The English Renaissance, literature, thoughts, ideas, innovations and authors of this great golden age with references to the different European movements.

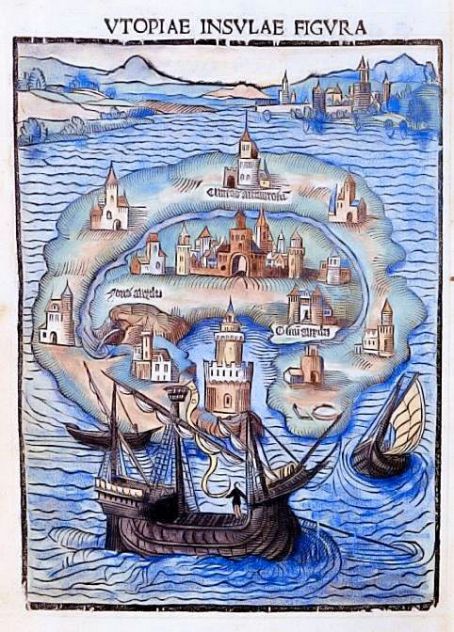

How can anyone be silly enough to think himself better than other people, because his clothes are made of finer woolen thread than theirs. After all, those fine clothes were once worn by a sheep, and they never turned it into anything better than a sheep.

Thomas More

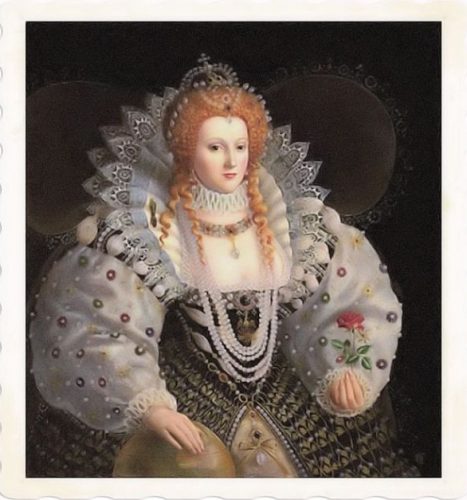

I have already joined myself in marriage to a husband, namely the kingdom of England.

Queen Elizabeth The First

While I thought that I was learning how to live, I have been learning how to die.

Leonardo Da Vinci

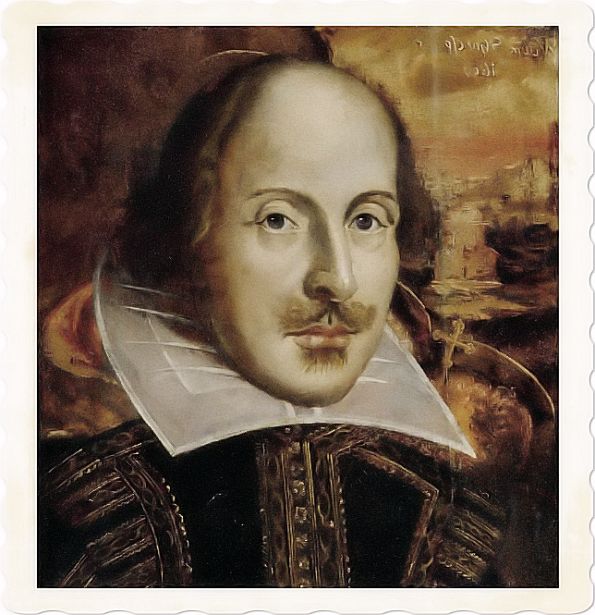

All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players. They have their exits and their entrances; And one man in his time plays many parts.

William Shakespeare

There is no greater hell than to be a prisoner of fear.

Ben Jonson

I was promised on a time – to have reason for my rhyme; From that time unto this season, I received nor rhyme nor reason.

Edmund Spenser

I was born in hell – and look to it, for some of you shall be my father.

Christopher Marlowe

We neede not speak so much of love, al books are ful of love, with so many authours, that it were labour lost to speake of Love.

John Florio

I beg you, reject antiquity, tradition, faith, and authority! Let us begin anew by doubting everything we assume has been proven!

Giordano Bruno

I have seen the shadow of the Earth on the moon, and I have more faith in the shadow than in the church.

Ferdinand Magellan

The light of past discovery draws me forward. Its shining light guides me to the glory of exploration.

Francis Drake

Truth does not change because it is, or is not, believed by a majority of the people.

Giordano Bruno

I have never met a man so ignorant that I couldn’t learn something from him.

Galileo Galilei

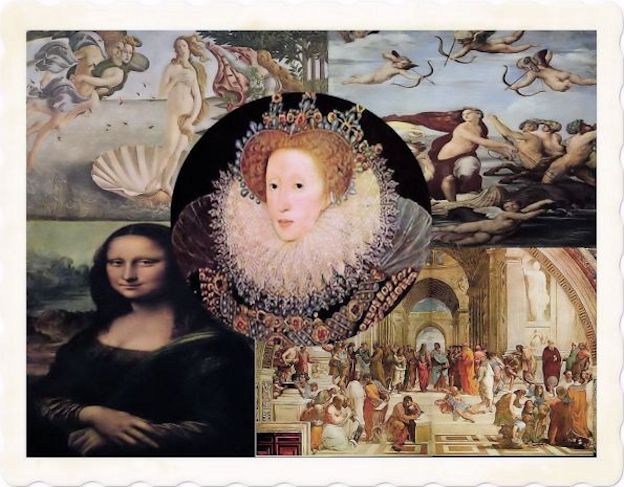

By the word Renaissance we mean that movement of thought which involved all fields, spread in many European countries and founded a new civilization, forerunner of the present one. The main idea of this movement lies in a strong and fresh belief in human creative possibilities; so that men can face all problems under, a new light. The word itself means “re-birth” and can be misunderstood. Someone might think of a re-birth of spirit from a dark age like the Middle Ages or of a re-birth of the classical spirit of ancient civilizations. Both concepts are wrong. First of all, the Middle Ages proved to be a many-sided period of great intellectual movements and deep feelings.

During that period there were a lot of ideas spreading in the field of culture, often contrasting between them, but they were all the expression of an extremely lively spirit. The Renaissance reacted against some of the ideas of the Middle Ages, such as the rigid submission to authority and dogma and the abstract moralism, but kept and improved many of the ideas coming from the great thinkers. It is enough to remember that Petrarca and Chaucer, who chronologically belong to the end of the Middle Ages, are considered the first Renaissance writers. As far as the classical spirit is concerned, there was not a return to the pagan past, a re-birth of classical ideas as they were, but a new way of reading and interpreting them, a direct contact between the reader and the classical author, similar to the need of the Protestant to read the Holy Scriptures directly.

By the word Renaissance we may consequently mean a deeper and fresher way to face ideas and to develop the human spirit copying with man’s problems. Men and the world are no more seen as mere spectators of God’s will, who perpetually assist to the fight of Good and Evil, of Grace and Sin, but as the protagonists of a marvellous creation in which God is costantly present as a Creator and not as a Persecutor. In trying now to find out the characteristics common to the Renaissance movement in different countries, it is necessary to bear in mind this vision of man who, under different points of view, is seen as the centre of his own life.

Chronologically speaking the Renaissance is usually placed in the XV and XVI centuries. It does not mean that these dates are to be kept precisely as the beginning and the end of such ideas. The feeling of human dignity and creativity had been already present in the Middle Ages, especially at the end of it, when the religious crisis had broken out. In the same way, the Renaissance may be seen as the beginning of a process of evolution of man’s thought which affected all fields and which formed the roots of our modern conception of life. Two centuries are involved because the movement developed differently in Europe, starting in Italy at the end of the XIV century with Petrarca and flourishing in other countries, such as England, only in the XVI century.

To outline the characteristics of the Renaissance in Europe, it is necessary to start from the concept of Humanism. This term is usually applied to the Italian Renaissance of the XV century, but, broadly speaking, it involves the main concept on which this movement is founded: a vision of the Universe based on man and his creative power and no more on God and His dogmatic doctrine. Human life becomes the centre of investigation of any real Renaissance man. Strictly related to the idea of Humanism is the second great concept of the Renaissance: the classical world taken as a human and cultural model by any scholar. The classical civilization is considered as the highest expression of man’s potentialities and the modern Renaissance man deeply desires to reinterpret it through the direct reading of ancient texts.

The fields which were affected by the new ideas were, more or less, all the ones in which human intellect is involved, but also those in which the spirit of adventure is necessary. Before facing the great literary and scholarly fields, we remember two aspects of the period in relation to the new concept of man: the interest in travels and the flourishing of science. Travels in those times meant adventure and the possibility for men to prove their own courage and boldness. Beyond the economic aspect, there laid a series of deep incentives which were pushed by the new self-reliance in man’s potentialities.

The field of science was one in which a similar boldness was necessary, because science lacked the systematic instruments of the modern one and put itself in contrast with the religious dogma which had governed it all over the Middle Ages. Scientists were pushed by the need to rediscover the great classical authors and to practically help man in everyday life. One science which much developed for practical purposes was astronomy, because it was necessary for navigational needs. The notion of the Earth as a planet revolving round the sun was put forward by Copernicus who interpreted the ideas of the Greek Aristarchus. Copernicus was much persecuted for his ideas by the Church, who openly declared her intentions to contrast the scientific development.

Another important expression of science in favour of mankind is the invention of the press, by which works of art and any kind of writing could finally be kept and used to be handed down to future generations as instruments of learning. A direct result of this invention was the spreading of Universities, places where the new culture could develop and the ancient world could be studied on original Manuscripts. The great field of culture has been divided into literary and scholarly because the Renaissance ideas involved not only the artists in the strict sense of the word, but any man of thought of the time. To the scholarly field belong those men who recovered and reconstructed the ancient texts by a fine philological work, those who studied the stylistic aspects of the same texts to rediscover their rhetoric and metre, those who were involved in literary criticism and set the roots of this science, but most of all those who were concerned with the interpretation of the ethical ideal of classical men.

In the literary field, the idea of man as the centre of the Universe was interpreted in very different ways by the many authors of the time, from the deepest ones to the pleasure-seeking ideas of “carpe diem”. It is much difficult to find out an author who embodies all these aspects; the common basic idea was the one of the classical man, from which each author developed his own ideas according to his own personality. Italy, France and England were the three European countries in which the Renaissance developed. Spain had too recently developed into the two reigns of Spain and Portugal and was still linked to the chivalric ideals of the Middle Ages. Germany and the East of Europe were still under the grip of a strict medieval system which deeply hindered freedom. In Italy the field of scholarship was much fertile in many sectors, like philology, historiography, treatise, science, etc.

In the literary field, the vision of man is linked to the idea of “Carpe diem.”, of seizing everything that life offers in the right moment and to deeply live it as a unique moment. In France, the two great authors of the Period, Ronsard and Rabelais offered different visions of life: a life which is short and so it is necessary to be seized when one is young, for Ronsard, and a life seen in its satiric aspects, for Rabelais. In England the literary field was all the same much varied: from the lyrical optimistic view of man of Spenser and Sidney to the the deep interpretation of human nature made by Shakespeare. It is however, in the field of ethics that the complete Renaissance man could develop; as a matter of fact, essayists were the men who gathered the many aspects of this new culture in their works. The three main thinkers of this kind are the French Montaigne, the Dutch Erasmus and the English Thomas More. They all believed in the great ideals of classicism; but they were also opened to the ideas of their time and to reinterpret the medieval concepts of religion and man. They all had a humanist attitude towards life in the broadest sense of the term.

The Renaissance in England

Chronologically speaking, the Renaissance in England spread in the XVI century, more precisely it started under Henry VIII’s reign and reached its peak in the Elizabethan times. Like in Europe, however, the movement was not born in a night and many of its ideas can be found out at the end (of the Middle Ages. Chaucer himself could be considered a Renaissance man for his belief in human possibilities and his interest in the many aspects of human life. Let’s say, then, that the XVI century saw the climax of a long evolution of ideas ‘thanks to a much favourable political and social situation. As a matter of fact, the movement in England was not confined to the world of thinkers and artists, to the elevated environment of courts and manors, but it involved the whole country, the growing wealthy population of England.

The relationship between the social, political world and the field of ideas is a characteristic of English history. Today, culture is intended as a right to be given to everybody; the intellectual world is strictly related to all the events of our society and no one could think of literature as separated from the problems of a man living in this society connected to other societies. This concept of involvement of all the aspects of human life in the literary field and of every man, disregarding his social status, is quite recent and has developed after the revolution caused by industrialization. In the XVI century, like before and after, culture was a concept related to those who needed not work in their lives and so to noblemen or people connected to court life. Many of the movements of ideas that are studied today belonged to a restricted and privileged minority of people, the majority being involved in surviving problems and being usually given few or no rights.

This was not the case in England. Following the teaching of the Norman kings, the concept of the national state included all the subjects of the Crown able to foster and to promote the wealth of the Nation, disregarding their social status and their cultural level. During the Renaissance period, the Crown favoured the process of evolution of its subjects as never before. The ideal Englishman was not only the typical Renaissance scholar, but also the bold merchant who worked for himself and for the nation notwithstanding the many dangers of the time. It is for him that the Tudor kings and queens worked out their domestic and international policies: they reformed the Church in order to create a new religion more suitable to the practical mentality of the mercantile class; they fostered scientific discoveries such as the press, which made it possible to enlarge the spreading of culture and of ideas; new astronomy, which was so important for the new navigational needs; new geography, which helped adventurers to discover new worlds and new markets; they favoured all those political actions intended to stir up the national feeling and the belief in the greatness of England as a nation.

The Court became the centre of culture and ideas, but it didn’t close its gates in the name of noble superiority. On the contrary, it was a centre shedding light over the nation through the creation of several branches in different sectors. There followed, therefore, the creation of Universities as centres lay culture, the birth of the Press industry intended to spread the thought of great thinkers and scholars beyond the works of many artists, the building of theatres as meeting places for people of any social position to discover the beauty of such catching form of art.

Such an organization of the State and of its subjects was the interpretation England and her Crown gave to the Renaissance ideals of culture and thought. Individuals became more aware of their potential skills and exploited them under a national light. This golden period of English policy, literature, science, philosophy and social situation is the result of the merging of domestic traditional ideals over men and the nation and the new European ideal of the Renaissance man.

By the time Elizabeth ascended the throne, the humanist movement had spread its ideas in the English scholarship, to the benefit of several different fields of thought. All over the first half of the century the Renaissance ideas had made them felt in England and had progressed constantly, despite the barbarian murder of the great Humanist Sir Thomas More, which had arrested the movement for a generation. The development of Humanist ideas favoured a direct contact with classical culture and many sciences could begin where Greek ones had stopped.

Translations from Greek fragments of ancient scientists allowed new discoveries in medicine, astronomy, physics, geography, fostering economic development and self-reliance for the mercantile class, gentry and working nobility. This advantageous situation in the fields of social and political stability was much bettered by the Queen’s cult for the nation, pride for the English economic supremacy and confidence in everyone could help England become great, even the humblest. She really believed in her people and never forgot to help them in any field, including the cultural one. The background was thus extremely favourable to let a great literature develop.

Two are the literary genres which knew a golden period during the Elizabethan age: poetry and especially theatrical production. As far as poetry is concerned, the output of poets during Queen Elizabeth’s reign was the result of quite a century of improvements and experiments. A change from the medieval production was necessary because the new optimistic ideals of the Renaissance poets needed a more adequate form of expression. Moreover, language had changed a lot after Chaucer and poetical patterns had been destroyed by over a century of darkness in the field of letters. The model was once again taken from Humanist Italy, from a very conventional verse form which had shaped the genius of several great poets, the most important being Petrarca. The poetical form was the sonnet.

The sonnet is a metrical pattern which obliges the poet to use discipline and skill to insert his ideas in its fourteen lines extremely balanced in links, pauses and rhymes. The balance and the system of rhymes can change provided that the fourteen lines are kept. The result is a musical and fresh piece of art much more suitable to the changes that had occurred in the language and to the new ideals of that time. Love became a favourite theme for the poets, following the example of Petrarca and Laura. From the beginning of Henry VIII’s reign to Queen Elizabeth accession to the throne, poets experimented and prepared the way to the great poetry of the golden period. Most of these attempts were clumsy and grave, but some of them were successful and proved to be models for greater poets. In the period of Elizabeth, time had come to give birth to a poetic genius embodied by Edmund Spenser.

Many students could think that Shakespeare living in this age, no one else could better represent the artistic protagonist of the time, both as a playwright and as a sonnetist. Speaking about the genius of a specific period, we mean that artist who better interpreted the events, the ideologies, the feelings of his epoch and was able to give the reader a faithful picture of the outer and inner mood of the time. Shakespeare was not an artist of this kind.

Although not at all unaware of the problems and feelings of Elizabethan England, his works deal with superior themes, universally acceptable and specifically suitable to any period. He detected human mind and deeply analyzed passions and foibles of the men of yesterday like the men of today. That’s why when dealing with the poet or the playwright who best represented Renaissance England we do not speak of Shakespeare. As a poet, Spenser was really the one who synthesized all the attempts in the formal expression and all the ideals which had so much altered the literary contents: he was really the interpreter of both Elizabethan ideals and European Renaissance culture merging them into a many-sided production.

As a matter of fact, both formally and as far as contents are concerned, Spenser’s poetry ranges from different styles of many epochs to praise for the best ideals of both national enthusiasm and European Humanism. His first work The Shepherd’s Calendar is a clear example. The form is the one of the eclogue, or pastoral dialogue, a very ancient form coming from Theocritus and used all over centuries by many different schools and poets, such as the great Virgil. Although it was considered not so important like epic poetry or tragedy, it was used in Renaissance Europe and was lighter than the other two genres. By using, it, Spenser was able to show a variety of poetic styles – lyrics, satire, elegy, allegory – and to deal with several subjects – love, religion, art, power, court. From this first work to his last one, his masterpiece The Faerie Queene, many years passed, but the same style remained, although it was improved by experience.

This long epic-allegorical poem borrows the style of the Italian poem by Ariosto and draws a picture of everyday England from a religious, political and social point of view filtered through the light of classical ethics and philosophy, humanist idealism, Protestant patriotism, English folklore, Elizabethan policy and conventions, European thought. To fulfill such an ambitious plan, Spenser collected formal tradition of any epoch, from classical poetry, to Renaissance Italian literature to English medieval works and merged them together in a new fresh epic poetry, really renewed, which would influence English literature for many years. The Faerie Queene may, at a first sight, appear as a series of pictorial, descriptive scenes, detached one from the other, but, although it is unfinished, it finds its coherence in the flexible use of allegory which shifts the tone of the work from realistic moments to extremely spiritual ones, gives characters different strength and results in an apology of Elizabeth – the Faerie Queene – her reign and Classical Renaissance ideals.

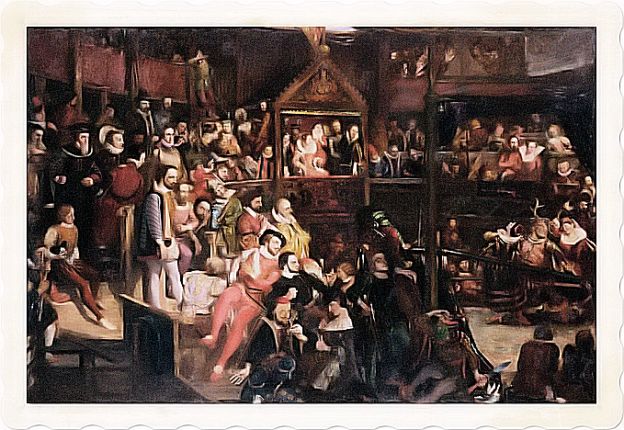

Drama is, with no doubt, the artistic form by which Renaissance English literature best expressed its ideals and forms. This was made possible not only by the ingenious personality of William Shakespeare, but also by the characteristics of drama itself, its direct contact with people, its religious tradition, its involvement in popular production, its realistic language. These features made this form art suitable to interpret the ideals of Queen Elizabeth who aimed at glorifying the greatness of the English nation by recovering its artistic-linguistic tradition and by involving all the people.

Medieval drama was the direct source from which XVI century authors drew inspiration. It had evolved all over the XV century, even when other forms of art had practically disappeared owing to the difficult political situation. Miracle and Mystery plays grew side by side with Morality plays all of them sharing, for a long period of time, the characteristic of being based on religious subjects. During the XV century there developed a kind of Morality play in which themes were dealt with in a more realistic and comic way. This is known as the Interlude. Although not completely new – remember the French fabliaux – the Interlude marks the passage from medieval moral-religious themes to XVI century drama. From the still extant Interludes of the period of transition between the two centuries, a shift is extremely marked from salvation-religious themes to education-political themes, so cherished by Renaissance scholars.

It is not that biblical plays disappeared, they only progressed together with these new works in which the Renaissance ideals became much important. Moreover, the specific English situation – the building of the Nation, the religious Reformation, the greatness of the Tudor dinasty – particularly fostered the development of this trend in Morality plays. When the Humanist culture deeply broke into the English literary context, classical tradition became much important and caused the birth of the English tragedy. Neither Miracle, nor Mystery, nor Morality plays had never been written in the form of tragedy. It was the interest in classical Italy and Greece that made the English tragedy be born. All the first half of the XVI century was of course a period of experimentation, of evolution and of attempts. By the time of Elizabeth, however, time had come for the birth of great playwrights, who gave England possibly its best period as far as theatrical production is concerned.

Before dealing with the two great playwrights of the time – Marlowe and Shakespeare – is important to have a look at the evolution of theatres as meeting points for people of different social status. One of the most important characteristics of dramatic production is that it is written in the aim of being performed, i.e. of being represented to a public, whose involvement in the development is fundamental. Because of this feature, drama proved to be a much suitable form of art for a XVI century England whose queen was trying to involve all people in the building of a strong economic power. The aim of Queen Elizabeth was to create a fierce class of people whose work would be taken as the foundations of the nation.

These people – well represented by the mercantile class – needed not only the possibility to trade freely; but also cohesion – and the Church of England aimed at giving it to them – as well as culture. That’s why the creation of lay Universities and the spreading of books were so important. Drama seemed the form of art most readily understandable by this group of people who did not, of course, read Latin and were not acquainted with the great thinkers of the time. Through drama, they could face the great ideals of their nation and of man in general, know something about their history, think about the meaning of life and amuse themselves altogether.

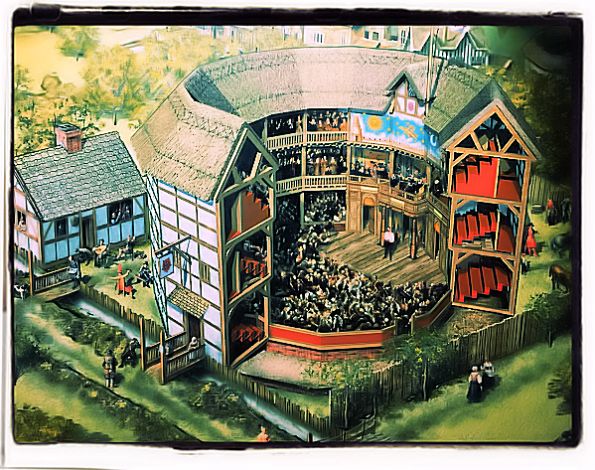

Such a form of art, bearing on its shoulder the burden of educating a whole generation, needed of course adequate places for its performances and professional authors and actors. Ancient churchyards and clerical actors were no more convenient for the works. No one, thus, hindered the creation, little by little, of specific places – theatres – where to perform and of guilds of actors specialized in the art of performing. No one, of course, could prevent great authors from standing out among the many who experimented with this art. First of all, performances shifted from churchyards to inn-yards. They were usually round-shaped, with one or two floors around the stage which was divided, into front, back and upper stage, consisting in a part of the existing balcony and necessary for many scenes.

In 1576, James Burbage, an actor, decided to erect the first building aimed at dramatic performances only. He was allowed to build it in the outskirts of London and called it The Theatre. Burbage took inspiration from the shape of the inn-yards, so that all the following theatres of the time kept a similar shape sometimes hexagonal or octagonal outside, circular inside with an unroofed centre in the middle of which there was a platform used as a stage. Very few theatrical devices were used and the background or scene was much due to the imagination of the public. The Curtain, the Globe, the Rose, the Swan, etc. were all built before the end of the century. Together with theatres, many companies were formed under the protection of powerful noblemen. They were authorized to act in the lands of their lord and were made up of professional actors, men only, women being not allowed to become actresses. There existed also a court theatre whose performances were meant only to be acted at court.

However the separation between court and popular theatre was not strict and this meant an exchange of ideas between the highest and the lowest ranks of art. In such a context many were the young people who undertook to write plays; not all of them succeeded in becoming famous, some of them are considered enough good, such as the University Wits, and contributing to the fulfillment of the golden age of the English theatre. Two of them are considered geniuses: Cristopher Marlowe (1564-1593) and William Shakespeare (1564-1610). Marlowe’s genius is much similar to Shakespeare’s one, his only fault being his very early death at only 29, when he was still experimenting. He is considered the first, among the many playwrights of the time, who was able to free blank verse from rigid methods and to give strength to theatrical poetry. Eloquency and musicality are the two characteristics of Marlowe’s poetry, which results in a very powerful and at the same time melodious verse.

This “mighty line” perfectly supports Marlowe’s characters in whom the author synthesizes the Humanist ideal of a man invincible and self-reliant, able of conquering whatever he wants if he engages his heart and mind to the greatest enthusiasm and several universal passions, common to the men of every time, by which they are usually taken to destruction. His hero is the classical man, together with the humanist scholar, the Elizabethan politician and any man of any epoch who has felt, even once in his life, the power of his reason and of his emotions. Two are the most known characters of Marlowe’s production belonging to his two best works: Tamburlane or Tamburlane the Great and Faustus or the Tragical History of Dr Faustus. Both these men ignore any moral concept and show boundless ambition in the fulfillment of their ideals.

For Tamburlane it is a matter of political power, the achievement of which allows Tamburlane to act outside any ethics in the name of an impressive self-confidence. Faustus ideal is more intellectual, but not less strong; he aims at power in the knowledge field. His empire is intellectual and his behaviour is thus less boasting, but similarly determined. Such a confidence in their own possibilities, such a challenge to moral rules, such a strong belief in reason and man’s faculties will weave the threads of a magnificent tragical ending, where both men are destroyed by their own greedy passions. No one can say how Marlowe’s genius would have evolved, had the author lived longer. What is nowadays recognized is that he was really the only one who could be ranked on the same line with Shakespeare and who first took English dramatic verse to the best possible effect.

From a text by Monica Beretta

About this period you can also read:

William Shakespeare aphoristic dictionary (part 1)

William Shakespeare aphoristic dictionary (part 2)

William Shakespeare and John Florio!

John Florio quotes, proverbs and aphorisms

William Shakespeare’ s literary reputation!

The greatness of William Shakespeare

Thoughts and literary quotes on Shakespeare

Aforismi geniali di William Shakespeare by C.W. Brown