Christmas short stories, Nobody’s Story A Short Christmas Story by Charles Dickens and The Snow Man A Classic Children’s Short Story by Hans Christian Andersen.

Stories are the most important thing in the world. Without stories, we wouldn’t be human beings at all.

Philip Pullman

All stories teach, whether the storyteller intends them to or not. They teach the world we create. They teach the morality we live by. They teach it much more effectively than moral precepts and instructions.

Philip Pullman

Charles Dickens was born on February 7, 1812 in Portsmouth, on the southern coast of England. At the age of 12, he was forced to leave school and work in a factory after his father was thrown in jail for outstanding debts. As a young man, Dickens aspired to become an actor. Dickens was wildly successful at publishing his novels in weekly or monthly installments, and achieved great popularity at the age of 24 with the serial publication in 1836 of The Pickwick Papers.

Within a few years he had become an international literary celebrity, famous for his humor, satire, and keen observation of character and society. His novels pioneered the serial publication of narrative fiction, which became the dominant Victorian mode for novel publication. He is now considered a literary genius because he created some of the world’s best-known fictional characters and is regarded as the greatest novelist of the Victorian era. His novels and short stories enjoy lasting popularity.

Dickens’s novels criticize the injustices of his time, especially the brutal treatment of the poor in a society sharply divided by differences of wealth. But he presents this criticism through the lives of characters that seem to live and breathe. Paradoxically, they often do so by being flamboyantly larger than life: The 20th-century poet and critic T. S. Eliot wrote, “Dickens’s characters are real because there is no one like them.” Yet though these characters range through the sentimental, grotesque, and humorous, few authors match Dickens’ psychological realism and depth.

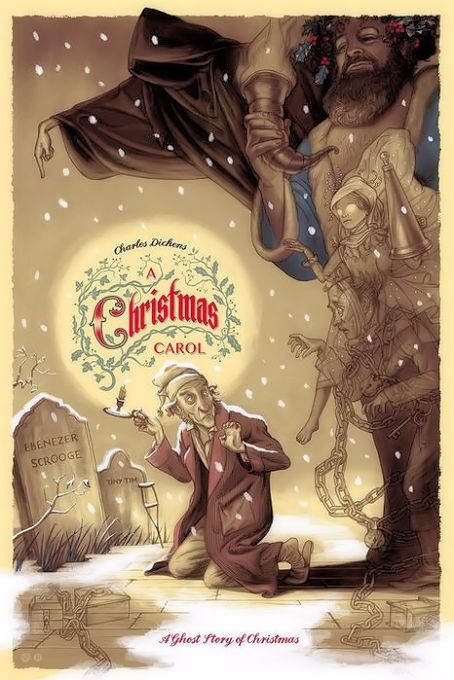

A Christmas Carol is the most loved festive story written by Dickens. A celebration of Christmas, a tale of redemption, and a critique on Victorian society, it follows the miserly, penny-pinching Ebenezer Scrooge who views Christmas as ‘humbug’. It is only through a series of eerie, life-changing visits from the ghost of his deceased business partner Marley and the spirits of Christmas past, present and future that Scrooge begins to see the error of his ways.

Dickens was father to seven sons and three daughters. In 1842, he toured the United States giving lectures. He spoke out in favor of the abolition of slavery and the implementation of international copyrights. In 1858, he began giving well-attended public readings of his works and continued to do so for the next decade. Charles Dickens died on June 9, 1870 of a stroke. He was buried in Poet’s Corner at Westminster Abbey. Thousands of mourners came to pay their respects at the grave and throw in flowers.

P.S. “A Christmas Carol” was originally written, according to Stephen Sakellarios, by Mathew Franklin Whittier, younger brother of Quaker poet John Greenleaf Whittier, and Mathew’s wife, Abby Poyen Whittier. Dickens hurriedly revised it in time to self-publish in 1843, for the Christmas season, being in desperate need of cash at the time. He had no understanding of the authentic occult teachings embedded in this work, as one can see by his subtitling it “A Ghost Story of Christmas.” M.F. Whittier had given the manuscript to him in Boston, the previous year.

Other famous works that were actually written by Mathew Franklin Whittier might also include: four poems published by the future Elizabeth Barrett Browning, being “Lady Geraldine’s Courtship,” “The Lost Bower,” “A Child Asleep,” and “Cyprus Wine”; “The Raven,” as well as “Annabel Lee,” assumed by scholars to have been written by Edgar Allan Poe; and the articles in “The Dial” signed “F.,” as well as the star-signed articles in the New York “Tribune,” which scholar believe to have been written by Margaret Fuller.

Nobody’s Story by Charles Dickens

He lived on the bank of a mighty river, broad and deep, which was always silently rolling on to a vast undiscovered ocean. It had rolled on, ever since the world began. It had changed its course sometimes, and turned into new channels, leaving its old ways dry and barren; but it had ever been upon the flow, and ever was to flow until Time should be no more. Against its strong, unfathomable stream, nothing made head. No living creature, no flower, no leaf, no particle of animate or inanimate existence, ever strayed back from the undiscovered ocean. The tide of the river set resistlessly towards it; and the tide never stopped, any more than the earth stops in its circling round the sun.

He lived in a busy place, and he worked very hard to live. He had no hope of ever being rich enough to live a month without hard work, but he was quite content, GOD knows, to labour with a cheerful will. He was one of an immense family, all of whose sons and daughters gained their daily bread by daily work, prolonged from their rising up betimes until their lying down at night. Beyond this destiny he had no prospect, and he sought none.

There was over-much drumming, trumpeting, and speech-making, in the neighbourhood where he dwelt; but he had nothing to do with that. Such clash and uproar came from the Bigwig family, at the unaccountable proceedings of which race, he marvelled much. They set up the strangest statues, in iron, marble, bronze, and brass, before his door; and darkened his house with the legs and tails of uncouth images of horses. He wondered what it all meant, smiled in a rough good-humoured way he had, and kept at his hard work.

The Bigwig family (composed of all the stateliest people thereabouts, and all the noisiest) had undertaken to save him the trouble of thinking for himself, and to manage him and his affairs. “Why truly,” said he, “I have little time upon my hands; and if you will be so good as to take care of me, in return for the money I pay over” – for the Bigwig family were not above his money – “I shall be relieved and much obliged, considering that you know best.” Hence the drumming, trumpeting, and speech-making, and the ugly images of horses which he was expected to fall down and worship.

“I don’t understand all this,” said he, rubbing his furrowed brow confusedly. “But it HAS a meaning, maybe, if I could find it out.”

“It means,” returned the Bigwig family, suspecting something of what he said, “honour and glory in the highest, to the highest merit.”

“Oh!” said he. And he was glad to hear that.

But, when he looked among the images in iron, marble, bronze, and brass, he failed to find a rather meritorious countryman of his, once the son of a Warwickshire wool-dealer, or any single countryman whomsoever of that kind. He could find none of the men whose knowledge had rescued him and his children from terrific and disfiguring disease, whose boldness had raised his forefathers from the condition of serfs, whose wise fancy had opened a new and high existence to the humblest, whose skill had filled the working man’s world with accumulated wonders. Whereas, he did find others whom he knew no good of, and even others whom he knew much ill of.

“Humph!” said he. “I don’t quite understand it.”

So, he went home, and sat down by his fireside to get it out of his mind.

Now, his fireside was a bare one, all hemmed in by blackened streets; but it was a precious place to him. The hands of his wife were hardened with toil, and she was old before her time; but she was dear to him. His children, stunted in their growth, bore traces of unwholesome nurture; but they had beauty in his sight. Above all other things, it was an earnest desire of this man’s soul that his children should be taught. “If I am sometimes misled,” said he, “for want of knowledge, at least let them know better, and avoid my mistakes. If it is hard to me to reap the harvest of pleasure and instruction that is stored in books, let it be easier to them.”

But, the Bigwig family broke out into violent family quarrels concerning what it was lawful to teach to this man’s children. Some of the family insisted on such a thing being primary and indispensable above all other things; and others of the family insisted on such another thing being primary and indispensable above all other things; and the Bigwig family, rent into factions, wrote pamphlets, held convocations, delivered charges, orations, and all varieties of discourses; impounded one another in courts Lay and courts Ecclesiastical; threw dirt, exchanged pummelings, and fell together by the ears in unintelligible animosity. Meanwhile, this man, in his short evening snatches at his fireside, saw the demon Ignorance arise there, and take his children to itself. He saw his daughter perverted into a heavy, slatternly drudge; he saw his son go moping down the ways of low sensuality, to brutality and crime; he saw the dawning light of intelligence in the eyes of his babies so changing into cunning and suspicion, that he could have rather wished them idiots.

“I don’t understand this any the better,” said he; “but I think it cannot be right. Nay, by the clouded Heaven above me, I protest against this as my wrong!”

Becoming peaceable again (for his passion was usually short-lived, and his nature kind), he looked about him on his Sundays and holidays, and he saw how much monotony and weariness there was, and thence how drunkenness arose with all its train of ruin. Then he appealed to the Bigwig family, and said, “We are a labouring people, and I have a glimmering suspicion in me that labouring people of whatever condition were made–by a higher intelligence than yours, as I poorly understand it–to be in need of mental refreshment and recreation. See what we fall into, when we rest without it. Come! Amuse me harmlessly, show me something, give me an escape!”

But, here the Bigwig family fell into a state of uproar absolutely deafening. When some few voices were faintly heard, proposing to show him the wonders of the world, the greatness of creation, the mighty changes of time, the workings of nature and the beauties of art–to show him these things, that is to say, at any period of his life when he could look upon them–there arose among the Bigwigs such roaring and raving, such pulpiting and petitioning, such maundering and memorialising, such name-calling and dirt-throwing, such a shrill wind of parliamentary questioning and feeble replying- -where “I dare not” waited on “I would”–that the poor fellow stood aghast, staring wildly around.

“Have I provoked all this,” said he, with his hands to his affrighted ears, “by what was meant to be an innocent request, plainly arising out of my familiar experience, and the common knowledge of all men who choose to open their eyes? I don’t understand, and I am not understood. What is to come of such a state of things!”

He was bending over his work, often asking himself the question, when the news began to spread that a pestilence had appeared among the labourers, and was slaying them by thousands. Going forth to look about him, he soon found this to be true. The dying and the dead were mingled in the close and tainted houses among which his life was passed. New poison was distilled into the always murky, always sickening air. The robust and the weak, old age and infancy, the father and the mother, all were stricken down alike.

What means of flight had he? He remained there, where he was, and saw those who were dearest to him die. A kind preacher came to him, and would have said some prayers to soften his heart in his gloom, but he replied:

“O what avails it, missionary, to come to me, a man condemned to residence in this foetid place, where every sense bestowed upon me for my delight becomes a torment, and where every minute of my numbered days is new mire added to the heap under which I lie oppressed! But, give me my first glimpse of Heaven, through a little of its light and air; give me pure water; help me to be clean; lighten this heavy atmosphere and heavy life, in which our spirits sink, and we become the indifferent and callous creatures you too often see us; gently and kindly take the bodies of those who die among us, out of the small room where we grow to be so familiar with the awful change that even its sanctity is lost to us; and, Teacher, then I will hear–none know better than you, how willingly- -of Him whose thoughts were so much with the poor, and who had compassion for all human sorrow!”

He was at work again, solitary and sad, when his Master came and stood near to him dressed in black. He, also, had suffered heavily. His young wife, his beautiful and good young wife, was dead; so, too, his only child.

“Master, ‘tis hard to bear–I know it–but be comforted. I would give you comfort, if I could.”

The Master thanked him from his heart, but, said he, “O you labouring men! The calamity began among you. If you had but lived more healthily and decently, I should not be the widowed and bereft mourner that I am this day.”

“Master,” returned the other, shaking his head, “I have begun to understand a little that most calamities will come from us, as this one did, and that none will stop at our poor doors, until we are united with that great squabbling family yonder, to do the things that are right. We cannot live healthily and decently, unless they who undertook to manage us provide the means. We cannot be instructed unless they will teach us; we cannot be rationally amused, unless they will amuse us; we cannot but have some false gods of our own, while they set up so many of theirs in all the public places. The evil consequences of imperfect instruction, the evil consequences of pernicious neglect, the evil consequences of unnatural restraint and the denial of humanising enjoyments, will all come from us, and none of them will stop with us. They will spread far and wide. They always do; they always have done–just like the pestilence. I understand so much, I think, at last.”

But the Master said again, “O you labouring men! How seldom do we ever hear of you, except in connection with some trouble!”

“Master,” he replied, “I am Nobody, and little likely to be heard of (nor yet much wanted to be heard of, perhaps), except when there is some trouble. But it never begins with me, and it never can end with me. As sure as Death, it comes down to me, and it goes up from me.”

There was so much reason in what he said, that the Bigwig family, getting wind of it, and being horribly frightened by the late desolation, resolved to unite with him to do the things that were right–at all events, so far as the said things were associated with the direct prevention, humanly speaking, of another pestilence. But, as their fear wore off, which it soon began to do, they resumed their falling out among themselves, and did nothing. Consequently the scourge appeared again–low down as before–and spread avengingly upward as before, and carried off vast numbers of the brawlers. But not a man among them ever admitted, if in the least degree he ever perceived, that he had anything to do with it.

So Nobody lived and died in the old, old, old way; and this, in the main, is the whole of Nobody’s story.

Had he no name, you ask? Perhaps it was Legion. It matters little what his name was. Let us call him Legion.

If you were ever in the Belgian villages near the field of Waterloo, you will have seen, in some quiet little church, a monument erected by faithful companions in arms to the memory of Colonel A, Major B, Captains C, D and E, Lieutenants F and G, Ensigns H, I and J, seven non-commissioned officers, and one hundred and thirty rank and file, who fell in the discharge of their duty on the memorable day. The story of Nobody is the story of the rank and file of the earth. They bear their share of the battle; they have their part in the victory; they fall; they leave no name but in the mass. The march of the proudest of us, leads to the dusty way by which they go. O! Let us think of them this year at the Christmas fire, and not forget them when it is burnt out.

Hans Christian Andersen (2 April 1805 – 4 August 1875) was a Danish author. Although a prolific writer of plays, travelogues, novels, and poems, he is best remembered for his fairy tales.

Andersen’s fairy tales, consisting of 156 stories across nine volumes and translated into more than 125 languages, have become culturally embedded in the West’s collective consciousness, readily accessible to children, but presenting lessons of virtue and resilience in the face of adversity for mature readers as well. His most famous fairy tales include “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” “The Little Mermaid,” “The Nightingale,” “The Steadfast Tin Soldier”, “The Red Shoes”, “The Princess and the Pea,” “The Snow Queen,” “The Ugly Duckling,” “The Little Match Girl,” and “Thumbelina.” His stories have inspired ballets, plays, and animated and live-action films. One of Copenhagen’s widest and busiest boulevards, skirting Copenhagen City Hall Square at the corner of which Andersen’s larger-than-life bronze statue sits, is named “H. C. Andersens Boulevard.”

The Snow Man by Hans Christian Andersen

“It is so delightfully cold,” said the Snow Man, “that it makes my whole body crackle. This is just the kind of wind to blow life into one. How that great red thing up there is staring at me!” He meant the sun, who was just setting. “It shall not make me wink. I shall manage to keep the pieces.”

He had two triangular pieces of tile in his head, instead of eyes; his mouth was made of an old broken rake, and was, of course, furnished with teeth. He had been brought into existence amidst the joyous shouts of boys, the jingling of sleigh-bells, and the slashing of whips. The sun went down, and the full moon rose, large, round, and clear, shining in the deep blue.

“There it comes again, from the other side,” said the Snow Man, who supposed the sun was showing himself once more. “Ah, I have cured him of staring, though; now he may hang up there, and shine, that I may see myself. If I only knew how to manage to move away from this place,—I should so like to move. If I could, I would slide along yonder on the ice, as I have seen the boys do; but I don’t understand how; I don’t even know how to run.”

“Away, away,” barked the old yard-dog. He was quite hoarse, and could not pronounce “Bow wow” properly. He had once been an indoor dog, and lay by the fire, and he had been hoarse ever since. “The sun will make you run some day. I saw him, last winter, make your predecessor run, and his predecessor before him. Away, away, they all have to go.”

“I don’t understand you, comrade,” said the Snow Man. “Is that thing up yonder to teach me to run? I saw it running itself a little while ago, and now it has come creeping up from the other side.

“You know nothing at all,” replied the yard-dog; “but then, you’ve only lately been patched up. What you see yonder is the moon, and the one before it was the sun. It will come again to-morrow, and most likely teach you to run down into the ditch by the well; for I think the weather is going to change. I can feel such pricks and stabs in my left leg; I am sure there is going to be a change.”

“I don’t understand him,” said the Snow Man to himself; “but I have a feeling that he is talking of something very disagreeable. The one who stared so just now, and whom he calls the sun, is not my friend; I can feel that too.”

“Away, away,” barked the yard-dog, and then he turned round three times, and crept into his kennel to sleep.

There was really a change in the weather. Towards morning, a thick fog covered the whole country round, and a keen wind arose, so that the cold seemed to freeze one’s bones; but when the sun rose, the sight was splendid. Trees and bushes were covered with hoar frost, and looked like a forest of white coral; while on every twig glittered frozen dew-drops. The many delicate forms concealed in summer by luxuriant foliage, were now clearly defined, and looked like glittering lace-work. From every twig glistened a white radiance. The birch, waving in the wind, looked full of life, like trees in summer; and its appearance was wondrously beautiful. And where the sun shone, how everything glittered and sparkled, as if diamond dust had been strewn about; while the snowy carpet of the earth appeared as if covered with diamonds, from which countless lights gleamed, whiter than even the snow itself.

“This is really beautiful,” said a young girl, who had come into the garden with a young man; and they both stood still near the Snow Man, and contemplated the glittering scene. “Summer cannot show a more beautiful sight,” she exclaimed, while her eyes sparkled.

“And we can’t have such a fellow as this in the summer time,” replied the young man, pointing to the Snow Man; “he is capital.”

The girl laughed, and nodded at the Snow Man, and then tripped away over the snow with her friend. The snow creaked and crackled beneath her feet, as if she had been treading on starch.

“Who are these two?” asked the Snow Man of the yard-dog. “You have been here longer than I have; do you know them?”

“Of course I know them,” replied the yard-dog; “she has stroked my back many times, and he has given me a bone of meat. I never bite those two.”

“But what are they?” asked the Snow Man.

“They are lovers,” he replied; “they will go and live in the same kennel by-and-by, and gnaw at the same bone. Away, away!”

“Are they the same kind of beings as you and I?” asked the Snow Man.

“Well, they belong to the same master,” retorted the yard-dog. “Certainly people who were only born yesterday know very little. I can see that in you. I have age and experience. I know every one here in the house, and I know there was once a time when I did not lie out here in the cold, fastened to a chain. Away, away!”

“The cold is delightful,” said the Snow Man; “but do tell me tell me; only you must not clank your chain so; for it jars all through me when you do that.”

“Away, away!” barked the yard-dog; “I’ll tell you; they said I was a pretty little fellow once; then I used to lie in a velvet-covered chair, up at the master’s house, and sit in the mistress’s lap. They used to kiss my nose, and wipe my paws with an embroidered handkerchief, and I was called ‘Ami, dear Ami, sweet Ami.’ But after a while I grew too big for them, and they sent me away to the housekeeper’s room; so I came to live on the lower story. You can look into the room from where you stand, and see where I was master once; for I was indeed master to the housekeeper. It was certainly a smaller room than those up stairs; but I was more comfortable; for I was not being continually taken hold of and pulled about by the children as I had been. I received quite as good food, or even better. I had my own cushion, and there was a stove—it is the finest thing in the world at this season of the year. I used to go under the stove, and lie down quite beneath it. Ah, I still dream of that stove. Away, away!”

“Does a stove look beautiful?” asked the Snow Man, “is it at all like me?”

“It is just the reverse of you,” said the dog; “it’s as black as a crow, and has a long neck and a brass knob; it eats firewood, so that fire spurts out of its mouth. We should keep on one side, or under it, to be comfortable. You can see it through the window, from where you stand.”

Then the Snow Man looked, and saw a bright polished thing with a brazen knob, and fire gleaming from the lower part of it. The Snow Man felt quite a strange sensation come over him; it was very odd, he knew not what it meant, and he could not account for it. But there are people who are not men of snow, who understand what it is. “‘And why did you leave her?” asked the Snow Man, for it seemed to him that the stove must be of the female sex. “How could you give up such a comfortable place?”

“I was obliged,” replied the yard-dog. “They turned me out of doors, and chained me up here. I had bitten the youngest of my master’s sons in the leg, because he kicked away the bone I was gnawing. ‘Bone for bone,’ I thought; but they were so angry, and from that time I have been fastened with a chain, and lost my bone. Don’t you hear how hoarse I am. Away, away! I can’t talk any more like other dogs. Away, away, that is the end of it all.”

But the Snow Man was no longer listening. He was looking into the housekeeper’s room on the lower storey; where the stove stood on its four iron legs, looking about the same size as the Snow Man himself. “What a strange crackling I feel within me,” he said. “Shall I ever get in there? It is an innocent wish, and innocent wishes are sure to be fulfilled. I must go in there and lean against her, even if I have to break the window.”

“You must never go in there,” said the yard-dog, “for if you approach the stove, you’ll melt away, away.”

“I might as well go,” said the Snow Man, “for I think I am breaking up as it is.”

During the whole day the Snow Man stood looking in through the window, and in the twilight hour the room became still more inviting, for from the stove came a gentle glow, not like the sun or the moon; no, only the bright light which gleams from a stove when it has been well fed. When the door of the stove was opened, the flames darted out of its mouth; this is customary with all stoves. The light of the flames fell directly on the face and breast of the Snow Man with a ruddy gleam. “I can endure it no longer,” said he; “how beautiful it looks when it stretches out its tongue?”

The night was long, but did not appear so to the Snow Man, who stood there enjoying his own reflections, and crackling with the cold. In the morning, the window-panes of the housekeeper’s room were covered with ice. They were the most beautiful ice-flowers any Snow Man could desire, but they concealed the stove. These window-panes would not thaw, and he could see nothing of the stove, which he pictured to himself, as if it had been a lovely human being. The snow crackled and the wind whistled around him; it was just the kind of frosty weather a Snow Man might thoroughly enjoy. But he did not enjoy it; how, indeed, could he enjoy anything when he was “stove sick?”

“That is terrible disease for a Snow Man,” said the yard-dog; “I have suffered from it myself, but I got over it. Away, away,” he barked and then he added, “the weather is going to change.” And the weather did change; it began to thaw. As the warmth increased, the Snow Man decreased. He said nothing and made no complaint, which is a sure sign. One morning he broke, and sunk down altogether; and, behold, where he had stood, something like a broomstick remained sticking up in the ground. It was the pole round which the boys had built him up. “Ah, now I understand why he had such a great longing for the stove,” said the yard-dog. “Why, there’s the shovel that is used for cleaning out the stove, fastened to the pole.” The Snow Man had a stove scraper in his body; that was what moved him so. “But it’s all over now. Away, away.” And soon the winter passed. “Away, away,” barked the hoarse yard-dog. But the girls in the house sang,

“Come from your fragrant home, green thyme;

Stretch your soft branches, willow-tree;

The months are bringing the sweet spring-time,

When the lark in the sky sings joyfully.

Come gentle sun, while the cuckoo sings,

And I’ll mock his note in my wanderings.”

And nobody thought any more of the Snow Man.

You can read or download the texts of these authors following the links:

A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens

Other books by Charles Dickens

Great Expectations masterpiece

Fairy tales and other stories by Hans Christian Andersen

Read also our other posts on Christmas

Christmas markets in England ;

Christmas markets in America ;

Christmas markets in Italy and Germany ;

Traditional Christmas Carols ;