In defence of grammar, some quotes and a complete article by the famous language scholar Mario Pei who analyze the importance of grammar for learning a language.

The palest ink is better than the most retentive memory.

Chinese proverb

A world language is more important for mankind at the present moment than any conceivable advance in television or telephony.

Lewis Mumford

Language is as much an art and as sure a refuge as painting or music or literature.

Jane Ellen Harrison

The minimum grammar is no grammar at all.

Giuseppe Peano

Language exists only when it is listened to as well as spoken, The hearer is an indispensable partner.

John Dewey

Language is not an abstract construction of the learned, or of dictionary makers, but is something arising out of the world, needs, ties, joys, affections, tastes, of long generations of humanity, and has its bases broad and low, close to the ground.

Walt Whitman

Language is a city to the building of which every human being brought a stone.

Emerson

Language most shows a man; speak that I may see thee!

Ben Jonson

Grammar is the logic of speech, even as logic is the grammar of reason.

Trench

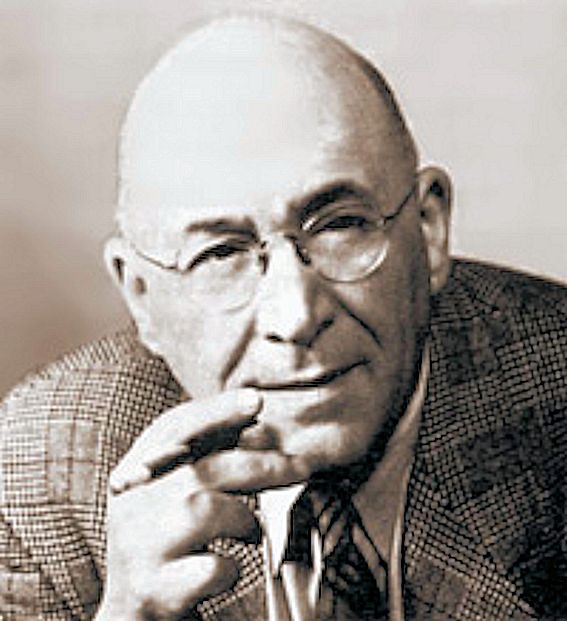

The Story of language is the story of human civilization. Nowhere is civilization so perfectly mirrored as in speech. If our knowledge of speech, or the speech itself, is not yet perfected, neither is civilization. Language is forever changing and evolving, as are all human things. Linguistics, the study of the laws governing the evolution of language, becomes socially significant only when it sheds light upon the people who speak languages and their civilization. When this light is properly cast, linguistics ceases to be the dry-as-dust subject that many people have suspected it of being, and becomes the most absorbing of pursuits – absorbing as the study of mankind itself.

Mario Pei

‘‘Grammar” is a term devised by the Greeks, in whose language it literally means “that which pertains to writing.” The modern tendency, however, is to regard grammar as the study o£ speech rather than of writing, or at least of both. The Romans had a saying Verba volant, scripta manent (“What is spoken flies away, what is written endures”), which perhaps serves to illustrate the point of view of the Greeks, as well as of grammarians generally. The written word, remaining as a permanent record, is worthy of greater consideration than the fleeting spoken word.

Mario Pei

During the early Middle Ages, brief glossaries for the use of travellers and missionaries were the vogue rather than full-fledged grammars. One such glossary, from the eighth century a.d., giving a list of Romance words and phrases for the use of German speakers, reminds one of a modern Army phrase-book; it contains such expressions as “Give me a haircut” and “Shave the back of my neck.”

Mario Pei

It is unfortunately fashionable in a few linguistic circles to regard literature as something set apart from language, to play up the spoken, popular tongue to the detriment of the written, literary language, and to view as “language” par excellence that form of speech which is most out of accord with the literary tradition – colloquialisms, vulgarisms and slang. That this attitude is a reaction against an earlier point of view which regarded literature and its language with undue veneration is beside the point. Language and literature are fundamentally one. Speech gives rise to writing, granted. But once writing has come into being, the written form begins to affect the spoken tongue, stabilize it, mold it, change it, give it a more esthetically pleasing form, endow it with a richer vocabulary.

Mario Pei

The well-known simplicity of English grammar, its lack of endings, the fact that English is already the most widespread language on earth, led them to suppose that with the proper reduction in vocabulary it would be easy for anyone to acquire their creation and use it as an international tongue, at least for purposes of unpretentious self-expression.

Mario Pei

In defence of grammar by Mario Pei

In the face of the onslaught of the linguistic scientists and its accompanying fanfare of publicity, traditional and progressive language teachers alike stood at first silent – some of them aghast. Then timid voices began to be raised, growing ever louder and more insistent.

“More time and smaller classes? That’s what we have been fighting for in vain for years! Give us eight hours a week and ten students to the class, and we’ll do better than the Army!” said some. “Conversational skill? Just what we have been cultivating in our students!” said others. “After all, how about all the people in America who can speak and understand foreign languages? They are our products!” “Native speakers? Aren’t we native speakers?” remarked the qualified many. “Don’t we cultivated Frenchmen, Spaniards, German? and Italians know and speak the languages better than barbers, bartenders and waiters?” “Recordings, soundscribers, foreign movies, radio programs?” said the rest. “Haven’t we been begging our administrations to put them in for the last twenty years? And haven’t we always been told that

we’d have to wait until the new gymnasium was built, or until the chemistry laboratory was fully equipped?”

Many pointed out that results at least as satisfactory, though not so spectacularly advertised, had been attained for years in institutions where the students were screened as to LQ., instead of being indiscriminately admitted just because they fell into a certain age-group. If educational administrations had been willing or able to pour into language teaching one-tenth the funds lavishly bestowed by the Federal Government on the Army Program, others insisted, there would have been no need for the Army Program. Still others pointed to the fact that the methodology of the Army Programs had been almost bodily lifted out of Berlitz, Linguaphone, Middlebury and the schools of anthropology.

However justified these counter-claims may be, they leave the root of the matter largely untouched. The question of priority in the discovery and application of a new method is on a par with an academic debate as to whether Ericsson or Columbus discovered America. From the practical standpoint, the important thing is that America was discovered. The point at issue, if any, is that the intensive Army Programs did more to shake language learning out of its traditional habits and complacency than any of the unpublicized evolutionary innovations that had silently crept in during the years between the two wars. More fundamental were the criticisms directed by a few thoughtful language scholars at the new methodology itself, as well as its applicability on a universal scale to academic language learning.

Taking the second point first, it was pointed out that a true duplication of Army Program conditions could never occur in peace-times, for lack of time, funds, teachers, equipment and pupil-interest. This objection is more easily disposed of than appears possible at first glance. Granted that one cannot expect Army Program standards to prevail universally in peace-times, there is no trouble about setting them up as an ideal goal. If a school cannot allow its pupils to devote thirty-six hours a week to language study, it can nevertheless raise the hours from three or five to six or eight.

If classes of ten are not possible, classes of twenty may be; they are surely an improvement over the old-style class of forty. If all the native-speaker and mechanical apparatus of the Army cannot be afforded, perhaps it will be possible to equip the institution with a few sets of recordings, and bring in an occasional foreign speaker. Far from being hindered in their attainment of these desirable objectives by the Army experience, progressive language teachers will be aided by its example, which can be cited to

administrators to prove what can be accomplished.

It is rather the desirability of the conversational objective per se that lends itself to discussion and debate, along with the educational psychology and linguistic philosophy that underlie it. During the war, we wanted people who could learn in a hurry to speak and understand the more common reaches of a foreign tongue for intensely practical purposes. Is that precisely what we want today? The reasons for undertaking language study in peace-times are many and varied. Some people want to learn a language in order to do what our soldiers did in war-times: go to a foreign country and get by with a minimum of intelligible oral exchange. But a good many others want languages purely as a cultural or research tool, to be able to read scientific books and periodicals, or works of literature, or commercial tracts.

For these people, is the conversational approach the best? Is it not in part a waste of time for them to labor to acquire a native accent? Will it avail them more to have a reading or a speaking knowledge of the foreign tongue? It is true that the one can be converted into the other, with a little time, patience and hard work, but which has a better chance to survive in the post-school years, when the former student is forced to turn his attention to other tasks; the spoken tongue which he has no occasion to speak or hear, or the written tongue, which he can cultivate in his spare time with a minimum investment in books?

It must not be forgotten that languages, like everything else, prompdy fall into oblivion if they are not constantly practised. People who wonder why they don’t remember the high school French they studied twenty years ago should quickly examine their consciences to find out how much high school algebra, chemistry, physics, or even American history and civics they can recall. Spoken languages are often forgotten by their own native speakers, if they are not practised.

How much chance, then, does a high school or college student have of retaining a conversational course, with its five thousand-word vocabulary and five hundred-sentence list, unless bad fortune sends him to Europe on a third world war while the knowledge is still fresh in his mind? Will not the intellective process of learning a language’s grammatical structure for reading and cultural purposes have a better chance of survival than the series of mechanical reflexes involved in the learning of colloquial phrases?

It is a fact well known to psychologists, though often ignored by spoken language advocates, that some people learn better through the ear, others through the eye. Some students are confused by the written form of the foreign language, but others find it impossible to reproduce sounds unless they have their written representation before their eyes. The eye can be the most powerful ally of the ear, as well as its enemy. The linguistic scientists, recognizing this fact, broke away from the Berlitz tradition to the extent of giving their students an English or a phonemic transcription of the sentences they taught them by ear through native speakers. The value of these transcriptions was doubtful. The English ones, equating foreign to English sounds, served to perpetuate English accents (KEY AIR OWE BAY BEAR for Spanish quiero beber gives you almost as bad a rendering as if you were to try to figure out the Spanish pronunciation for yourself.

The so-called “phonemic” transcriptions, on the other hand, proved in part too complicated for the students, and led to great confusion later on, when the actual foreign spelling had to be imparted. Students who had become accustomed to invuziverapa as the written representation of a series of French sounds found it difficult indeed to recognize these now familiar sounds when they saw them under the guise of the official French il ne vous y verra pas. All in all, the attempt to circumvent the hurdle of the discrepancy between spoken and written language in those tongues where the latter exists was anything but a brilliant success.

The deification of the native-speaker accent on the part of the new methodologists was almost as ludicrous as the earlier veneration of minor grammatical points and literary models by the traditionalists. It is a familiar fact that people can speak English quite acceptably even though they do so with a foreign accent. It is also well known that a strong slang or dialectal native accent can prove as unpleasant and partly incomprehensible as any immigrant dialect. Under the circumstances, the preoccupation of the linguistic scientists with nativespeaker perfection in the matter of sounds struck many as an exaggeration.

Their proneness to use substandard native speakers, often with a dialectal taint, was almost as widely criticized. It was felt by a good many men, not all of them traditionalists, that it would be better to have a class trained in speaking Italian by an American-born instructor who knew his correct Italian grammar and vocabulary than by an illiterate Sicilian who would be laughed at in any section of Italy but his own.

Another, more far-reaching point of criticism in connection with the mechanistic learning of phrases by direct imitation was the following: there is a “language” ear just as there is a “musical” ear. Some people are born imitators of sounds, others are not. The ones that are will profit immensely by conversational practice with native speakers, even to the point of being mistaken for natives. But there is nothing more humiliating than to be told you sound like a native when you speak, and then have to remain speechless because your knowledge of the tongue is limited to a few words and phrases learned parrot-fashion.

Language is only in part a matter of sounds; far more, it is a matter of grammatical structure and, above all, vocabulary. The acquisition of sounds is only the first step in the acquisition of a foreign language. Hence, excessive concentration on sounds, to the detriment of structure and vocabulary, is hardly desirable. Last, but far from least, is the objection advanced by some historical linguists and grammarians to the linguistic philosophy of the linguistic scientists, particularly their attacks on traditional grammatical terminology.

While the terminology of Greek and Latin is not applicable to all the languages in the world, it is applicable, with appropriate modifications, to the principal western modern tongues – French, Spanish, German, Italian, Russian, even English. Hence, the attempt to break down formal grammar and replace it with a new system based primarily upon spoken forms was deplored. There is hardly any point, for instance, to trying to sidestep the subjunctive by calling it the “unreal” form of the verb, or to relabelling masculine, feminine and neuter nouns as ”der, die and das-nouns,” or to using the name “form 3 of the noun” instead of “dative case” or “indirect object.”

There is even less point, in the familiar languages, to trying to peel a grammatical form out of a series of spoken sentences when the grammatical form is already perfectly known, or to indulging in any of the dozens of time-wasting processes developed by the linguistic scientists in the course of their investigations of obscure languages. The grammatical order prevailing in Greek and Latin, and passed on by those languages to those of the modern western world is to some extent symbolical of mental and even of social order. Most of the sloppy and confused thinking of today can be traced to the abandonment of the principles of order in the teaching of languages (particularly English) in the schools. The trained, logical minds of the past, which we occasionally admire and the absence of which we occasionally deplore, were firmly anchored to principles of order, in sociology as well as in language.

As a result of all these considerations, acceptance of the full methodology of the innovators has been rather slow. In the last chapter it was pointed out that many academic institutions have gone over to the conversational objective. In this chapter, it is well also to add that numerous schools and colleges, after going over to that objective, have reverted in part to their traditional methods, with only a semblance of innovation left in their courses. This is praiseworthy to the extent that it demonstrates a spirit of healthy caution and direct experimentation with new points of view.

It is deplorable insofar as it represents a reversion to smugness and indolence. The latter trend is exemplified by an experience in textbook publishing. A publisher, weary of French readers based on antiquated nineteenth-century short stories, decided to bring out a new type of book, containing twenty pieces, each written by a leading contemporary French writer. The book sold twenty thousand copies the year it came out, but only five hundred the following year.

The reason for its rejection after a preliminary trial was that it had proved itself “unsuited for our educational system.” This means that, in the minds of the people in charge, it is not the language-teaching system that must revise itself to keep pace with the foreign language, but the foreign language that must remain static in order to fit the antiquated educational system. The absurdity of this proposition is manifest, but fundamentally it is no more absurd than the system itself, whereby languages have been taught for years on the basis of outworn methods and models.

Can a balance be struck between the requirements of tradition, which demand that we hold on to what is worth retaining in our cultural heritage, and the demands of progress, which urge us to move on with the times and bring our language-learning ways up to date.? It is our belief that the two can be reconciled.

To find out more about this topic you can also read the following articles:

Mario Pei books on the language

Countable and uncountable nouns

The English language article ;

The world of English language ;

Short History of the Origin of English

History-of-the-English-Language.pdf

British-history-milestones-synthesis

Questions-about-the-english-language

History-of-English-Literature-Summaries.pdf

British_literature_history_chart_summary.htm

General_literature_history_chart_summary.htm

American_literature_history_chart_summary.htm

British_english_history_timeline.htm.

Videos:

History of English in 10 minutes ;

On Facebook ;