On investing story, a short revealing text from the book by John Neff On Investing that explains the secrets and the rules of safe and profitable investing art.

My whole career, I have argued with the stock market. Happily, as the Windsor Fund’s record shows, I won more arguments with the market than I lost.

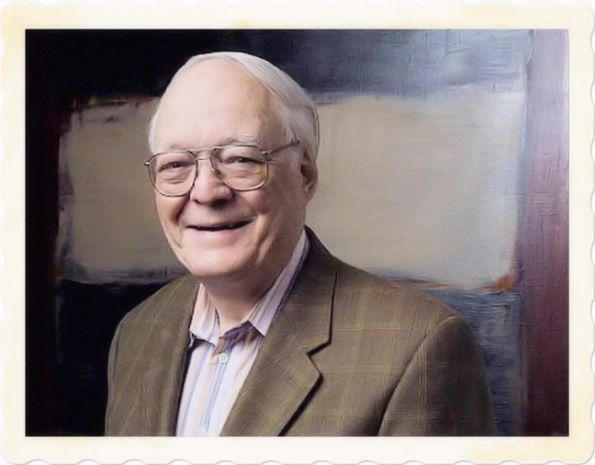

John Neff

John Neff is the investment profession’s investment professional. Nobody has ever managed a large mutual fund so very well for so very long a time. And no one is likely to do so ever again. The record of his management of the Windsor Fund for more than 30 years is truly astounding. During an era when professional investment managers returns have increasingly lagged the market averages, John Neff delivered an annual average that exceeded the “market” rate of return by more than 3 percent. (His results were actually 3.5 percent ahead of the market. After expenses, the net rate of return, over one-third of a century, averaged 3.15 percent higher than the market year after year after year.)

Consider what his record really means, given the great effect of compounding (which Albert Einstein regarded as one of humanity’s most enlightened ideas). Compounded over 24 years, 3 percent per year will double the original investment. John Neff achieved more than 3 percent for more than 24 years!

Charles D. Ellis

In the spring of 1998, I taught a graduate seminar on investing at the Wharton School in Philadelphia. A very lively group of students sparked extensive reflection on my part. Aspects of my life fell together in answer to dozens of questions about the nature of the investment process and why I chose the path I followed. This book continues my conversation with these students.

A book is a one-sided conversation, to be sure. But, like a good conversation, it can express a point of view in an informal manner, unencumbered by charts and graphs that often clog books on this subject. If we shared a compartment on a long train ride, what you read in these pages is what I’d tell you about investing. I have highlighted the ideas that seem most enduring to me after three decades at Windsor, rather than supply a laundry list of topics related to investing. You can find other books for that.

Teaching invited many questions about my own learning curve. I’m not sure where it began, exactly. I joined the U.S. Navy and studied aviation electronics before I dreamed of trading stocks, much less managing the largest equity mutual fund in the United States – the status Windsor held until the doors were closed to new shareholders in 1985. Perhaps my career started before I learned to count. I was always a stubborn little fellow, which my mother expressed very succinctly: “John Brown,” she declared, “You would argue with a signpost.” She was not only right, she was prescient. My whole career, I have argued with the stock market. Happily, as the Windsor Fund’s record shows, I won more arguments with the market than I lost.

John Neff

A freezing morning, in early January 1955, marked the start of my investment career. Picture a 23-year-old ex-sailor and newly minted college graduate at the Toledo entrance ramp to the just completed Ohio Turnpike, thumbing a ride to New York City. This uncelebrated debut sounds strange nowadays to legions of job candidates seeking prestige and lavish signing bonuses right out of school. No one offered to pay for a bus ticket, much less airfare and a fancy hotel…

I knew more about baseball than about investing. The meager extent of my accumulated market wisdom at that time came from a couple of college classes on the subject. I was neither prepared nor inclined to preach the merits of investing, which probably was just as well. In those days, for most Americans, October 1929 and the Great Depression still chilled impressions of the stock market. The Dow Jones Industrial Average had finally returned to its 1929 highs after twenty-six years. When asked about my purpose, I just said I was going to New York to look for a job.

John Neff

Somehow I acquired a booklet on investing, and long hours of lollygagging between work details gave me plenty of time to peruse it. I read about common stock and preferred stock. Without any indication whether my Aro Equipment stock was common or preferred, I wrote to my father and asked which type I owned. I owned common shares, which, I learned, rise and fall in price with the company’s performance. This was my introduction to the theory and reality of how shareholders garner the lion’s share of potential rewards, as well as the risks of loss.

My nascent interest in stocks marked the earliest sign of my investment career, although the outcome was still far from obvious to me or to anyone else. At the same time, it was abundantly clear that a combination of frequent boredom and tongue-lashing from boatswain mates made a military career untenable. To avoid similar experiences in civilian life, I finally figured out that it was time to give college a try. In this spirit, I enrolled in two correspondence courses offered by the United States Armed Forces Institute, better known as USAFI. My quick grasp of freshman English and an introduction to psychology emboldened me to think I might succeed in college, despite my undistinguished academic track record in high school. One weekend, a buddy and I hitchhiked from Norfolk to nearby William & Mary College, which administered college aptitude tests. The results left little doubt that I could handle college.

John Neff

No one on Wall Street was clamoring for my services in January 1955, so I accepted an offer to join National City Bank in Cleveland. Besides its virtues as Cleveland’s most prominent financial institution, the Bank was a lot closer to Toledo, Lilli’s hometown.

Armed with my native skepticism, the teachings of Sidney Robbins, and a dog-eared copy of The Great Crash, John Kenneth Galbraith’s engaging account of events leading up to the 1929 market meltdown, I marched into the professional investment arena more full of myself than full of ideas. The Bank put me to work as a securities analyst in its Trust Investment Department, a unit formed in the depths of the Depression to safeguard personal and corporate assets against erosion.

John Neff

The majority of extreme losers, it turned out, lent themselves to three generalizations:

1. Almost without exception, faulty company analysis deserved the blame. Fundamental targets were simply missed by extremely large margins.

2. Windsor had not overpaid for anticipated earnings or even current earnings, for that matter. If earnings power had only been maintained, we might have at least retreated without losing money. Our perspective was so poor in this adventure segment that, in most cases, substantial earning power deterioration occurred.

3. We displayed a gratifying ability to realize mistakes and salvage values from situations that subsequently deteriorated, in some cases to the vanishing point. Virtually every elimination of a loser was a good sale.

The mutual funds field has grown more cluttered, but my motto has not changed: Keep It Simple. Toward simplifying Windsor, we narrowed the field of appealing investments into just two broad groups.

1. Growth stocks. These are companies with established and recognized growth characteristics, such as sharply rising demand for their products, modern technology, advanced marketing techniques, scientific orientation, or intensive research programs. They therefore offer above-average, long-term prospects for rising earnings and dividends.

2. Basic industry stocks. These companies afford a broad participation in the long-term growth of the American economy. Carefully selected companies of this character, at certain times, will offer outstanding opportunities for increased income and profits. Also included in this general group are “special situations” companies that are undergoing significant changes in their products, market, or management.

Investment strategies abound for making money in bull markets, bear markets, adrenaline markets, or you-name-it markets. During the nineties alone, investors witnessed nearly every market climate, from doldrums in 1991 to a frenzy for Internet stocks in 1998. A new century will unveil more variations and, no doubt, new advice on ways to navigate them. Or, on the other hand, investors can throw in the towel and merely match the market, less fees, with an index fund.

Windsor was never fancy, fad-driven, or resigned to market performance. We followed one durable investment style whether the market was up, down, or indifferent. These were its principal elements:

• Low price-earnings (p/e) ratio.

• Fundamental growth in excess of 7 percent.

• Yield protection (and enhancement, in most cases).

• Superior relationship of total return to p/e paid.

• No cyclical exposure without compensating p/e multiple.

• Solid companies in growing fields.

• Strong fundamental case.

In a business with no guarantees, we banked on investments that consistently gave Windsor the better part of the odds. It wasn’t always a smooth ride; at times, we took our lumps. But, over the long haul, Windsor finished well ahead of the pack.

Without a team of professional securities analysts to comb bargain basements, emphasize your inherent strengths. They usually reside in a heightened measure of awareness about a company or an industry that you know firsthand.

Individual investors often have special insights into the companies and industries that employ them. I don’t mean illicit inside information; I mean general knowledge about the best and worst companies in the industry, and why they line up that way.

Besides the quantitative aspects of industry fundamentals, you might have some notions about the qualitative aspects, such as prominent differences between company cultures and strategies. Some differences get exaggerated during their evaluation because people give undue and exaggerated weight to their own expertise, but at least you can put your life experience to work to improve your investment odds. Be wary, however, of investing exclusively in the company that writes your paycheck. You may like your employer’s prospects, but if business goes awry, you don’t want to see your nest egg vanish along with your salary.

Fairness to shareholders meant low transaction and investment management fees, coupled with incentives for exceptional performance and penalties for dismal performance. We met these hurdles at Windsor. Un- like funds that receive fixed annual percentages of assets under management, performance governed Windsor’s compensation. Similar incentives and penalties are scarce because most managers lack confidence in their ability to do well.

Lighter investment expenses are like a lighter jockey in a horse race. After the late Seventies, Windsor never assessed an up-front load. All of the proceeds we received from investors, we invested on their behalf. As for annual fees, whatever a fund charges it has to earn back, over and above its market performance, to stay even with the market.

From the book JOHN NEFF ON INVESTING with S. L. Mintz JOHN WILEY & SONS, INC. 1999