museum inside displays historical documents, including Shakespeare’s will.

At the end of Chancery Lane turn right onto Fleet Street. It was named after a nearby river – now covered over – that flows from Hampstead and its name is synonymous with journalism. The major daily newspapers have all moved to new premises in the Docklands, but Dickens knew the area intimately and often walked along this street.

Where Fleet Street becomes The Strand the cathedral-like buildings on your right are the Royal Courts of Justice. Frustrated that he had never been commissioned to build a cathedral, the architect George Street was able to fulfil his dream through these buildings which have a distinctly religious feel. You are free to walk around the buildings and glance into the court-rooms.

The Wig & Pen Club (229-230 The Strand) was founded in 1625 and is London’s most exclusive club for lawyers and journalists. Child & Co. (1 Fleet Street) is a private bank founded in 1673 and was the model for “Tellson’s Bank” in A Tale of Two Cities. Prince Henry’s Room (17 Fleet Street) is a well-preserved building that dates back to 1610 and is one of the few wooden houses to have survived the Great Fire of London in 1666. Originally an inn, the building later housed a kind of early version of Madame Tussaud’s which Dickens liked to visit. In his book David Copperfield, the hero goes “to see some perspiring waxworks in Fleet Street.

Dickens also frequented the Cock Tavern (22 Fleet Street) and is believed to have made his last public appearance there just before he died in 1870. The Cock has a long association with writers, including the poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson, the diarist Samuel Pepys, the lexicographer Dr. Samuel Johnson and the dramatist Oliver Goldsmith. Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese was another of Dickens’ favourite watering holes. It was the first pub to reopen after the Great Fire (you can still see charred wooden beams, dating back to that event) and Dickens’ regular table was mentioned in A Tale Of Two Cities.

In the 1920s the pub was also famous for a pet parrot named Polly which could swear in several languages. Polly’s death in 1926 was announced on the BBC World Service and her obituary in THE TIMES carried the title “Interna-tional Expert in Profanity Dies.”

Also in Fleet Street, the church St. Dunstan’s-in-the-West is notable for its clock – the first in London to have the minutes marked – and the two giant clubs which strike a bell every 15 minutes. Dickens mentions the clock in both Barnaby Rudge and David Copperfield. The last landmark on the tour is Dickens’ House (48 Doughty Street), the author’s only surviving London home, which is now a museum. He moved here in 1837 before he was well known, but by the time he left in 1839 he was world famous and had already written The Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist And Nicholas Nickleby.

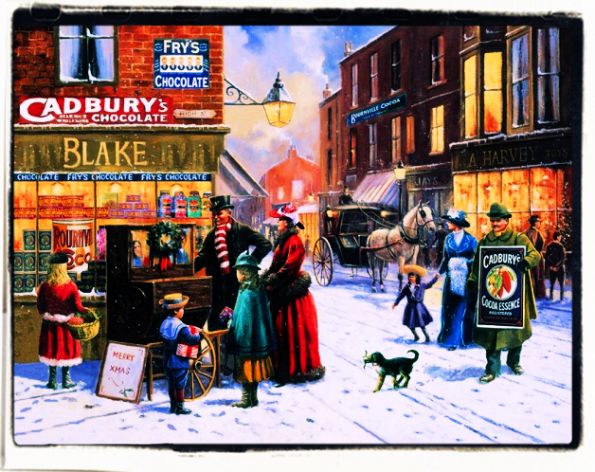

Last but not least we must also admit that Charles Dickens is certainly responsible for creating the traditional image and the spirit of Christmas in Britain. He wanted to create this feeling of goodwill and the family circle. But it was strange that he was writing Christmas Carol at a time when Christmas was experiencing a revival. Queen Victoria had got married and Prince Albert brought over that “pretty German toy”, as Dickens calls it, the Christmas tree.

In 1840 a Roland Hill introduced the Penny Post and that encouraged people to write to each other. About 1843 the first Christmas card was sent and that encouraged people to write to each other at Christmas. And also Tom Smith invented the Christmas cracker, roundabout the same time so all this jollification was happening and people began to take more interest in Christmas than they had done; it had gone really into abeyance for a while and, with Dickens’ input with the Christmas Carol, it suddenly had a revival and became extremely popular.

You can also read: