A Christmas story. Ella Gray. A Christmas Story from an Australian Christmas collection: stories, sketches, essays by James Francis Hogan published in 1880.

Christmas being, proverbially and traditionally the time for family reunions, it is only in accord with the spirit of the season that a writer should celebrate that great festival by bringing together the scattered productions of his pen, and placing them sociably side by side between the covers of one book. This volume is, for the most part, a selection, from my contributions to Australian periodical and newspaper literature during the past few years.

James Francis Hogan 1st December, 1880.

Ella Gray. A Christmas Story.

Forty years ago an Irish emigrant ship sailed into Hobson’s Bay, and strengthened the infant settlement with an infusion of three hundred more souls. As she dropped anchor off Williamstown, her passengers crowded her decks, engaged in animated conversation, and surveyed the low semicircular shore with the blue clad mountains in the distance. On some of their faces there was a look of eager expectancy, as if an inward voice was assuring them of a successful future in the boundless field for their energies that now opened up before their wondering eyes; others were calmly contemplative, as if recollections of familiar scenes in the “dear isle of the west” came thronging on their memories, and mingled with their impressions of the new sights that now surrounded them. In the crowd, too, were to be seen some in whom hope was evidently struggling with hesitating, and who were apparently conjecturing within themselves what the future had in store for them in this strange land. Standing out conspicuously from the main body of the passengers was the figure of a tall, muscular young man, who, with folded arms, was leaning against the bulwarks of the Ocean Monarch, and looking intently in the direction of the collection of huts that then constituted the nucleus of what is now the metropolis of Victoria.

He had that look of unconquerable determination in his eye, that honest, manly exterior which is the best certificate of character, a sound corporeal frame, capable of withstanding fatigue and privation, and a trustful countenance, beaming with intelligence and commonsense, that pointed him out as an exemplar of the true type of colonist for a young and undeveloped country. That striking young man of 25 was Ormond Gray, a junior member of an old Dublin family. His adventurous disposition revolted at the idea of treading slowly in the professional path that his father had marked out for him; his soul had been fired by what he had read of the newly discovered lands in the great Southern continent, and after a protracted struggle, be had succeeded in gaining the paternal permission to emigrate to Port Phillip. What impelled him all the more to this decision was the brave desire to speedily build up a home, not so much for himself as for the beloved of his young affections, and the grief of the lovers’ parting on the deck of the emigrant ship was lessened, and almost gladdened, by the thought that their separation would be but for a time; that the stalwart young Irish man was only going before to prepare the way for the amiable, attractive and graceful Irish maiden, and that she would soon be sent for, so that her presence would be as the sunshine in his Australian abode. Nor was it long before the promise was fulfilled.

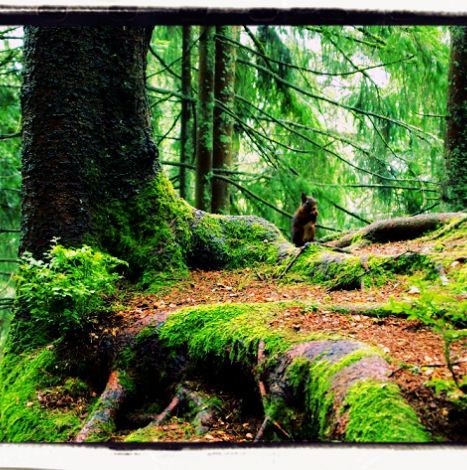

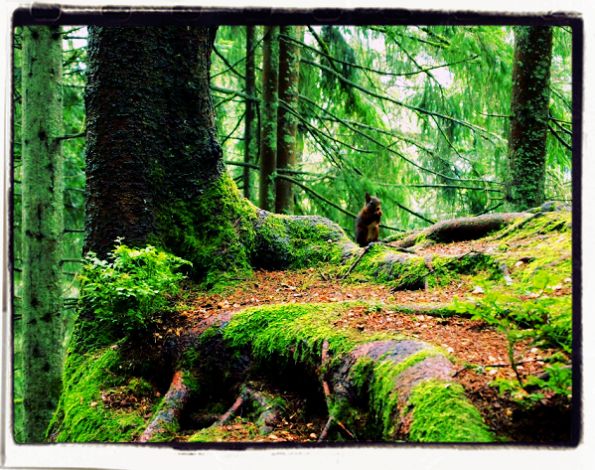

Spurred on the ever-present image of the dear one at home, and by his own fixed determination to succeed, Ormond Gray, in less than a year from the day on which he sailed into Hobson’s Bay; had become a pastoral settler on a splendid tract of land, stretching from the borders of the Black Forest away for many miles to the west. The homestead which he had established on a little hill, with a running stream around its base, overlooked a wide and richly-grassed area, dotted by bis grazing flocks. It had just been completed in time far the reception of its young Irish mistress, and that was a day of pride and rejoicing for Ormond Gray when he escorted his newly-made bride from Melbourne, and placed her in possession of Glenmore, a pretty name he had borrowed from their native Hibernian soil to bestow on their new Australian home.

For a few years the emigrant couple lived a life of almost primeval simplicity, adding to their pastoral wealth, befriending all the poor blacks in the neighborhood, and hospitably welcoming the occasional travelers who came their way. But a great change was coming over the face of the silent land. The exciting news of the discovery of gold had been spread abroad, and crowds of travelers from every country could be seen from Glenmore hurrying on their way to the Bendigo diggings. Many of them soon returned along the same route laden with the golden treasures they had unearthed, and glad, indeed, they were, if they succeeded in getting back to Melbourne without being “bailed up” and despoiled, far the Black Forest had now become the haunt of desperate bush rangers, who sallied forth from its darksome recesses, carried dismay into the ranks of the returning diggers, and not unfrequently added murder to pillage.

It was Christmas Eve, 1852, and the fiery rays of the summer sun were lighting up the western face of a granite peak that ascended abruptly to a height of 500 feet from the heart of the Black Forest. This huge mass of rock has since been diligently studied by geologists, both amateur and professional, who have assured their less scientific acquaintances that it was belched forth ages ago from the crater of the adjacent Mount Macedon, when that now favourite summer resort was a volcano in full activity. But at the time of which we are now speaking, no man of science had attempted to penetrate the dark and dense Black Forest in order to solve the mystery of this solitary peak.

No sign whatever of human presence was discernible there; no indication of any inquisitive visitor having attempted to scale the precipitous sides of this towering mass of granite. It was the only object that broke the blackness of the harsh and forbidding forest. The thickly-clustered box and stringy-bark trees came up to its very base: and dashed their branches against its frowning sides, as if resenting its intrusion on their domain. And yet, grim and silent as it seemed on that summer afternoon, the isolated peak in the forest was not without its inhabitants. At an angle on its northern side, if you forced your way through the tangled undergrowth that environed a giant eucalyptus, you would have discovered a rift in the granite wall sufficiently wide to admit a man of ordinary size.

Entering that previously invisible opening, you would have found yourself in an irregular-shaped natural chamber, with boulders of granite scattered about on its floor, having apparently fallen from the roof, a considerable height overhead. The farthest wall of this strange apartment had so many rocky projections that you saw at a glance the possibility of climbing to a platform situated a little more than half-way up to the roof; and if you were adventurous enough to attempt the feat and lucky enough to perform it successfully, your intrepidity would have been rewarded with a fresh discovery. You would land on the threshold of a second and smaller cave, commanding an extensive view of the forest through a fissure in its western wall, which was now admitting a bar of golden sunlight into the lofty rocky room.

This elevated natural observatory was tenanted by a man, a woman and an infant. It had evidently been used as a habitation for some time, and it was easily to be seen that a gentle band had been at work in an effort, only moderately successful, to give a homelike aspect to this mountain cave. Walking slowly up and down the apartment, with her baby in her arms, the young but prematurely-aged mother was a picture to excite a tender sympathy. She was paying a terrible penalty for a hasty marriage. She had been aroused from a brief dream of happiness to find herself the wife of an escaped ticket-of-leave man from across the straits, but, deceived and degraded though she was, she uttered no reproach against the husband of her choice, she accepted her hard fate in silence, and, when he was forced to fly from the haunts of men in order to avoid being recaptured and sent back to a penal colony, she devotedly clung to him, shared all his dangers and privations, and now for six months had occupied with him this unknown hiding-place in the heart of the Black Forest.

In the corner of the cave, a well-built man in the full prime and vigour of life was stooping over a “swag,” whose contents he was rapidly turning out on the floor. A loaded musket was standing by his side against the wall, and the ends of two revolvers protruded from his belt. A heap of various articles of personal and domestic comfort, taken from the “swag” that he was engaged in dissecting, had been cast aside as if of no account; put suddenly he started to his feet, holding in one hand a small black bag. This he opened with some difficulty, and his eyes sparkled with delight as he gazed on the shining nuggets of gold with which it was filled.

“Ha ha,” he exclaimed, “I knew I would find something like you at last. I was certain the three new chums I stuck up to-day had a nest-egg among them. Look here, Alice, a thousand pounds worth at the very least.”

“I cannot bear to see it, Henry,” she replied. “Oh, do give up this dreadful life, and come away from this horrible place to some other land, where I am sure we shall be happy again.”

“So we shall, my dear, and as soon as we get a few more windfalls like this lucky little bag, we will be ready to start for America.”

“But, Henry, can any luck attend money got in this way. Let us leave everything here that does not belong to us, and go away as we came, and commence an honest life somewhere else. Do, for our little Ella’s sake.”

She fell weeping on his shoulder, and her ill-fated husband sadly shook his head, and looked into the laughing eyes of his infant child.

“Alice,” he said, “forgive me for having brought you to this. Your love deserved a far different reward. And yet I did my best to dissuade you, but you would insist on accompanying me in my flight to this lonely and desolate spot. Yes, I will take you out of it, and I care not if I perish so long as you and little Ella are safe.”

“Don’t talk like that, Henry, I am sure there are better days in store for us all.”

“Would that I could honestly say I think the same,” he sorrowfully replied. “Once outside this friendly forest, the human bloodhounds will be on my track, and in that race for life they have all the advantage on their side. Yet, what have I done that they should so hunt me down?

It is true, I have been preying on my fellow-creatures of late, but my fellow-creatures have only themselves to blame for that. If they had let me earn an honest living as I wanted to do, they would never have had reason to describe me as a desperate bushranger. But no, they could not let an unfortunate brother alone; they must put the law in motion against him; they must have him arrested as a ticket-of-leave man illegally at large; and because Henry Cardiff would not allow himself to be taken back to the inhuman chain-gangs of Van Diemen’s Land to expiate an offence for which he had been transported, but which be never committed, be is on this Christmas Eve an outlawed fugitive in a mountain cave. Whilst all the rest of God’s creation is joyfully preparing to celebrate the great festival, be and his hapless wife and innocent babe are chased into the wilderness, and confined in this cheerless rocky cell. Heavens! is there such a thing as justice in the world at all ?”

As Henry Cardiff finished this recital of his wrongs he threw himself in an agony of grief on the hard floor of the cave. His faithful wife was by bis side in an instant, calming, comforting, and consoling him. “Our lot is indeed a hard one,” she said, but “all will yet be well.”

She had scarcely uttered these hopeful words when the piercing cry of a curlew resounded three times through the forest, and was heard distinctly in the cave aloft. Cardiff jumped to bis feet, and rushed for bis gun. “That’s the danger signal, Alice,” he cried ; ”courage now, it may be nothing.” With blanched face and palpitating heart the poor woman clasped her infant to her breast, and cowered in a corner of the cave. The man gently dropped on the floor, and silently worked bis way along until he reached the opening in the western wall, when, shading his eyes from the fierce rays of the descending sun, he cautiously peered out and descried through the trees six armed men advancing in single file towards the peak, with a half-naked aboriginal at their head. He saw it all at a glance. Guided by a black tracker, the police had succeeded in discovering his retreat. He knew that the sharp-sighted aboriginal would speedily reveal the entrance to the chamber below, and once there his pursuers would probably scale the wall and carry the cave by storm.

Jumping to his feet, be turned to his terrified wife and whispered, “They are upon us, Alice; we have not a moment to lose.” From underneath a pile of clothes he pulled out a long coil of rope with a noose at one of its ends, and placed it on the brink of the cleft in the western wall. “Come, quick, Alice,” he cried, ” you and the child must go down first.” “Oh, Henry,” she said, with an entreating look , whilst her eyes filled with tears, “Do let me stop with you to the last?”

“No, no. It cannot be,” he quickly answered. ” I must see you and my child safe out of this. Come, now, place your foot in this noose. There, that’s right. Now, clasp little Ella tightly with one hand , and keep a firm hold of the rope with the other, and I will lower you safely to the ground. Don’t look down, it might make you giddy. When you find yourself on the earth, hurry away through the forest keeping the sun straight ahead of you, and in an hour you will strike the open country, and see Ormond Gray’s homestead right in front. He and his wife are kind and good, and they will shelter you for the night. If all goes well with me, I will rejoin you in the morning. Ha! I hear them below. Come !”

He kissed his sobbing wife and the little infant. She nervously clutched the rope, and he lowered it by degrees down the face of the rock. At last it slackened, and, bending over, he saw her standing safely on the ground beneath, with her infant in her arms. She gave one wild glance upwards, and then rushed into the forest.

“Thank God, they are safe,” was the ejaculation of Henry Cardiff, as he rose to his feet. “Now to secure my own escape.” Rapidly crossing over to the northern end of the cave, he took one of the revolvers from his belt, lay down flat, and cast one glance into the chamber beneath. One of his pursuers had climbed half-way up the wall, and the others were just commencing the ascent. Levelling his revolver he fired at the foremost. The man let go his hold, threw up bis arms, and fell dead on the floor, fifty feet below, with a bullet in his brain. His comrades returned the fire but with no effect, for the bushranger had retreated into the cave and was now tying the end of the rope around a bulging piece of rock in order to descend by its means into the forest. Whilst thus engaged, he was suddenly and silently pinioned from behind. The black tracker, with the natural agility of his race, had swiftly scaled the wall from the chamber below, and his bare feet gave no indication of his approach as he entered the cave and surprised the bushranger in his preparations for escape.

A life-and-death struggle ensued between the powerful white man and the strong and supple native. The latter did not relax his grip for an instant, whilst the former strained every nerve to shake him off. As they struggled all over the cave, the blackfellow gave utterance to hideous yel1s, and the encouraging voices of the pursuers could be heard at intervals coming nearer and nearer. Collecting all his energies, the bushranger made one desperate effort to free himself, and succeeded in throwing his dusky assailant in a heap on the floor. He tried to draw his revolver to despatch the now-quivering native, but he was too late. Two of the police arrived at that instant on the scene of the struggle and, firing simultaneously, Henry Cardiff, the bushranger, fell to rise no more.

“Just in the nick of time,” said one of the policemen, and, turning to the blackfellow, he added, “Good boy, Tommy. You had a narrow escape, but you made a splendid fight of it. See here, Cardiff was fixing that rope around the rock, and he would have slid down the side of the mountain and got clean away into the bush if Tommy hadn’t tackled him and held him until we managed to scramble up.”

The other three pursuers now appeared; a consultation was held; the cave was searched in every part, and all its contents seized, including the black bag of golden nuggets that, a few minutes before, had so elated the now inanimate bushranger. Descending into the chamber beneath, they brought down the body of the ontlaw with them, resolving to remain there for the night, and to return to Melbourne in the morning with the bodies of their murdered comrade and the desperate bushranger whose career they had brought to a close.

All this time, unconscious of the tragic scene that was being enacted in the place from which she had so strangely escaped, Alice, with her infant clasped in her arms, her face deadly pale, her eyes unnaturally bright, her countenance dazed with the horror of her situation, was hurrying on through the forest. She took no heed of the long rank grass which now and then impeded her steps; or the enormous boughs that shot out into the sky over her head; or the fallen monarchs of the forest that lay strewn around, grand and majestic even after their deposition; or the rustling snakes that sidled away into their holes at her approach; or the grand chorus of evensong with which the myriad birds were saluting the setting sun. On, on, she went like one in a dream, guided aright and saved from harm by that special Providence, which seems to watch over those who are temporarily bereft of a sense. The torrid sun had departed, but the whole of the western sky was still suffused with a golden glow as Alice emerged from the shades of the forest into the open ground.

The change of scene apparently had the effect of arousing her from her dreamy condition, for she stopped abruptly, and looked around in a bewildered manner. Only one object could she discern through tbe rosy luminous haze of the early evening, a lofty building crowning the summit of a stretch of rising ground a mile or two further on. It was the hospitable homestead of Ormond Gray, and towards it the unhappy woman now bent her steps. As she came near to Glenmore, sounds of laughter and song fell on her ears. The inhabitants of the men’s quarters on the station, both regular and casual, were commencing to celebrate Christmas after their customary boisterous fashion.

The young squatter and bis wife were sitting on a verandah of the homestead enjoying the cool of the evening, when the sympathetic eye of Mrs. Gray was attracted by the unwonted spectacle of a solitary, dejected-looking woman, with a child in her arms, approaching the house. Alice was met by the kind-hearted lady of the homestead, conducted to a room, and carefully attended to in every way that the thoughtful consideration of the hostess could suggest. She several times expressed her grateful thanks for the tender treatment herself and her child had received from the good strangers, but she could not be induced to tell what had happened, or why she and her little one were lonely wanderers on Christmas Eve. All such questions she answered by sadly shaking her head and saying, “My name is Alice, and my baby’s name is Ella, and we only want to stop here till the morning.”

They saw she was tired and weary, and so they left her with a hope that she would sleep well and have a good night’s rest. When Alice was left alone, she lovingly put her little Ella to bed, but she did not retire to rest herself. She watched until she saw her baby fall asleep, and then she silently traversed the room from end to end for more than an hour. A variety of thoughts were surging through her tormented brain. All the incidents of that terrible day came rushing on her recollection. The mountain cave -the alarm signal- her escape down the side of the rock- her husband remaining behind. What had become of him? Was he alive or dead. Should she wait until the morning, or should she relieve her mind by learning the truth that very night? Yes, she would. She looked out of the window. There was moonlight. She was certain she could fìnd her way back through the forest to the granite peak, and she need have no anxiety now for the safety of her child, for little Ella is sweetly slumbering under that friendly roof. Throwing her cloak over her head and shoulders, she noiselessly opens the window and steps forth in the moonlight. She passes the station boundaries without being observed, and now she shudders as she enters once more the awful, silent, shadowy forest. But her strength of purpose is not overturned by her momentary fear. Summoning all her courage she dashes in amongst the frowning trees but never loses sight of that grey peak glistening in the moonlight five miles away, and towering over the tops of the highest eucalyptus of them all.

Undeterred by the grim terrors of an Australian forest at night the indescribable sense of human solitude, the strange, unaccountable sounds that are borne to the startled ear, and the ghostly shapes which imagination sees lurking behind or passing swiftly amongst the trees, she holds on her perilous way, and now at last she is nearing the end of that awful journey. She is within the shadow of that solitary peak which had been to her and to him, a refuge for half-a-year. What had happened during her absence? She pauses and breathes a prayer to Heaven for strength to hear and to bear the worst. Then she hastens to the spot where she had alighted in her descent from the cave a few hours before. She looks up, listens intently, hut can bear no sound from above. The hopeful thought flashes through her mind that he also has descended successfully and would rejoin her, as he had promised, in the morning. Then she remembers the lower chamber of the peak, and with beating heart she proceeds to ascertain whether there is any news in that quarter. With the utmost caution she approaches the entrance, she gives one glance into the interior, and that is all. A wild shriek echoes through the forest, and a woman falls insensible to the earth. For the lantern within had revealed to her the recumbent form of her husband rigid in death. In addition to the bodies of the bushranger and the unfortunate man who was killed in the encounter, the police brought in to Melbourne on that Christmas morning the seemingly lifeless form of a young, sad faced woman, whose agonising cry had so terrified them on the previous night. Under medical treatment she regained consciousness in a few days, but she was not the same Alice as before. The shock had unseated her reason; she was declared unfit to be at large; no one could be found who knew anything of her history, or who would undertake to look after her, and so she was sent to an asylum for the insane.

Twenty years have come and gone, and Christmas is once again at hand. In the lapse of two decades Glenmore has become a more conspicuous object than ever in the landscape, and time has but gently touched its warm-hearted master and mistress. But there are now two additional members of the household. That well-favoured, thoughtful young man reading at his ease on the verandah is the only child of Ormond Gray, but who is his fair companion, that white-robed, nice-looking example of budding womanhood by his side? He calls her “Ella,” and with perfect propriety, for she is the same little Ella whose infancy was so strange and so troubled. Great was the surprise of Ormond Gray and his wife when, on that Christmas morning long ago, they found the little infant under their roof alone, whilst the mother had disappeared without leaving a trace behind. Nor in all the long years that had since elapsed did they receive any tidings of the mysterious, sad-faced woman with the baby in her arms, who came to their homestead, from they knew not where, at the close of that hot summer’s day. But they conceived an ardent affection for the lonely little innocent so unexpectedly left on their hands; they rejoiced in her growing girlhood, and in the development of her good qualities of head and heart; and she became to them as the recognised daughter of their house. And soon she was to become their daughter in a still nearer and dearer sense, for her life was about to be linked with that of their only son, Clement. When that happy event did take place in the course of a few months, the young couple received, as a wedding gift, from the generous Ormond Gray, a branch station of his own, some forty miles away.

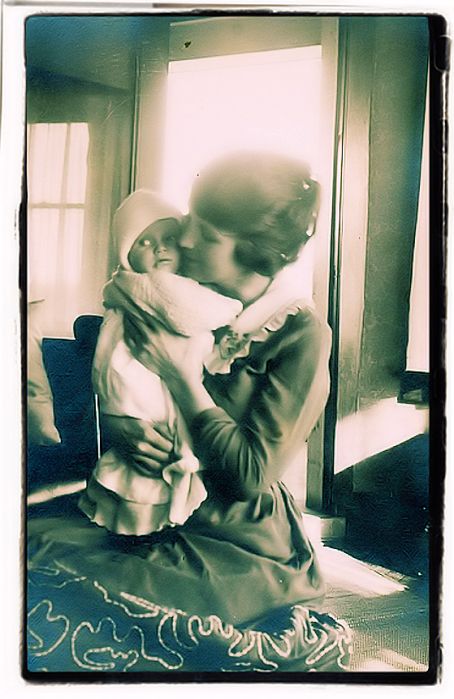

One morning, not long after her marriage, Ella received an urgent message to come across to Glenmore, and when she arrived at her old home she was met by her good foster-mother with a sympathetic smile, and told to prepare herself for a surprising piece of news. By slow degrees she was allowed to learn that her own natural mother, whom she had mourned as gone from earth for ever, was alive and under that very roof. The meeting between the long-separated Alice and Ella was a most affecting one. The white haired but still young-featured Alice had, after many years’ darkness of mind, recovered her reason, but her memory was a blank. Only two words relating to the past could she pronounce – “Ella” and “Glenmore” – and it was their association that led to her timely recognition, and her subsequent happy restoration to a daughter’s arms. Well, indeed, for all that the recollection of that terrible time in the forest had been providentially erased from the tablets of her brain, and that the evening of an agitated life was not clouded by the shadows of the past.

To read other stories you can download this book:

An Australian Christmas collection: stories, sketches, essays. James Francis Hogan

James Francis Hogan (1855-1924), teacher, journalist, author and politician, was born on 29 December 1855 near Nenagh, County Tipperary, Ireland, the only son and younger child of Rody Hogan and Mary, farm workers. The family migrated to Melbourne in the Atalanta in 1856 and settled in Geelong. He contemplated taking religious orders but in 1872 turned to teaching after passing his examination through the Victorian Education Department. Near Geelong he taught first at Anakie, then at Flinders school and in 1877-81 was headmaster of St Mary’s.

While teaching Hogan contributed to newspapers and journals and the success of his work inspired him to become a professional writer. In 1881 Hogan abandoned teaching, went to Melbourne, became sub-editor of the Victorian Review and soon joined the Argus. He continued to contribute to a variety of papers and maintained an active association with Irish-Catholic movements. In 1887 he went to England seeking a wider field for his writing. In London he published his best-known work, The Irish in Australia (1887), which ran to three editions. Hogan contributed to many journals and became recognized as an authority on Australian affairs. His larger works published in London included The Australian in London and America (1889), The Lost Explorer (1890), The Convict King… Jorgen Jorgenson (1891), Robert Lowe, Viscount Sherbrooke (1893), The Sister Dominions (1896) and The Gladstone Colony (1898).

In 1893 Hogan gained pre-selection for the middle division of Tipperary and on 26 February was elected unopposed to the House of Commons. As a member of parliament till 1900 he took a stand as an Irish Nationalist, supporting the government of Ireland bill. Colonial affairs were the subject of his other parliamentary interests and he acted as secretary of the Colonial Party, an unofficial grouping of British parliamentarians who had had first-hand experience in some part of the colonial empire. Hogan returned to Australia only once, for the inauguration of the Commonwealth in 1901. He then returned to England where he lived quietly until his death in London on 9 November 1924. He never married and was survived by his sister Margaret.

While Hogan’s career was marked by dedication, his achievements were small and marginal in their effect. Single-minded and steadfast, he had a rigid personal morality and a strong conception of the responsibilities of citizenship. As a writer Hogan was a conscientious and competent journalist but his creative work was not outstanding.

John R. Thompson Australian Dictionary of Biography

Read also our other posts on Christmas

Christmas markets in England ;

Christmas markets in America ;

Christmas markets in Italy and Germany ;

Traditional Christmas Carols ;