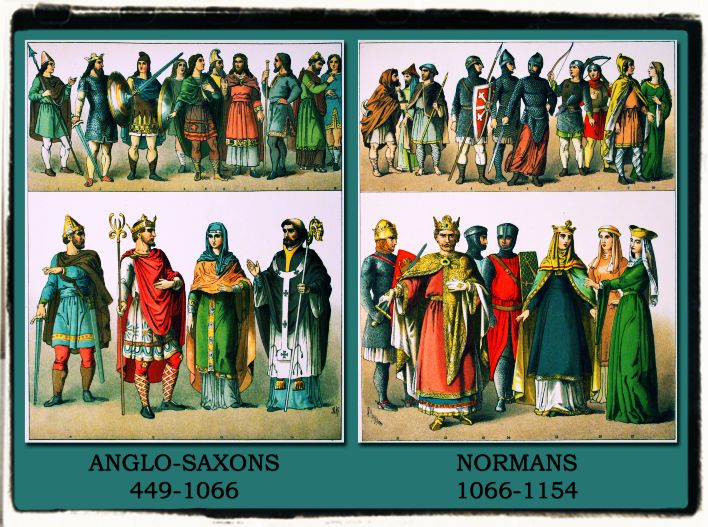

![]() From The Anglo-Saxons, Through The Normans, To The Origin Of English Parliament

From The Anglo-Saxons, Through The Normans, To The Origin Of English Parliament

The Anglo-Saxon asserted themselves gradually, the conquest was brought to conclusion in 613 when the chief of the Angles, Etelfrith, defeated and submitted the last defenders of Chester. The Anglo-Saxons formed the so called “Heptarchy”, and the country was divided into seven kingdoms: WEssex, Sussex, Kent, Essex, East Anglia, Mercia, and Northumbria. Some of these kingdoms survive nowadeays in the names of English modern counties. Each kingdom was ruled by a king elected by the Witan, a council composed of the dignitaries of the State and the Church. The national unity was preserved by the institution of a “Bretwalda” to act as overlord over the kingdoms and its rulers.

Long internal struggles among these kingdoms and recurrent raids from Scandinavian peoples characterized the subsequent years, and contributed in strengthening the rank of Warriors (thanes). Even before the Anglo-Saxons came to Britain their tribal organization was disintegrating. But the first townships, assembling people without any link of kinship arose. The trend toward a new social organization increased around 700 A.D., private property began to take shape with King’s grants, and the authority of the State grew in importance.

The Normans belonged to the stock of Scandinavian peoples, whose development was mainly due to the use of the large iron axe. About 700 A.D. they spread along the coast of Norway and began to clear forests and build ships, which enabled them to make considerable voyages. A part of this adventurous people reached France and obtained by the Frankish kings the concession of the land, now known as Normandy. They came to Britain because the English king Edward the Confessor (1042-1066) had promised William Duke of Normandy, his distant cousin, to recognize him as his lawful heir. But, on Edward’s death, the Witan proclaimed king of England Harold of Wessex. William denounced him as an usurper, and to enforce his claim to the throne, he assembled an army and invaded England. The unfortunate king Harold was defeated and killed at Hastings (October 1066). Then William found a weak opposition and the last bulk of resistance, assembled in London, was easily won by his troops, and on Christmas day of 1066, he was crowned king of England in Westmister Abbey.

The Normans brought with them a body of laws which gave a new asset to the country: Feudalism which, though was taking shape before the conquest, was fully established in England. It consisted in a downward delegation of power; the king as the only owner of the land, granted part of it to his followers in return for services in war, or other customary dues. The Vassals receive, together with the lands, also the political right of governing them. They, in their turn, subdivided them among others on similar terms and that formed a sort of pyramid, that is a feudal hierarchy.

The Barons held their lands from the King, and were obliged to follow him in battle with a fixed number of knights; the Knights held lands from the Barons, and were to follow them for forty days a year, or for longer periods if necessary. The feudal relation passed from father to son. Below the knights came the peasants, who were serfs bound to the soil and to the lord of the soil. The administrative officers were called Sheriffs. The Barons constitued the Royal Consilium or Curia, i.e. the adsvisers of the King. The new military system and the strict feudal order proved much heavier than the mild yoke of the last Danish and Saxons kings.

As Feudalism was imposed in England deliberately from above, it developed in a more complete and regular way, than in other European countries. For the first time a strong central power was created, which afterw2ards met oppositions above all from the Barons. Williamjk the Conqueror is regarded as one of the most outstanding figures of the MIddle Ages, for his military genius and his wise policy. During his reign the “Domesday Book” was drawn up, a survey of the economic resources of the country and their distribution. The Book is still important nowadays, because of the accurate picture it gives of the period.

William’s successors: William II and Henry I continued to strengthen the power of the state. Henry II (1154- 1189) who had married Eleanor of Aquitaine was one of the most powerful kings of the time. His kingdom extended from tghe Scottish borders to the south of France, even if his continental possessions were held by the king of France in a feudal tenure, he was in effect their absolute ruler. Henry II improved the State machinery by establishing the “Curia Regis” to deal with the day to day affairs; special affairs were dealt with by the “Council” from which Parliament developed later on. Henry carried on important financial and judicial reforms.

When he attempted to try members of the clergy in the royal courts, the Church claimed the right to try them in its ecclesiastical courts. The Church, which had in those times gained great advantages and power, aimed at being recognized as independent. It was part of a wider movement investing all European countries, known as the Investiture Struggle. Richard I Lionhearted (1189-1199) son of Henry II succeeded himj. He was an adventurous king, who preferred the pursuit of fame and glory to the affairs of the State. Together with other European monarchs he took an active share in the Third Crusade to recapture the Holy Places from the Moslem invaders.

The short reign of Richard was a time of important development in the framework of the Feudal system. The bi-national character of kings and barons had favoured trade between England and France: iron, tin, salt, spices, wine and above all clothes, were i9mported from Flanders and Gascony. With the flourishing of trade money became the normal system of payment and replaced the old duties in kind and services; a process which was called “commutation”. Moreover Richard’s need of money to equip his army induced him to extend the selling of Charter to towns: through paying a sum of m oney they freed themselves from their obligations.

This brought out the rise of chartered towns freed from personal relations and services and contributed to the formation of new classes. At Richard’s sudden death in 1199, his brother John Lackland became king of England. He commited every sort of abuses by imposing excessive taxes and confiscating the estates of his vassals without a judgement. The Church was treated in the same way and the result was the complete isolation of the crown. John’s foreign policy proved equally unhappy. His refusal to accept William Laughton as Archbishop of Canterbury, involved him in a new dispute with Pope Innocent III, who excommunicated him and persuaded the Kings opf France and Scotland to make war on him.

John’s forces were defeated at Bouvines (1214) and William Laughton became the leader of the baronial revol, and in June 1215, John was forced to accept the programme embodied in the “Magna Charta Libertatum”. The document contained sixty-three clauses concedrning feudal obligations, the rights of the State and the Church, justice and taxation, and prevented further unlawful practices, by setting up a permanent committee of twenty four barons. The Charter was a turning point in English history, but its importance has often been exaggerated; it didn’t guarantee democratic rights and parliamentary government, as Parliament did not exist. But it paved the way for the entry of new classes into the political field. During the reign of John’s son, Henry III, the principles of the Charter were not observed. opposition came first from the Barons and in 1227 a special committee responsible to the Council for the detailed carrying on of the Government, was set up. It was the first step to transform the Council into Parliament.

When Henry tried to split among the Barons,l the cdountry plunged into civil war and the group who opposed him, led by Simonm de Montfort, defeated him at Lewes in 1264. Then the movement against the Crown assumed a more popular character, including lower classes such as merchants and lesser landoweners. In the next year, Simon de Montfort summoned to his Parliament the representatives of the shires, cities and boroughs besides the normal members of the Council. In the same year Simon de Montfort was defeated and killed in the battle of Evesham by Henry’s son Edward I. But his cause was not completely lost, for the new king found it wise to adopt many of the changes proposed by the rebels and Parliament assumed a permanent form.