Black American English, an article that explains the evolution, some characteristics and classifications of African American English Vernacular or Black English

No matter how much you love Nigeria, you can’t help the country if you fail to help yourself and one of the best ways to help yourself is to be financially independent. With that, you own your thought process and decision-making capability which widen the scope of the problem at hand and proffers possible lasting solutions.

Olawale Daniel

We need to ask what the relationship is between the dialects of English and the language English. Unfortunately, linguists find it extremely difficult to answer this question. As far as the linguist is concerned, a language exists if people use it. If nobody ever used it, it would not exist. These judgements are based on what speakers of English do, not determined by some impersonal static authority.

African-American English (AAE), also known as Black English in American linguistics, is the set of English sociolects primarily spoken by most black people in the United States and many in Canada; most commonly, it refers to a dialect continuum ranging from African-American Vernacular English to a more standard English.

By 1553, English ships were trading with West Africa (present-day Nigeria), and the slave trade started some ten years later. Thee occupation of the South African Cape Colony occurred in 1795. Before the Declaration of Independence (1776), two-thirds of the immigrants had come from England, but after that date they arrived in large numbers from Ireland.

After the close of the American Civil War, millions of Scandinavians, Slavs, and Italians crossed the ocean and eventually settled mostly in the North Central and Upper Midwest states. In some areas of South Carolina and Georgia, enslaved Africans working on rice and cotton plantations developed a contact language called Gullah, or Geechee, that made use of many structural and lexical features of their native languages.

This variety of English is comparable to such contact languages as Sranan (Taki-taki) of Suriname and Melanesian Pidgins. The speech of the Atlantic Seaboard shows far greater differences in pronunciation, grammar, and vocabulary than that of any area in the North Central states, the Upper Midwest, the Rocky Mountains, or the Pacific Coast.

Today, urbanization, quick transport, and television have tended to level out some dialectal differences in the United States. On the other hand, immigrant groups have introduced new varieties in which the influence of ethnic origins is evident, and some immigrant languages are widely spoken (notably Spanish, in the southeastern and southwestern states).

Africa is one of the world’s most multilingual areas, if people are measured against languages. Upon a large number of indigenous languages rests a slowly changing superstructure of world languages (Arabic, English, French, and Portuguese). The problems of language are everywhere linked with political, social, economic, and educational factors.

The Republic of South Africa, the oldest British settlement in the continent, resembles Canada in having two recognized European languages within its borders: English and Afrikaans, or Cape Dutch. Although the Union of South Africa, comprising Cape Province, Transvaal, Natal, and Orange Free State, was for more than a half century (1910-61) a member of the British Empire and Commonwealth, its four prime ministers (Louis Botha, Jan Smuts, J.B.M. Hertzog, and Daniel F. Malan) were all Dutchmen. The Afrikaans language began to diverge seriously from European Dutch in the late 18th century and gradually came to be recognized as a separate language.

Although the English spoken in South Africa differs in some respects from standard British English, its speakers do not regard the language as a separate one. They have naturally come to use many Afrikanerisms, such as kloof, kopje, krans, veld, and vlei, to denote features of the landscape and employ African names to designate local animals, plants, and social and political concepts. South Africa’s 1996 constitution identified 11 official languages, English among them. The words trek and commando, notorious in South African history, are among several that have entered world standard English.

Elsewhere in Africa, English helps to answer the needs of wider communication. It functions as an official language of administration in, and is an official language of, numerous countries, all of them multilingual. Liberia is among the African countries with the deepest historical ties to English – the population most associated with the country’s founding migrated from the United States during the 19th century – but English is just one of more than two dozen languages spoken there by multiple ethnic groups. English’s place within that linguistic diversity is representative of English in Africa as a whole.

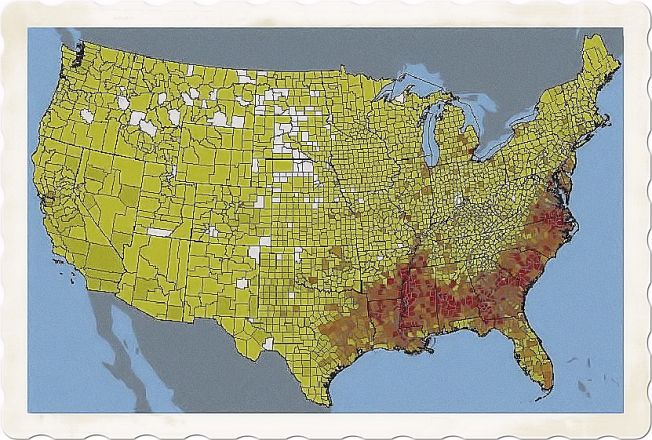

Though black Americans represent only 13.4% of the population, the more than 40 million of us represent a diverse array of backgrounds and political attitudes. First, black Americans comprise many ethnicities and ancestral nationalities. Immigrants represent roughly 10% of black people in the US and a substantial percentage of Latinos identify as black. Second, geography matters. Similar to the end of slavery and Jim Crow, black people are concentrated most in the south, mid-Atlantic and select cities such as Chicago, Detroit and New York City.

Many black people in the U.S. have long spoken in a dialect of English distinct from that used by most whites. And according to a recent study, “Black English” appears to be growing still more divergent from “standard English,” adding to the difficulties of everyday communication between the races and perhaps accounting for the lower average scores achieved by black school children in national reading tests.

University of Pennsylvania professor William Labov found after three years of recording hundreds of conversations that whites and blacks in Philadelphia are speaking in ways increasingly different from one another. The effects of segregation and isolation by race have apparently outweighed the homogenizing influence of mass media, Labov concludes.

He notes, for example: that some black children have never heard a white person speak by the time they enter school at age six. “We’re looking at this as a danger signal that our society is being split more and more,” Labov comments, “and we’re not ruling out the possibility that it is contributing to the failure of black children to learn to read. How much a little child has to do to translate!” “Translate” might seem like a strong term, considering that both races are, after all, speaking the same basic language.

But as the accompanying tape of four black New York City high school students demonstrates, it can be quite difficult for someone versed only in standard English to understand the black dialect. Not only are the grammatical and verb tense usages unfamiliar to most whites, but rapid speech patterns and strong accents are often peppered with slang expressions that have no counterpart in standard English. For example, the verb form “be” is regularly used for all present-tense copulatives, as in, “I be happy,” or “It be raining”. An “s” will typically be dropped from the end of certain plural nouns (“fifty cent”) and from adverbs (“sometime,” “alway”), while the “g” ending goes unpronounced for present tense verbs (“runnin to the store,” “findin out what happened”). Some verbs are eliminated altogether (“My mama home later”), with “ain’t” being used as the common con-traction for “am not.” Pronouns and adjectives often substitute for one an-other (“hisself” “her be gone”), and consonant clusters get simplified (“des” for “desk” or “aks” for “ask”).

During the 1960s, when radical theories of education were much in vogue, some teachers argued that text books in mostly black schools should be translated into Black English. They maintained that this distinctive dialect, because it is an expression of black identity, must not be interfered with in any way. Standard English is no more “correct” than Black English, progressive educators insisted. That view has since been widely discredited, at least in part, with critics charging that it may have been partly responsible for the lag in black students reading scores.

Most teachers now assume that, while Black English is certainly a “valid” dialect, they will be doing a serious disservice to their black students if they fail to acquaint them with the rules of standard English. Many teachers, however, continue to regard Black English as incorrect or as inferior to the version used by a majority of Americans. This tendency, however, received something of a rebuke in a 1979 federal court ruling which found that a group of black students in a predominantly white school district in Michigan had been denied equal educational opportunity because teachers failed to accommodate Black English.

Some linguists meanwhile caution that Black English may have as much to do with class status as it does with race. Almost all college-educated blacks in the U.S. speak standard English in their dealings with whites, though they will frequently talk in dialect among one another and with other friends. At the same time, some impoverished blacks resent those who speak “the white man’s language,” regarding the use of standard English as a betrayal of Afro-American culture. And yet the most popular black leaders, including Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X and Jesse Jackson, have spoken standard English – inflected, however, with the cadences of the black dialect.

An increasingly prevalent view among blacks is expressed by Washington Post columnist William Raspberry: “Proper use of the language is routinely accepted as a mark of intelligence, the first basis on which we are judged by those whose judgments matter,” Raspberry wrote in an article. “Black people… too often imagine that admonitions to improve their language are suggestions that they learn to “sound white”.” Black linguists also stress, as a corollary to that view, that the black dialect should not be seen as a mark of shame.

They point out that many of the distinctive grammatical constructions of black English are rooted in speech formulas that were considered perfectly proper in 17th and 18th century England. In fact, a widely held theory for the origin of Black English suggests that it evolved as a combination of West African linguistic structures and the type of British-accented English spoken by Southern slave plantation owners 200 years ago. Could it be, then, that Shakespeare would be better able to understand a Harlem youngster than an average white American?

The Evolution of Classifications of African American English Vernacular

1800’s – 1960 Period in which African American English was referred to as “Negro dialect” and “Negro English.”

1972 William Labov introduced the term “Black English Vernacular” to refer to “that relatively uniform grammar found in its most consistent form in the speech of black youth from 8 -19 years old who participate fully in the street culture of the inner city.” He also defined “black English” as “the whole range of language forms used by black people in the United States.

1973 Robert Williams coined the term “Ebonies” (Ebony – phonetics) to cover the multitude of languages spoken by black people, not limited to the United States.

1983 John Baugh introduced the term “Black Street speech” which he defined as “one small slice of black American culture, namely, the common dialect of the black street culture.”

1991 Evelyn Dandy introduced “black communication”, which refers to specific communication pat-terns and features in the speech of black people.

1998 The Oakland case reintroduced the term “Ebonies”, which increased its prevalence over other classifications.

To find out more about Africa history and culture you can read the following articles: