The Victorian society, a complete article that explains the atmosphere, the main characteristics, and the most important social events of this glorious period.

Great events make me quiet and calm; it is only trifles that irritate my nerves.

Queen Victoria

The important thing is not what they think of me, but what I think of them.

Queen Victoria

We are not interested in the possibilities of defeat. They do not exist.

Queen Victoria

The best way to become acquainted with a subject is to write about it.

Benjamin Disraeli

Give a man a fish and he will eat for a day; teach a man to fish and he will eat for a lifetime; give a man religion and he will die praying for a fish.

Benjamin Disraeli

Enlarged sympathy with children was one of the chief contributions made by the Victorian English to real civilization.

G.M. Trevelyan

Victoria (24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was from 20 June 1837 the Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and from 1 May 1876 the first Empress of India until her death. Her reign as Queen lasted 63 years and seven months, longer than that of any other British monarch to date. The period centered on her reign is known as the Victorian era. The Victorian era represented the height of the Industrial Revolution, a period of significant social, economic, and technological progress in the United Kingdom where the theories of Jeremy Bentham, Carl Mark and Charles Darwin were spreading about. Victoria’s reign was marked by a great expansion of the British Empire; during this period it reached its zenith, becoming the foremost global power of the time.

During the reign of Queen Victoria Britain emerged as the most powerful trading nation in the world, provoking a social and economic revolution whose effects are still being felt today. Since the latter part of the eighteenth century the process of industrialisation had built a firm foundation for nineteenth century growth and expansion. At the heart of this was the successful development and application of steam technology. Like the steamship, the railway predates the Victorian era. By 1845 2441 miles of railway were open and 30 million passengers were being carried. The building of the railway network was the major achievement of the Victorian period, changing for ever both social patterns and the landscape of Britain. Other useful inventions of this period were the Telephone, the Radio, the Refrigerator, the Toilet, the Camera, the Sewing Machine, the Stamps and the Vacuum Cleaner. There were also significant improvements for food preservation and the first “canned food” like dried soups and chemicals appeared. (Pasteur’s theories).

When Queen Victoria, an inexperienced eighteen-year-old woman, came to the throne there was a certain amount of scepticism. Many were convinced that the monarchy would not last long. However, from the very moment in which she was crowned in Westminster Abbey in 1837 she did not appear afraid of the solemnity of the occasion and the hundreds of people looking at her. Initially she was greatly helped by her Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne (1837-1841). In 1840 she married her cousin, Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. Victoria was thoroughly devoted to Albert, she gave him the title of Prince Consort and did nothing without his approval; they lived in close harmony for 20 years and had a family of nine children. Albert’s early death of typhoid fever in 1861 came as a shock. Victoria was devastated; she found herself alone in her public duties. For forty years she reigned as a widow, wearing black till the end of her life at 82 years of age. She was succeeded by her eldest son Edward VIII.

She soon won the nation’s hearts with her modesty and practicality. She personified perfectly 19th century middle-class femininity and domesticity centred on the family, motherhood and respectability, she did not identify with the aristocrats and the intellectual but she was very near to the common man in the street. Her reign, the longest in the history of England, coincided with a period of unprecedented material progress, of imperial expansion, and also one of interesting political an constitutions during which the relations of the Crown to Parliament and of Parliament to the nation were more clearly defined. England emerged from the Victorian era with a consolidated democracy and an efficient system of government. The merit of all this belongs partly to the queen who, in marked contrast with continental. monarchs, from the first showed her intention of ruling constitutionally.

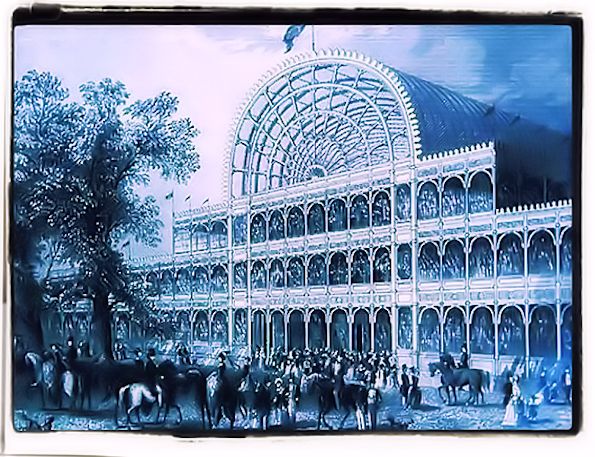

The years from 1848 to 1870 therefore marked a period of prosperity and relative tranquillity: trade and industry flourished, while a succession of Parliamentary Acts (Factory Acts) limiting working hours and restricting child labour, improved the conditions of the lower classes, and in 1870 Parliament passed the Education Act which made elementary education compulsory. One of the main aspects of the age was the growth of heavy industry and transport. The defining technology of the age was the railway. Locomotives and other industrial Machinery required improvements in iron and steel production; advances in British steel technology soon made it possible to construct iron bridges, while ships were increasingly built of steel and powered by coal and steam. The highest point of Victorian prosperity was marked by the inauguration in 1851 of the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park. The Exhibition was housed in the Crystal Palace, a glass and iron structure erected according to the most advanced techniques; it became the symbol of progress and of the British spirit of enterprise.

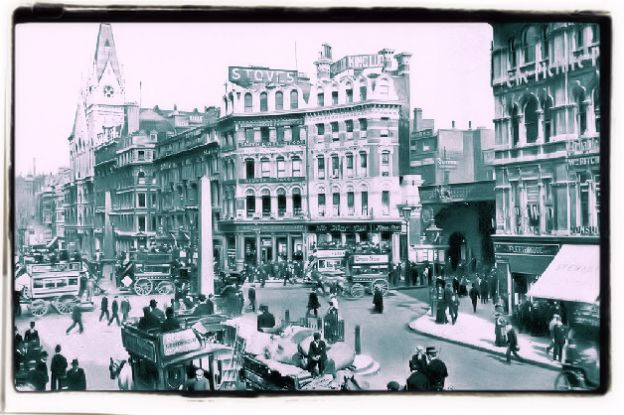

London had become the world centre of finance and shipping, moreover, the railway had greatly influenced trade and social life, as communication and transport from one part of England to another was greatly sped up. Life had become a little bit easier thanks to the improvement of little things of life; gas and oil were substituted by electricity, there was more clothing, food and furniture. Despite these improvements, life was still very hard particularly for the working classes, both in the town and the country, where low wages, long hours, miserable living conditions, poor sanitation and disease were common.

Because England was the first nation to industrialize, it experienced fully not only the positive but also the negative aspects of the process. During the reign of Queen Victoria, while Great Britain developed into the greatest political, industrial, commercial and financial power in the world, it also had to cope with a number of social problems which resulted from industrialisation. The early Victorians were aware of the social cost progress. They were conscious of the tensions and contradictions of their times, but they thought they would be only temporary and that sooner or later progress should bring an enormous increase in material wealth to all.

Utilitarianism, a social philosophy developed by Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832), was an important shaping force of Victorian culture. Bentham’s utilitarian philosophy was founded on two principles: firstly that terms like “conscience”, “morality”, “love”, “right” and “wrong”, were “vague generalities”; secondly that the worth of human life could be calculated to the extent that it succeded in avoiding pain and achieving pleasure, reminding us in this way the previous philosophy of Greek thinker Epicurus. He therefore stated utility lay in avoiding pain and securing pleasure, and that the duty of reason and the law was to create a system guaranteed to ensure “the greatest happiness of the greatest possible number”. In Bentham’s view, this would also become the criterion for judging government actions.

Much Victorian democratic legislation was inspired by the desire or need to secure the happiness of the greatest possible number by democratic reform and majority government. The Utilitarians believed that men could be rendered “happy” by having employment, being fed, housed; avoiding illness, receiving a factual education and avoiding physical pain. Such a view neglected the emotional distress, the spiritual aridity and the brutalizing ugliness of life in a world of useful facts, and it was ledt to the great writers of the day, such as Thomas Carlyle, Charles Dickens, J.S. Mill, John Ruskin and so on, to reveal the great psychological misery such “happiness” brought to many Victorian men and women.

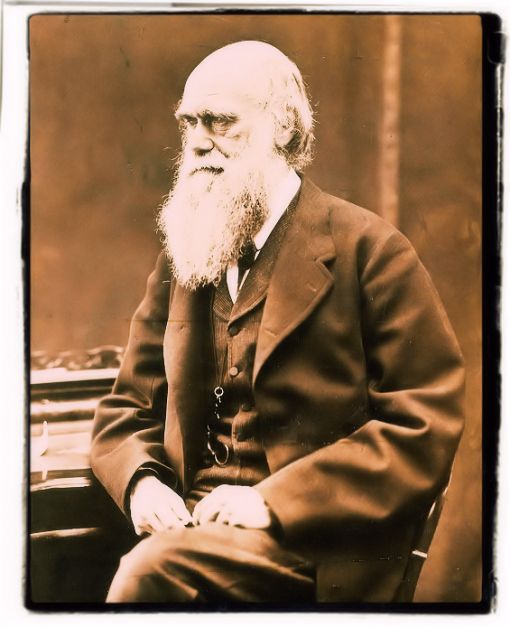

In Victorian Britain, pragmatism and morality had combined to create a wealthy nation and a climate of great national confidence. Yet, it was also a period of considerable social and moral uncertainty and intellectual ferment. The advances made in politics, science, industry and commerce were often so dramatic that people began to earnestly question both new developments and the old beliefs, as happened with the publication of Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, published in 1859, which challenged the very foundations of religion. The religious uncertainty that followed was for many painful and profound. The literal truth of parts of the Bible had already been challenged in the 1830s and 1840s by scientifically meticulous German scholars who had analysed it as a text of history rather than as a sacred text. In the same period new discoveries in geology and astronomy also cast doubts on the accuracy of the Book of Genesis. However, it was Darwin’s book on evolution that was the real cause of anxiety.

Darwin (1809-1882) was a British naturalist whose theory of evolution through natural selection caused a revolution in biological science and was deeply upsetting to many Victorians. Soon after graduating in 1831, Darwin sailed as a naturalist with a British expedition aboard the Beagle whose captain, Robert Fitzroy (1805-1865), published an accurate account of the expedition. During his five-year exploratory voyage along the coast of South America and to the Galapagos and other islands in the Pacific Ocean, Darwin searched for fossils, and studied plants, animals, and geology.

Back from his voyage, he settled in London in 1836 and began writing the first of his books On the Origin of Species. In this book he challenged the authority of the Book of Genesis, and his ideas about natural selection and the struggle for survival seemed to confirm men’s worst fears that nature was really a soulless and pitiless mechanism, however beautiful it might seem at times. By 1870, Darwin’s theory began to be accepted in the scientific world. But for others the controversy and the anxiety continued, stirred up even more by the publication of Darwin’s The Descent of Man (1871), which looked more directly at the question of man and the animal kingdom, and postulated the idea that man was only an evolved ape. T.H. Huxley, his great disciple, claimed for Darwin a place in science comparable with Galielo’s and Newton’s.

Religion in any case remained the strong foundation of the Victorian society and the basis for many Victorian attitudes lay in the religious movement known as Evangelicalism. This movement began in the late 18th century among members of the established Church of England who were inspired by the teachings of John Wesley (1703-1791), the founder of Methodism. Wesley emphasized individual religious experience and spiritual zeal, and the Evangelicals sought to bring his enthusiasm and sense of commitment into the established Church.

The Evangelicals were vigorously dedicated to humane causes and social reforms: their influence was instrumental in the passage of the First Reform Bill in 1832, and in 1833 they were responsible for the emancipation of all slaves in the British Empire. On the other hand, the Evangelicals believed in a strict, puritanical code of morality. As the century wore on, the Evangelical spirit permeated the material and commercial aspirations of the Victorian middle class, since hard work, individualism, sobriety, and avoidance of worldly pleasures led not only to spiritual worthiness but to success in business as well. In 1735 Charles and John Wesley set sail for America as missionaries, where John preached to numerous gatherings that also included Native Americans.

Perhaps the most famous embodiment of the Evangelical spirit was the independent member of Parliament and philanthropist William Wilberforce (1759-1833). After his conversion to this religious outlook, he headed the parliamentary campaign to abolish the slave trade, which was achieved in 1807 with the Slave Trade Act. Wilberforce was also committed to many initiatives to spread a Christian way of life both at home and by promoting missionary work in Britain’s colonies. Although he was accused of neglecting social injustices and political repression in his devotion to introducing morality into public life and society, it was largely thanks to his efforts that slavery was abolished throughout the British Empire with the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, which was passed just three days before his death.

What was the Church expected to do in the face of such serious scientific and philosophical challenges? One answer was to reinvigorate itself, not by emphasizing individual spiritual zeal, as the Evangelicals had done, nor by making its beliefs more liberal and flexible, but by returning to the ancient doctrines, rituals, and sacraments of the Church, when its authority was strongest. This kind of reform was advocated at Oxford University, where a group of intellectuals and clergymen, led by the brilliant John Henry Newman (1801-1890), who eventually became Cardinal, published a series of persuasively written pamphlets, “Tracts for the time”, thus beginning what was called the Oxford Movement. A number of Tractarians left the Church of England and joined the Roman Catholic Church.

The two English universities, Oxford and Cambridge, which had reached a deplorably low state in the 18th century gradually revived in the 19th century. In 1825 University College, which was open to members of all religions and non-believers, was founded in London. It was to provide an education for the bright offspring of the middle-class. The foundation of new universities in the largest cities continued through all the century. Public schools, private and fee-paying, were similarly transformed. Moral as well as intellectual training was to become an aim of the public school, whose popularity increased with the growth of a middle class which could afford the fees and an expansion of the railways which could transport boys from home to school. With the growth of the Empire in the late 19 century there was a need for large numbers of well schooled men who could take up posts in the army, the Civil Service and business.

The attitudes regarded as typically Victorian are primarily those of the middle-class: the new industrialists, merchants, professional men, and property owners who benefited directly from Victorian prosperity and progress. Middle-class Victorians believed in hard work, moral seriousness, and social respectability. They were progressive in that they favoured the new discoveries of science and the gradual attempts to make England a more democratic society. They were conservative and often repressive in their attitudes towards worldly pleasures, private emotions, and personal relationships.

While this moral outlook encouraged the spread of good behaviour and greatly increased the civility and the gentility of life, it also encouraged intellectual narrowness and a climate of conformity. These were years in which Shakespeare was read in Thomas Bowdler’s (1754-1825) expurgated versions. In this repressive atmosphere, the novelist William Thackeray (1811-1863) complained that it was no longer possible for a writer to depict a man in all his powers.

The somewhat conventional morality of the time found its best expression within the family. The centre of family life was the father, and male domination was carried farther than before. The only work a woman could do was to be a dutiful wife and fruitful mother. Middle class women in general were expected to adhere to a strict code of behaviour, which required them to be frail, innocent and pure, confined within the family walls or, at the most, devoted to a few respectable jobs like teaching or social activities. A woman who departed from the rule of single chastity or married fidelity was an outcast. A regular feature of Victorian family life was family praying and Bible reading, which took place daily and was often attended not only by the family but by the servants, whom, considering the size of Victorian families and houses, were numerous.

In the industrial areas, the factory system displaced the domestic system which had enabled women to work in their homes. Women often worked in the factories, but this interfered with the upbringing of young children. Nevertheless, working women began to achieve a degree of economic independence, though limited, which was often denied to women of higher social rank. Women of strong character began to start or join the ranks of the professions. They became writers and journalists, as the remarkable succession of women novelists in the century shows. For educated women, teaching became an expanding profession after the middle of the century. In April 1867, John Stuart Mill, in one of the debates of the Reform Bill, argued that it was time to give women equal rights at the ballot-box. Two years later, in May 1869, Elizabeth Stanton founded the radical National Woman’s Suffrage Association.

Victorian were certainly class-conscious, but the vast wealth produced by the Industrial Revolution enabled people of all classes to improve their social position. One of the most popular books of the 19th century was Samuel Smiles Self-Help, published in 1859, which claimed that success was the product of four virtues, thrift, character, self-help and duty. Dickens novels are filled with characters aspiring to better themselves. The colonies and America were an important outlet for people who wished to break with the constraints of home and chance their luck. Anyway Britain wealth increased a lot in the 19th century, and though its distribution was highly uneven, the increase in prosperity among the working class was sufficient to give its members a growing feeling of betterment and security.

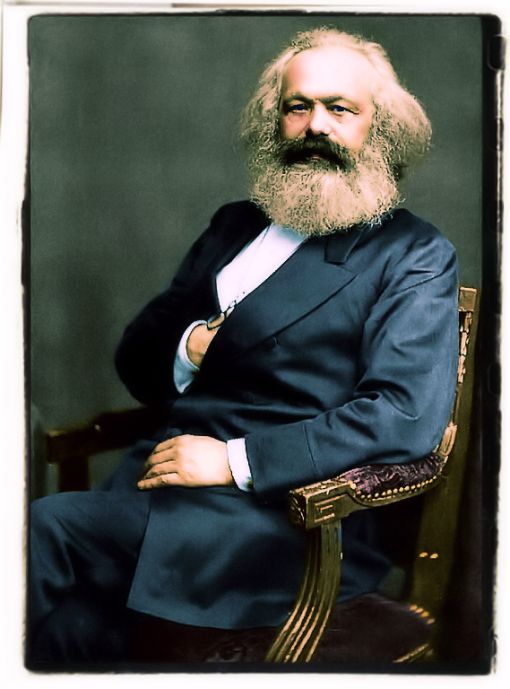

The Victorian Age saw the development of radical new ideas and political theory. Although the writings of Karl Marx (1818-1883) and his Das Kapital had little immediate influence on the minds of English workers, it is significant that his theories on a new social organization and on a new distribution of wealth were based on research done in England, in the Reading Room of the British Museum. The outstanding political phenomenon of the late 19th century was the new democratic electorate created by the Reform Acts of 1867 and 1884. The traditional political parties, the Liberals (formerly Whigs) and the Conservatives (formerly Tories) no longer seemed to satisfy the electorate. This political neglect and the anxiety caused by the economic depression of 1870s and 1880s led some people to search for more radical solutions.

The Fabian Society, organized in 1884, was one of several socialist groups formed about the same time. It was unique however in its respectability, disavowing violent revolutionary means and attracting to its membership notable intellectuals like the historian, Sidney Webb (1859-1947) and the playwright George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950). It took its name from the Roman general Quintus Fabius Maximus, who had beaten Hannibal by refusing a direct confrontation, confident that by being patient and prepared, the victory would ultimately be his. In 1900, the Fabians joined with other socialist groups and labour unions to form the Labour Representation Committee, which in1906 became the Labour Party.

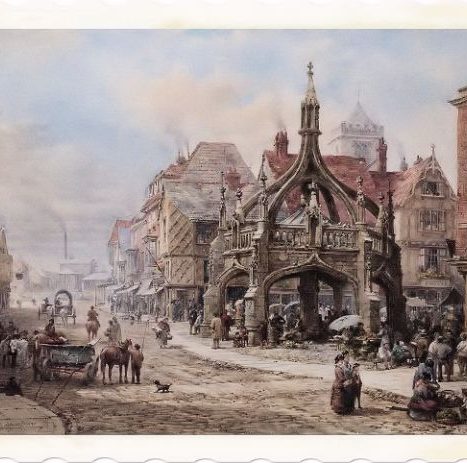

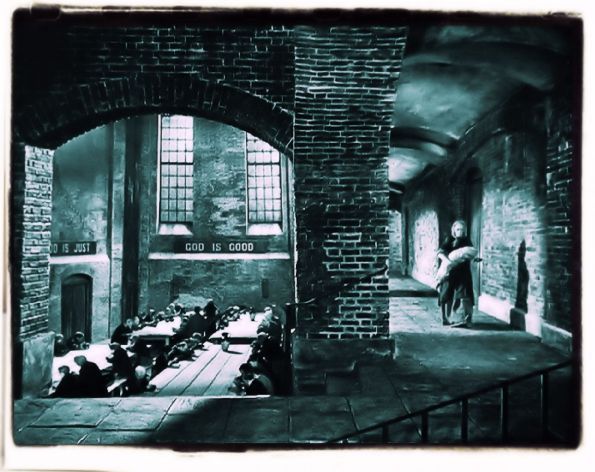

London in Dickens’ Time. During the 1840s London quickly became a very big city. In 1850 there were a quarter of a million more people than in 1840. In the area of St Giles 2,850 people lived in only 95 small houses – about 30 people in each house! In these poor areas, conditions were terrible. The streets were very dirty, and people drank and cooked with bad water from the River Thames. In 1847, 500,000 people died of typhus fever in one month. In winter the fog was often very thick; in summer the smelts were horrible.

In one of the most famous areas, Seven Dials, there was a street of second-hand clothes shops called Monmouth Street. Dickens describes it in Sketches by Boz, and Old Joe has his shop there in A Christmas Carol. The Seven Dials area was full of thieves and poor street-sellers. Many of the old buildings were cleared away when Charing Cross Road and Shaftesbury Avenue were built. Children aged only nine worked in factories for many hours a day. A lot of very poor people went to workhouses, where they worked very hard in bad conditions, or they lived in very squalid conditions in prison. In 1837, between 30,000 and 40,000 people were in prison for debt. Victorian London was very busy, crowded, and noisy. It was the capital of a country in the middle of a scientific and economic revolution, and which was creating a huge empire across the world.

What did a Victorian house look like? If the owner had a lot of money, the house was very comfortable. Houses in pleasant parts of cities were often built in terraces. They might have three floors and a large cellar. There were gardens at the front and back. On the ground floor was a dining room, where the family ate their meals. There was a drawing room, where people sat in the evening and played cards or listened to music. Victorian families liked to sing together. At the back of the house or in the basement was the kitchen and scullery, where the washing up was done. Big houses had breakfast rooms, studies and sometimes libraries. The bedrooms and nursery were on the first floor.

The servants lived in the attics at the top of the house. The dining room had a large central table surrounded by wooden straight-backed chairs. The father of the house sat at the top end of the table. He cut up the meat for the rest of the family at mealtimes. The drawing room or parlour had leather armchairs, a sofa, sideboards and maybe a grandfather clock. The rooms had open fireplaces. The beds were warmed at night with a stone bottle filled with hot water. Because few people had bathrooms, people washed in the bedrooms. There was a washstand in each bedroom with a large jug and basin. When the family had baths, a servant carried a small bath to the bedroom. She filled it with hot water which had to be brought up from the kitchen. Rich people usually had an indoor toilet, but in poorer people’s houses the toilet was outside. Cottages were very simple. Sometimes there was just one room downstairs, which was both a kitchen and living room, and a bedroom upstairs. The floor was made of stone, with no carpet in poorer homes. The water was brought from a pump or well outside.

The Christmas spirit and the general need for easier communication. Families and communities were breaking up as people moved from the countryside to the towns for work. In 1840, Rowland Hill invented the postage stamp. The first were called “Penny Blacks” because they were black and cost a penny. They made communication easy and cheap for a population that was on the move and that encouraged people to write to each other. About 1843 the first Christmas card was sent and that encouraged people to write to each other at Christmas. Business and government required something quicker, and this came in the shape of the telegraph (1837) which rapidly spread throughout the country.

At the same time Charles Dickens was certainly responsible for creating the traditional image and the spirit of Christmas in Britain in the Victorian period. He wanted to create this feeling of goodwill and the family circle. But it was strange that he was writing Christmas Carol at a time when Christmas was experiencing a revival. Queen Victoria had got married and Prince Albert brought over that “pretty German toy”, as Dickens calls it, the Christmas tree. In this period Tom Smith invented also the Christmas cracker, roundabout the same time so all this jollification was happening and people began to take more interest in Christmas than they had done; it had gone really into abeyance for a while and, with Dickens’ input with the Christmas Carol, it suddenly had a revival and became extremely popular.

Food and Meals in the Literature of the Victorian period.

During Victorian times the diet of most people began to improve: the invention of steam ship and of refrigeration meant that meat, fish and fruit could be imported! People could begin to eat shellfish, poultry, game, cheeses but also exotic fruit (peaches, pineapples, etc.). The cooks were especially prized for their dessert-making skills-puddings, cakes, etc.

Victorian Upper-classes, at home:

The Victorian period was an epoch of compromise: progress and poverty; corruption and moralism.

• The woman planned lunch and evening meals (the largest one)

• She had a cook that did the work for her.

• They ate 5-6 courses when they were alone; 12-13 when there were guests.

• “Supper” is the Victorian mid-night snack

Afternoon tea: to show off the lady’s finest silver, china and linen.

Example of menu

• Soup

• Roast Turkey with dressing or

• Roast Pork with potatoes or

• Chicken Fricassee served with rice

• Two vegetable side dishes

• Citrus ice

• Jam, jellies and sweet pickles

• Cake and preserved fruit

• Coffee, hot punch and water

Victorian middle class

• The Victorian middle-class family has become a synonym for a strict, repressive upbringing.

• For nearly the whole of the century, married women were simply regarded as part of their husband’s property.

• Discipline was severe, beatings common and incredibly harsh conditions prevailed in the boarding schools of the time.

• Parents were typically distant and unemotional, and the family home was a very closed environment, with little chance for women and children to have contact outside their immediate family circle.

• Sex and other “taboo” subjects were rigidly avoided.

Middle-classes at table

• During Victorian times the diet of most people began to improve: the invention of steam ship and of refrigeration meant that meat, fish and fruit could be imported!!!

• They can eat shellfish, poultry, game, cheeses but also exotic fruit (peaches, pineapples, etc.).

• Food preservation: the first “canned food” like dried soups and chemical to preserve food (Pasteur’s theories).

• The cooks were especially prized for their dessert-making skills-puddings, cakes,

Wine is served at the end of each course. Madeira and sherry after.

Breakfast with scones, fruits, omelettes, bacon and more.

• Complicated nutrition as a research for sensual experiences: the decadent character is spoiled by the finest china, silver cutlery and linen as well as by “elegant” food.

• All five senses were moved and stimulated.

• Food becomes a passion and intense experience.

• Food and meals as a way to remember the childhood or past and melancholic events.

To find out more about this period you can also read: