English accent variations, an article that analyzes what is accent, its origins and the different sociological and linguistic implications of this phonetic aspect of the language

There’s an accent shift, on average, every 25 miles in England.

David Crystal, Ben Crystal

German and Spanish are accessible to foreigners: English is not accessible even to Englishmen.

George Bernard Shaw, Pygmalion

Remember that you are a human being with a soul and the divine gift of articulate speech: that your native language is the language of Shakespeare and Milton and The Bible; and don’t sit there crooning like a bilious pigeon.

George Bernard Shaw, Pygmalion

The English have no respect for their language, and will not teach their children to speak it. They cannot spell it because they have nothing to spell it with but an old foreign alphabet of which only the consonants – and not all of them – have any agreed speech value. Consequently no man can teach himself what it should sound like from reading it; and it is impossible for an Englishman to open his mouth without making some other Englishman despise him.

George Bernard Shaw, Pygmalion

HOSTESS. Oh, nonsense! She speaks English perfectly.

NEPOMMUCK. Too perfectly. Can you shew me any English woman who speaks English as it should be spoken? Only foreigners who have been taught to speak it speak it well.

George Bernard Shaw, Pygmalion

I sold flowers. I didn’t sell myself. Now you’ve made a lady of me I’m not fit to sell anything else.

George Bernard Shaw, Pygmalion

I can’t turn your soul on. Leave me those feelings; and you can take away the voice and the face. They are not you.

George Bernard Shaw, Pygmalion

I shall always be a flower girl to Professor Higgins, because he always treats me as a flower girl, and always will; but I know I can be a lady to you, because you always treat me as a lady, and always will.

George Bernard Shaw, Pygmalion

The accent of one’s birthplace persists in the mind and heart as much as in speech.

La Rouchefoucauld

It almost boosts your self-esteem being screamed at by someone with an English accent.

Andrew Smith

The Glasgow accent was so strong you could have built a bridge with it and known it would outlast the civilization that spawned it.

Val McDermid

I think we are wise, we English speakers, to savor accents. They teach us things about our own tongue.

Anne Rice, Merrick

I learned several important things about myself: A. If a boy has an accent; I’d will fall in love with him. If he has an accent and glasses; I will want to marry him…

Felicia Day

I actually always try to not do a general American accent. I always try to give a region.

Janet Montgomery

English contains many variations of accent and even dialect, but unlike Italian or German, the dialects are rarely different enough to make comprehension impossible. True, a London Cockney would have a very difficult time in a conversation with a steel worker in Glasgow, and a Carolina cotton picker might find it difficult to understand and be understood by a sheep farmer from Australia, but a businessman from, say, Indianapolis, Indiana, U.S.A. would have few problems dealing with a businessman from Dublin, Ireland or Sydney, Australia, Auckland, New Zealand, Liverpool in England, Johannesburg, South Africa or Kingston, Jamaica. A reasonably educated standard English allows comprehension and communication all over the English speaking world.

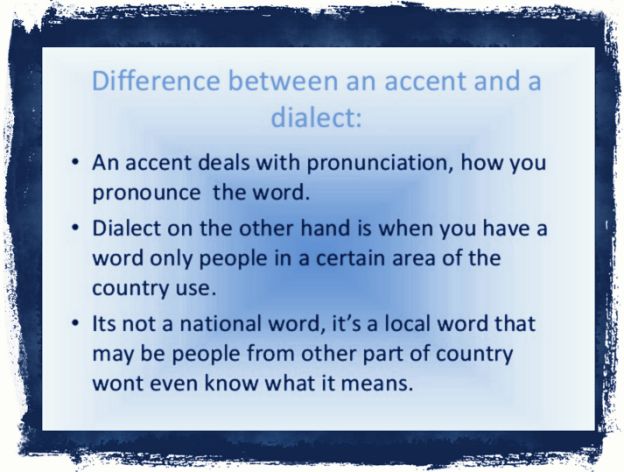

In any case you can usually tell after just a few words whether someone has a Scottish, Australian or American accent; you don’t have to wait for them to say some particularly revealing local word or to use some special construction. The important thing about an accent is that it is something you hear: the accent you speak with concerns purely the sound you make when you talk, your pronunciation. Since everybody has a pronunciation of their language, everybody has an accent. Those people who say that somebody ‘doesn’t have an accent’ either mean that the person concerned sounds just like they do themselves, or means that the accent used is the expected one for standard speakers to use. In either case, there is an accent. The accent in which Southern Standard British English is typically spoken, sometimes called ‘BBC English’, is usually termed ‘Received Pronunciation’ or ‘RP’ by linguists.

Do not be confused by English spelling. It does not always match the pronunciation. If you have learned English from books and the written word, it is very important for you to stop thinking about words from the way they are written. English spelling comes from many different places. It is not consistent!

Accent is composed by four elements. Voicing. Voicing means where your voice comes from. Some languages come from the nose, some come from the throat, and some come from the chest. Rhythm and Intonation. Rhythm and Intonation show the “music” of the language. Every language has its own patterns of pitch, beat, and speed. Word Connections/Liaison. A liaison is a French word that means connection. All words in a sentence get connected together to make it smooth. Remember that everything is linked together, for instance we connect: consonants with vowels. Pronunciation. Pronunciation (also called articulation) is the sound of the vowels and consonants. They are made by the placement of the tongue, teeth, lips and vocal cords.

Stress. English has 3 (sometimes 4) kinds of stress. The sounds that you hear go up the most are called Primary Stress. Every content word has one primary stress. A lot of words have a Weak Stress. The Weak Stress is most often a schwa and sometimes a very shortened vowel. There is a major or primary stress in every content word (nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs.) These words often contain secondary and weak stresses as well. All other words are usually reduced, or weakened. These include prepositions, articles, conjunctions, auxiliary verbs, Be verbs, etc. To weaken them we shorten their vowels or turn them into a schwa sound. Because they are short, they sound fast. We also stress words when we contrast them against one another.

George Bernard Shaw noted it a century ago. “It is impossible for an Englishman to open his mouth without making some other Englishman hate or despise him,” the Irish playwright observed in his preface to Pygmalion. The seminal play – which was later remade into the musical My Fair Lady and for Hollywood audiences as the film Pretty Woman – was Bernard Shaw’s sharp commentary on the English class system. At its heart was an acknowledgement that the tone of what the English say is a greater predictor of their success and status than the content. Shaw wrote Pygmalion in 1916, and little has changed.

The island of Great Britain manages to squeeze a huge breadth of accents into a relatively small geographical area. Some accents are beneficial, others detrimental. Research by the sociolinguist Professor Devyani Sharma, from the University of London, reveals that Received Pronunciation (cut-glass Queen’s English) continues to be a predictor of success. So too does French-accented English and a gentle Scots lilt from Edinburgh and environs. By contrast, ethnic-minority accents like Indian English are a hinderance, as are strong regional accents like Brummie (from Birmingham), Scouse (from Liverpool), Cockney (from east London) and the Estuary English of Essex and Kent.

Americans might find our preoccupation with accents quaint. But it is much more than an English eccentricity: it is actively damaging. Accent-bias is arguably seen as the last “forgivable” prejudice. Yet in truth it is unforgivable: leaders have a responsibility to convey to our teams how ridiculous such biases are.

Language is an instrument of society, used for purposes of social cooperation and social intercourse. It must of its nature be tightly linked at many points to the structure of the community in which it operates, and it must therefore be capable to some extent at least of serving as an index of groups and attitudes within that community. So far as pronunciation is concerned, we are aware that it characterizes geographical areas in the form of regional accents and perhaps classes within those areas by modification of the accent, but we really have very little knowledge about even these apparently obvious connections and no general theory to enable us to give a coherent account of the relation between differences of pronunciation and differences of social grouping and social attitudes.

Studies of regional pronunciations have been of two kinds: a survey of differences over a larger or smaller area, and a study of the pronunciation of a particular place as exemplified by the speech of one or a small number of native speakers, usually old, so that the older form of the accent shall not die out unrecorded. The broader survey is liable to concentrate on difference of pronunciation in a necessarily limited number of words and to fail to make it plain whether these differences are systemic or not; the narrow one cannot guarantee that the characteristics it finds are necessarily typical of the place as a whole, with all the speakers of different age groups and social positions that it contains.

What we need, therefore, to fill in large gaps in the picture are area surveys designed to study the systems and not merely the realizations found at different places; and at the same time some attempt to characterize in a broader way the situation regarding pronunciation in a particular place. Urban accents have been largely neglected in favour of rural ones, yet it is surely of interest to know just what the situation is in the cities and towns where the bulk of the population lives, and to know just what amount of variety there is, ranging from the most characteristic form of the accent to very modified forms. And the picture would certainly not be complete without some attempt to relate pronunciations to age and social or economic status, and to note what, if any, changes take place with changes in age and status.

By selecting key features of pronunciation both systemic and non-systemic, and following them through the social and age range, we would get a soundly based view of the social implications of accent, which we all know to exist and to be important in British life, perhaps more than elsewhere. Linked with this is the question of accent and prestige: within a particular accent, does one form of pronunciation carry greater prestige than others, and what social factors is this linked to? And more generally what is the attitude of speakers of all social back-grounds and all accents to their own and other accents? Is the prestige of RP declining amongst younger speakers? There is some reason to think so, but all this needs putting on a firm, statistical basis so that we have something more than each individual’s impression to go on.

It is sometimes thought that regional accents are on the point of dying out, of being levelled into one common accent, but this is to misconceive the whole position. Accents change, no doubt, but they do so slowly and they do not necessarily move towards the same centre. The fear – and it generally is a fear rather than a joyous prospect – that local accents are being eliminated usually stems from a belief that RP is likely to take them over through being heard more often than other accents on radio, television and film.

There is at present no firm evidence that this is happening or likely to happen, so we can settle down to gathering the sort of evidence which would throw light on the situation, without feeling the hot breath of imminent disappearance on our necks. A connection has often been made between pronunciation and occupation, but again on a rather impressionistic basis. We are all aware of the existence of something called the “clerical voice”, even if we only hear it in low comedy; the salesman may be characterized as “a fast talker”; politicians often use the same features of pronunciation, at any rate in their public utterances; barristers similarly.

There is certainly something in it, but how much? This is a question which can again only be answered by looking for evidence, and we can be sure that we will not find that every single politician or every single barrister has even one feature in common with all his fellows which marks him off from the rest of us. The situation will be much less cut and dried than that and we will need to develop methods which enable us to deal with gradations of occupational marking by pronunciation. These are questions of social role, but each of us plays a variety of roles and again these differences are often marked by pronunciation.

We adapt ourselves to social situations in our manner of speech as well as in our matter; our pronunciation is not the same in a relaxed, friendly conversation as in an interview for a job or in saying prayers or in making a speech. It may be appropriate to pronounce I don’t know as [ado’nou] in informal conditions or as [adoo’nou] or [ai’dount’nou] or even [ai ‘du: npt ‘mu] as formality increases (and notice too that the last pronunciation quoted is much more likely to be heard from an American than a British speaker, which is itself of considerable significance).

Stylistic variations of this kind have been commented upon from time to time ad hoc, but no systematic investigation has yet been carried out even for one person’s speech. It has also been suggested that the pronunciations of men and women differ within the same accent and the same social group. The reason advanced is that in Britain at any rate women are more sensitive to “correctness” in speech and that their pronunciation is therefore somewhat different from men’s in the direction of what they take to be more desirable. Again there is probably something in this idea, and just how much there is in it could be established by investigation.

Most people, when they talk about pronunciation, talk about it purely in terms of correctness, of what is “right” and what is “wrong”, what “good” and what “bad”. The only kind of question a phonetician ever gets asked by his non-phonetic friends is “Which is best, /ˈiːðə(r)/ or /ˈaɪðə(r)/ and this is difficult because the correct (and quite unacceptable) answer is “It all depends.” In fact, the answer can only be a social one: what is correct depends upon what group you are talking about and what the preponderant pronunciation in that group is. So in most American or N. English groups the pronunciation /ˈiːðə(r)/ for either is correct in the sense that it is by far the most common one.

In RP on the other hand /ˈaɪðə(r)/ is correct for the same reason. It is this social form of correctness which is operating when people change their pronunciation according to their environment, why a Yorkshire-man who comes South starts to pronounce glass as /gla:s/ instead of /glæs/ or an Englishman in the United States may pronounce fertile to rhyme with turtle or lever to rhyme with never. It is a process of adaptation to or identification with a particular social group and it seems clear that some people adapt more quickly and more completely than others in pronunciation, and no doubt in other linguistic and extra-linguistic ways.

It would be very interesting if we could work out an adaptability scale, ranging in theory from total independence from environment at one end to complete adaptation at the other; if we were then able to relate an individual’s adaptability quotient for pronunciation to other factors such as personality traits or social attitudes it might provide a useful tool for investigating such matters. Before we dismiss the notion of correctness as purely an aspect of social adaptation we must take into account that when someone asks “Is this or that correct?” he usually has at the back of his mind the idea of prestige.

One pronunciation carries more kudos with it than another, and there may be a certain amount of one-upmanship involved in using, say, the pronunciation for either in a group where it is predominantly. The disentangling of these two strands, adaptation and prestige, in the idea of correctness, presents a complicated problem, and solving it would require the cooperation of the phonetician, the psychologist and the sociologist, but if it were solved we should understand more deeply the way in which not only pronunciation but language as a whole is used and the way in which its users regard it.

Britain provides a particularly rich field for this kind of research because pronunciation and social class are intimately linked. It is often said that in, for example, Germany or indeed the United States, very much less prestige attaches to one or several types of pronunciation, and that a speaker is not placeable socially by his pronunciation to the same extent as in Britain. Before this can be stated definitely we will have to undertake the same sort of research in other countries to elicit typical patterns of attitude and of relations between accent and social groups.

From the point of view of social justice it is very sad that one pronunciation should confer social advantage or prestige and that another should bear a stigma. It would be much more equitable if we could all pronounce in our native way with no feelings of guilt or smugness, of underdog or overdog. However, language does not itself shape society, rather the reverse, and in language, particularly in pronunciation and the attitudes it evokes, we may see a faithful reflection of the society in which we live. If it is true, as we surmised earlier, that younger speakers pay less attention to correctness and prestige in pronunciation this may well be a sign, and a welcome one, of change in our social attitudes.

Regional British Accents!

35 Accents in the English Language

50 People Show Us Their States’ Accents