Christianization of Britain. The influence of Christian missionaries and priests in England has been significant for the development of the English language. The arrival of Christianity in England brought with it a new written language and literature, which helped to standardize and develop the English language and culture, starting to form the strong character of the future European Culture.

The Roman invasion of Britain, which began in 43 AD and lasted for several centuries, had a significant influence on the local language of the British Isles. Before the invasion, the inhabitants of Britain spoke a variety of Celtic languages, including Welsh, Cornish, and Breton. However, with the arrival of the Romans, Latin began to have a growing influence on the local language.

One of the most significant ways in which Latin influenced the local language was through the introduction of new vocabulary. The Romans brought with them a variety of new words, particularly those related to the military, government, and administration. Many of these Latin words were adopted into the local language and continue to be used in modern English today, such as “camp”, “fort”, “road”, “wall”, and “mile”.

In addition to vocabulary, Latin also influenced the grammar and syntax of the local language. Latin had a strong influence on the development of Old English, the language spoken in Britain after the withdrawal of the Romans in the 5th century. Latin grammar and syntax influenced the development of Old English grammar, particularly in the areas of sentence structure and word order.

Overall, the Roman invasion of Britain had a lasting influence on the local language, with Latin becoming an important part of the linguistic landscape. The influence of Latin can still be seen in many aspects of the English language today, particularly in the vocabulary and grammar of scientific and academic fields.

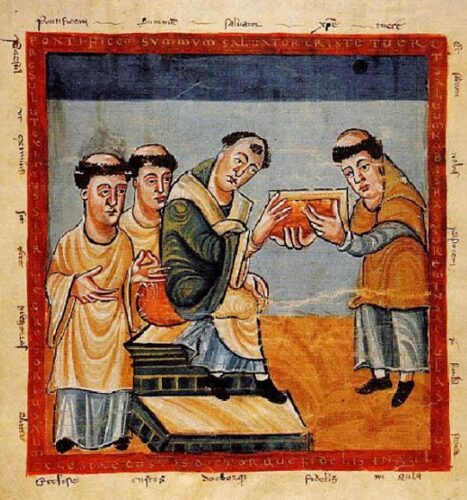

One of the most significant events in the history of the Christian diffusion of Latin in Great Britain was the arrival of St. Augustine in the year 597. Augustine was sent by Pope Gregory I to convert the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity and establish a church in England. As part of this mission, he brought with him a knowledge of Latin and began to translate Christian texts into Old English, which helped to spread literacy and establish a written tradition in the English language.

Over the next several centuries, Christian missionaries and priests continued to play a key role in the development of the English language. They established monasteries and schools, where they taught Latin and the Bible, and produced written works that helped to standardize the English language. In the 10th century, King Alfred the Great commissioned the translation of several Latin works into Old English, including the famous Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which helped to preserve the history of England in the English language.

Throughout the Middle Ages, Latin continued to be the language of the Church, and many religious texts and documents were written in Latin. However, as the English language evolved, Latin began to have a greater influence on English vocabulary and grammar. Many Latin words and phrases were adopted into the English language, and the grammar of Latin also influenced the structure of English sentences.

In summary, the influence of Christian missionaries and priests in England was significant for the development of the English language. They brought with them a knowledge of Latin and established a written tradition that helped to standardize and develop the English language. Some key historic events connected with the Christian diffusion of Latin in Great Britain include the arrival of St. Augustine in 597, the establishment of monasteries and schools, and the translation of Latin works into Old English.

But now let’s analyze in a deep manner what exactly happened and the results of the spread of the Latin culture on the English language and society. The Germanic tribes that emigrated to the island had not yet been reached by the preaching of the gospel. Their religion is known to us through the description that Tacitus makes of it in his Germania and the names of some of their gods have remained in the language replacing, in the days of the week, more or less corresponding names of Roman deities: Tiw (for Mars) in Tuesday , Woden (for Mercury), better known by us as Odin, in Wednesday, Thunor (for Jupiter) in Thursday. Another goddess, Eostre, would have given, according to Bede, the name to a spring festival, later replaced by the Christian Easter, Easter.

Christianity had expressed a missionary of exceptional value in Patrick, son of a decurion from Roman Britain. He went among the Scots, the Celts of Ireland, and with a prodigious activity he brought the island to the Christian faith within thirty years (432-461), implanting structures centered on the monastery, respecting, in a certain sense, the organization of the clan, unlike the continental communities which grew up around the bishop in the urban centers. But none of these Welsh Christians moved towards the Anglo-Saxons, for, as Trevelyan wittily notes, “the Welsh Christians still hated the Saxon intruder too much to try to save his soul from him”.

From Ireland, after stormy events at home, Columba left in 563, a member of the royal family, who embarked with twelve companions and landed at Iona, an island off the western coast of Scotland: here he founded a monastery which became a important center of evangelization and culture together. From here the missionaries moved towards Scotland and the Hebrides to bring the Gospel to the Picts of the north: the monk Niniano had taken care of those of the south almost two centuries earlier, founding the monastery of Candida Casa (Whithorn) in Galloway. Columba died in 597.

In the same year a group of forty monks who had come from Rome on the mandate of Pope Gregory the Great landed on the island of Thanet in Kent with the mission of preaching the Gospel to the Angles. They were led by Augustine who, using Frankish interpreters, converted King Ethelbert. The success was favored by the presence at court of the Frankish queen Berta, who was already a Christian. Accompanying the princess of Kent Ethelburga, who was marrying Elwin, to the court of Northumbria, the monk Paulinus converted and baptized the king himself and many notables at Easter 627. He would then become archbishop of York, as Augustine had become of Canterbury.

In 633 Edwin is killed in battle by Penda and Cadwallon. Paulinus flees south and Northumbrian Christianity is in danger of rapidly disappearing. The following year, however, a son of Edwin’s predecessor, Oswald of Bernicia educated on Iona, regained the throne. The king has Bishop Aidan come from Iona, a holy monk who walks through the lands of Northumbria preaching the gospel, having as interpreter Oswald himself who in the long years of exile (his father had been dethroned by Edwin) had learned the language of the Scots (cf. Bede, Hist., III, 3).

Aidanus established the center of his activity at the monastery of Lindisfarne, on the east coast of Scotland, on a rocky promontory near Oswald Castle at Bamburgh. From here the mission radiated towards the center and south of England, especially after in 653 Penda, the pagan king of Mercia, had opened his lands to four priests who had come from Lindisfame. One of these, Cedd, went as far as Essex, a territory of East Anglia, and his brother Chad became bishop first of York, and then of Lichfield, the capital of Mercia.

Meanwhile another Roman mission sent by Pope Honorius and placed under the guidance of the monk Birino had arrived in Wessex in 633 establishing an episcopal see in Dorchester. Towards the middle of the seventh century almost the whole island had been reached by Christian preaching: Sussex and the Isle of Wight remained outside, which perhaps proves the scarce missionary zeal of the community founded by Augustine in Kent, surprising if one compare with the evangelical fervor of the communities of Celtic origin. The English church, however, was far from being united: the Irish mission and the Roman mission had created two types of church, different in rites and customs, the first basically monastic, the second centered around the bishop.

The conflict over the date of Easter was the reason that triggered the conflict. A synod convened at Whitby in 663 marks the triumph of the Roman party, led by the monk Wilfred. This choice brought the English church into close contact with continental Christianity and monasticism of the Benedictine type, but we must not forget that the formation of the tradition of written English coincides with the full splendor of Northumbrian Christianity of the Celtic type (sec. VII- VIII): from here came, for example, the use of the Latin alphabet to replace the runes by the English.

The task of organizing English Christendom into unity fell to a curious trio of men from Rome. In 669 the pope sent as archbishop of Canterbury a monk from Asia Minor, Theodore of Tarsus, then 66 years old: he brought with him Hadrian, a native of North Africa, and Benedict Biscop, an Englishman educated in Rome. Theodore succeeded, with a series of synods, in giving unity and solidity to the English church, Hadrian taught school in Canterbury, Benedict Biscop founded the monasteries of Wearmouth (674) and Jarrow (685) in the north, supplying them with books that he brought back with him from his numerous trips to Rome: here Bede will find the ideal conditions for studying and writing.

Faith and Latin thus become a unifying factor in the mosaic of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, and in this period British culture offers Europe three leading figures: Aldelmo of Malmesbury (c. 639-709), Bede of Jarrow (673- 735) and Alcuin of York (735-804). The first is the author of treatises in Latin, but it is known that he did not disdain to sing songs in the Saxon language to attract people to preaching; Bede is the author of many works in Latin that had a profound influence on medieval culture, but he is above all the historian par excellence of the origins of the English nation; Alcuin will make such an impression on Charlemagne that the emperor will call him to organize the reform of studies, and in particular the palatine school in Aachen.

Two elements deserve to be noted in this series of events: 1) the monastic character of English Christianity, and therefore its rich cultural substance; 2) the harmony and understanding with which the ecclesiastical and civil authorities work. Only in this way can a figure like that of King Alfred be explained on the one hand, and the achievement with Alfred’s dialect, West Saxon, of a sort of standard language: the monastic cultural centers and their “scriptoria” had the support of the royal authority, also worked in his service, and thus inevitably became a pole of attraction.

On the “linguistic” consequences of the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity it is worth mentioning what Barbara M.H. Strang writes in her History of English (1970): “Linguistically the effects of this (the conversion) can hardly be overestimated. The world of letters accompanied the new religion it transformed what the English had to talk about, how they talked about it, and their capacity to keep records from which we can recover information on all aspects of their life.Less obvious, but linguistically relevant, is the organization of the Church on a basis by which the English were treated as a single and distinct people; they became a unity in religious organization long before they constituted one politically”.

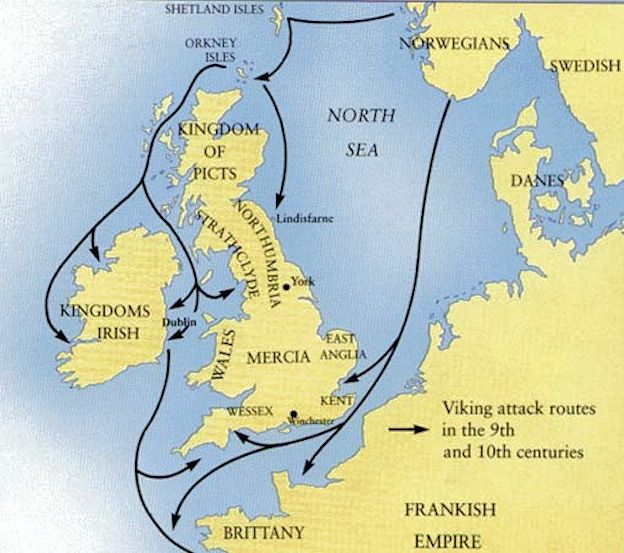

Due to the Viking threat to the north, three great centers of monasticism were sacked and burned one after the other: Lindisfarne in 793, Jarrow in 794, Iona in 795. The very location of these monasteries built on the coast or on nearby islands proof that no one expected a threat from the sea. The first attacks were seasonal raids: people came to spend the winter in England, and the penetration did not exceed 15 miles. The success was due to the fact that the British had neither fleet nor coastal defence.

But a large Danish army instead landed in 865 in East Anglia with the clear intention of conquering the territory. The Great Heathen Army was a Viking force primarily comprised of Danish warriors, though it also included Norse and Swedish fighters. In 865, the Great Heathen Army, led by the legendary Danish chieftains Ivar the Boneless, Halfdan Ragnarsson, and Ubbe Ragnarsson, launched a large-scale invasion of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England. The invasion marked the beginning of a series of Viking incursions and campaigns that lasted for several decades.

The Great Heathen Army’s arrival in England was met with resistance from the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, which included Wessex, Mercia, Northumbria, and East Anglia. Over the course of their campaigns, the Vikings captured and established control over various territories, including York (then known as Jorvik), East Anglia, and parts of Mercia. Their invasion had a significant impact on the political and cultural landscape of England. It led to the decline of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, weakened their power, and ultimately paved the way for the establishment of the Danelaw – a region in which Danish law and customs held sway.

The Viking invasions of England continued for many years, with subsequent waves of Viking armies arriving from Scandinavia. It wasn’t until the 10th century that the tide began to turn in favor of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, eventually leading to the reconquest of the Danelaw and the consolidation of England under the rule of King Æthelstan in 927.

15 years after the arrival of the great army, all of central and northern England, from the Thames to the Tees, is in Danish hands. Wessex remains the only English kingdom and its king can be the spokesman for the entire Anglo-Saxon world. Thus it comes about that, paradoxically, the result of the Danish invasion is the rise of an “English” consciousness personified in the West Saxon monarchy and the decisive supermanage of the splitting up of the ancient Germanic tribes. This might not have happened without the presence on the throne of Wessex of the best man in all of its history: Alfred the Great.

After the victory over Guthrum, King Alfred consolidated his success by starting the construction of a fleet and having fortresses built, reusing, where they still existed, the ancient Roman walls, such as in Bath, Exeter, Porchester, Winchester and Chicester. London is occupied in 886, and the conquest ends what might be called the “military” period of Alfred’s reign.

Once the Viking storm had passed and the borders of his kingdom were consolidated with the treaty of Wemore (879), Alfredo devoted himself to a work that would alone be enough to justify the title of “great” that history has always recognized him: the reorganization of studies. The aim was to revive culture among free young people and members of the clergy, the result was the production of a literature in the vernacular that has no equal in Europe at the time. It is the same king who devotes himself to the study of Latin, and who translates and has translated works which he considers fundamental for the formation of a minimum cultural baggage.

These works are: the Cura Pastoralis and the Dialogi Miracolorum of Gregory the Great, the Soliloquia of St. Augustine, the De Consolatione Philosophiae of Boethius, the Historiae Adversus Paganos of Paolo Orosio, and the Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum of the venerable Bede. In a letter sent to his bishops together with the gift of a copy pastralis, Alfredo notes the miserable state of studies in the England of his time and gives the reasons for his translation project. The remedy suggested by Alfredo is twofold: 1) the translation of the books that it is most necessary to know; 2) the study of Latin for those entering the ecclesiastical state.

It is very probable that the suggestion of Charlemagne’s example acted on him. Like the emperor, he also asked for foreign aid, and from the Franks came Grimbold, from Flanders, while from Lower Germany came John, a Saxon priest. But, confirming that not all was lost in England either, we find among Alfredo’s collaborators a Welshman, Asser, and a small group of Mercians, such as Plegmund, who was to become archbishop of Canterbury, Werferth, the translator of the Dialogues, who was to become bishop of Worcester, and two priests, Athelstan and Werwulf. This suggests that in south-western Mercia, the corner of England that had suffered least from the Danish invasion, the great English cultural tradition had been preserved, especially around Malmesbury Abbey, an Irish foundation already illustrated by the great figure by Aldelmo.

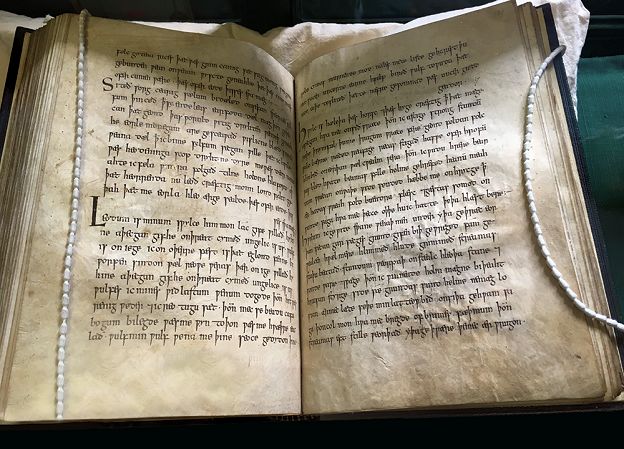

It may be that Alfredo’s first intention was to restore the study of Latin, using English only as the first stage in cultural formation. In fact, his reform brought the language of the Anglo-Saxons to a high degree of prestige, to the point that the same annals of the kingdom, unlike what happened on the continent and previously also in England itself (it is known of annals drawn up in York in Latin in the 8th century), were written in the vernacular. It is from Alfred’s time that the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle becomes a rather detailed account of contemporary events, and, as P.H. Blair, its value lies precisely “in the use of the vernacular in preference to Latin.

In addition to being a historical source of the highest importance, it supplies invaluable evidence for the development of the Old English Language”. Seven manuscripts of the Chronicle exist today, of which the most important are: manuscript A commonly known as the Parker Chronicie (from the name of Matthew Parker, archbishop of Canterbury, who was its owner for a certain time), which goes up to 1070. and manuscript E, or Peterborough Chronicle (after the abbey where it was written), which proceeds to 1154, well beyond the Norman conquest.

With the reign of Alfred’s son, Edward the Elder (899-924), the reoccupation of the territories conquered by the Danes, the Danelaw, began. Within three years, from 917 to 920, the king of Wessex managed to bring his frontier up to the river Humber, after having conquered the great Danish fortresses of the Five Boroughs: in Bakewell (Derbyshire) Edward received homage and submission of all the various kings who rule the island. At the same time a new Viking attack leads the Norwegians, who already occupied part of Ireland, to settle in the Wirral, gradually occupying the coastal strip from Chester to Carlisle.

The English advance north continued under the reign of Edward’s son Athelstan, who occupied York and attacked a coalition of Norse rulers including Olaf, Norse governor of Dublin, Constantine, king of the Scots, and the king of Strathclyde. The English win a decisive battle at Brunanburh (937), an event which also had a literary celebration in an Anglo-Saxon poem. The events of three quarters of a century (865-937) completely destroyed the old system of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms: an English monarchy emerged, and with the reign of Edgar (959-75), solemnly consecrated in Bath in 973, we witness the most splendid period of Anglo-Saxon culture, propitiated and favored, as well as by the achieved political peace, by an extensive and profound monastic revival.

The renewal had started from the continent with the foundation of Cluny, in Burgundy, in 910, and the English reform of the monasteries passed through contacts with two abbeys that had already entered the area of Cluniac influence: Ghent, in Flanders, and Fleury-sur-Loire , in central France. Dunstan, a monk of Glastonbu-ry, spent two years in exile in Ghent and was appointed archbishop of Canterbury in 959. Oswald, of Danish origin, was sent to Fleury, who on his return to England himself would be nominated 959 archbishop of Worcester and then of York. In the same French abbey a friend of Dunstan, Æthelwold, abbot of Abingdon, sends one of his monks to learn the new customs: in 963 Æthelwold is elevated to the archbishopric of Winchester.

With three monastic-trained bishops at the head of the most important dioceses of the kingdom, and with the ardent and enthusiastic support of King Edgar, the reform had the best guarantees of success. Ancient monasteries are restored, and new ones are founded in the West Midlands and East Anglia, where the renovated abbeys of Peterbo-rough (966), Ely (970) and Thorney (972) will prove strong enough to resist the second great Scandinavian attack which will bring a Danish king to the throne of England. The demand for books greatly increased and the scriptoria worked with alacrity, in contact with the great abbeys of the continent.

What matters most for our story is that the monastic reform translates, in the tradition begun by King Alfred, into a series of “aids” for monks and priests which are either versions from Latin, such as the Benedictine rule made by Æthelwold himself , or original productions of homilies and saints’ lives which show what a level of excellence Anglo-Saxon prose had arrived at. It is also noteworthy that this work is not limited to homiletic or devotional literature, but also includes the recording and preservation of the great Old English poetic production: it is certainly no coincidence that they belong to this period, the end of the tenth century , the four great codices that contain the majority of Anglo-Saxon poetry: the Beowulf, the Junius Manuscript, the Exeter Book and the Vercelli Book.

The literary tradition that began with the Alfredian versions, the area of origin of at least two of the great reformers, the active part of the king and the court in the renewal of the studies result in the elevation of West Saxon to a standard language status. Dialects are not dead: in the north, in the abbeys of Northumbria, the Gospels are glossed in the local language and according to different criteria from those followed in the south, preferring, for example, the semantic calque to the Latin loan.

The poetic texts themselves, which show a discreet presence of Anglic forms, indicate that poetry must have preferred as its own means of expression the language of the Midlands, which could have a wider range of understanding, constituting a sort of bridge between the more diverging dialects of north and south. However, it remains that from Wessex come the textbooks for schools, the legal documents, the materials of official production to be incorporated into the local chronicles, and it is therefore the language of Wessex that becomes the literary language of England.

However, the spoken languages remain diversified: the same graphic inconsistencies that appear in the documents reveal that the scribes probably had to deal with a language that did not exactly coincide with the English spoken by them. The very rapid disappearance of this literary language in the aftermath of the Norman conquest demonstrates its artificiality and the persistence, under this cloak of apparent uniformity, of the varieties of spoken dialects. These observations have only the purpose of keeping the spoken language distinct from the written one, and in no way aim at diminishing the value of a success which, as has already been said, was unique in Europe at the time: the creation of a vernacular literary language certainly not inferior to the then prevailing Latin.

At this point we must certainly recall the fruit and best expression of the monastic reform, Aelfric (c. 955-1020). Brought up in Winchester at the school of Æthelwold, he first became master of the monks at Cerne Abbas (Dorset), where around 990 he wrote the two series of Catholic Homilies; in 1005 he was appointed abbot of Eynsham, near Oxford, and remained there until the end of his days. His work, born mostly to respond to needs of a practical nature, constitutes a small library by itself. In addition to the two series of homilies for the liturgical year, Aelfric wrote a third dedicated to the lives of the saints.

He also put himself at the service of bishops who commissioned him pastoral letters. For a noble layman he translated the first seven books of the Bible, the Heptateuch, and for another he wrote a treatise on the Old and New Testaments: the existence of such readers shows that the cultural renewal had achieved beneficial effects even outside of monasteries. Finally, the result of his activity as a professor are a Latin Grammar, a Latin-English Glossary and the Colloquium, a sort of conversation manual, with dialogues between various characters representing the different trades.

The use of rhythm and alliteration give Aelfric’s writing a truly remarkable height of style, and W.P. is right. Ker to define the abbot of Eynsham “the great master of prose in all its forms”. These qualities, together with the particular correspondence of the contents to pastoral and monastic needs, guaranteed success and long life to Aelfric’s writings, which continued to be copied up to the middle of the thirteenth century, constituting a fundamental point of reference for the rebirth of middle religious prose -English. Various collections of homilies belong to this splendid literary season, among which those of Wulfstan, archbishop of York, excel. The West Saxon version of the four gospels is from the early 1000s, and will continue to be copied even after the Norman conquest. Attempts are also made at “scientific” prose, as documented by the work of Byrthferth, a monk of Ramsey, who wrote a Manual explaining the rudiments of astronomy and mathematics for the rural clergy.

Poetry is absent from this movement of cultural renewal: the very copying of the four great codes is defined by D. Pearsall as “an offshoot of the revival”, “act of homage to the past”. But if poetry is moribund, prose is vigorous and it is probably to the great revival of studies in the monasteries that we owe the survival of English as a literary language beyond the disasters caused by the arrival of the Normans. Unfortunately, the cultural flourishing of the last years of the tenth century did not correspond to an equally flourishing political situation. The Danes attack the island again with armies of professional warriors who certainly don’t come to settle on richer lands to cultivate them. And people who make war their job, and who don’t hesitate to kill and massacre.

The English resistance cannot do much and the island thus becomes a simple province of the great Scandinavian empire which also includes Denmark and Norway. Under Canute the Danish and the English elements are united: it can be thought that a movement of convergence between the two languages is thus strengthened (to which the Norwegian of the Vikings settled in the west should be added, as already mentioned), which in at that time they were still quite close. A Scandinavian linguistic presence is not detectable in the Old English texts we possess because the Danes and Norse did not write their own language, except with runes in short texts, and because the literary language of this period was, as has been said, West Saxon.

With the reign of Canute, however, the premises for future troubles also arise. The territory is divided into four large counties (earldoms): Wessex, Mercia, East Anglia and Northumbria. The leaders of these lands (earls) grow more and more in importance and come to fight among themselves and against the king, not disdaining to seek support abroad, above all in the direction of Scandinavia where the various kings who succeed each other look with sympathy to a possible reconquest of the island, especially since, with Edward the Confessor (1042-1066), the Anglo-Saxon dynasty of Wessex returns to occupy the throne.

Edward, son of Æthelred, had spent twenty-five years of exile in Normandy, in the midst of other Vikings who, however, had in the meantime completely Frenchised. He returns to England almost as a foreigner, bringing a certain number of Normans with him to court, naming Robert of Jumièges archbishop of Canterbury, and two other priests called from France to the sees of London and Dorchester. The great counts, especially Godwin of Wessex, clash in constant struggles, and the Norwegian fleet sails menacingly in the Irish Sea. Edward takes less and less interest in the affairs of the kingdom, has no children, and even promises his friend William of Normandy to leave him heir to the throne upon his death.

When Edward disappears in January 1066, the English nobility appoints Harold, son of Godwin, who with his exploits was already in practice the military leader of the kingdom, having fought successfully against the Welsh and Scandinavians. Harold must immediately face an attack that is moved by his brother Tostig in alliance with the king of Norway Harold Hardrada. The two are defeated and killed at Stamford Bridge, in North Umbria, at the end of September. Two days after this victory, William of Normandy’s army arrives at Pevensey to claim the throne of England. Harold has to rush south. The clash takes place in Hastings, on October 14, and William has the upper hand, exploiting above all the greater freshness of his troops and the cavalry. The king and much of the Anglo-Saxon nobility lose their lives in battle. For England, and for the English, a new era thus begins.

You can also read the following articles:

Latin influence on the English language

The Latin Language, a short history

English, Greek and Latin, a complete article

English Renaissance, the revival of learning

Short History of the English Language

The essence of English Grammar

Short History of the Origin of English

English words origin and vocabulary

History-of-the-English-Language.pdf

British-history-milestones-synthesis

Questions-about-the-english-language

History-of-English-Literature-Summaries.pdf

British_literature_history_chart_summary.htm

General_literature_history_chart_summary.htm