Wales! Wales! Home sweet home is Wales Till life is past My love shall last My longing, my hiraeth’ for Wales. The land of my fathers, the land of my choice, The land in which poets and minstrels rejoice: The land whose stern warriors were true to the core While bleeding for freedom of yore .

Wales Wales Home sweet home in Wales Till life is past My love shall last My longing, my hiraeth for Wales.

Land of My Fathers The Welsh National Anthem

Wild Wales has never been a nation in the same way that England has been. Like the Celts of Ireland, the Welsh were rural people who lived in wandering tribes, headed by chieftains who were usually at war with one another. There has never been a proper centre to Wales and in fact the country had no capital city until 1955, when Cardiff was chosen, only because of its size.

The Welsh Celts were the inhabitants of Britain long before the invasions of the Romans, the Anglo-Saxons and the Normans. They had come from the Iberian peninsula and probably felt at home at once, for the landscape of rugged Wales is remarkably similar to the green mountainous regions of Northern Spain and Portugal. Even today the origins of the Welsh can be detected by their being shorter, darker and stockier than their Anglo-Saxon neighbours.

Of course Wales, like Scotland and Ireland, is an English speaking country, but the Welsh have been more successful than their Celtic cousins in retaining their original language and today some 20% of the population are bi-lingual in Welsh and English. Most of the lovely Welsh folk songs are generally sung in the Welsh language, but fortunately for us they usually have English words as well so that we can understand them.

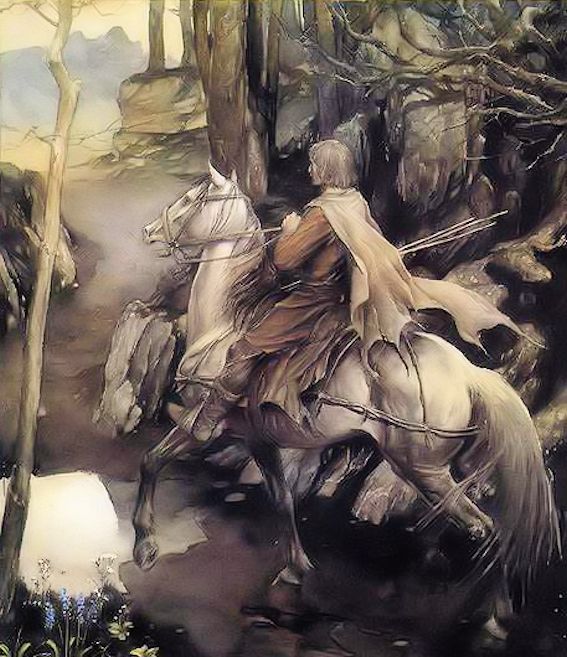

Like all Celtic countries, Wales is a land of legends and the Welsh have their own national heroes, most of them famed for fighting the hated Saxon invaders. Two mediaeval princes, Llewellyn the Great and Llewellyn the Last, stand out as champions of Welsh independence. Stories of their attempts to unify Wales and free the country from English rule are well known to Welsh schoolchildren, but one sad story concerning Llewellyn the Great’s dog, is more widely known and freely told to anyone travelling through Snowdonia, the beautiful mountainous region of North Wales.

Once upon a time in a lovely valley near our highest and most sacred mountain, Snowdon, there was a fine palace in which lived Llewellyn, the Prince of North Wales. He had a wonderful, beautiful, faithful dog called Gelert who went everywhere with the Prince, always at his side. One day the Prince was going out hunting and Gelert, of course, expected to go with him, but Llewellyn instead ordered the dog to stay at the palace and guard his baby son. Gelert was disappointed as he loved hunting with his master, but he obediently lay down beside the baby’s cradle and Llewellyn went off.

That evening, when the Prince returned home, Gelert came running out to greet him. Llewellyn was horrified to see that the dog was covered with blood and there was blood dripping from the dog’s mouth too. The Prince rushed into the palace and found the baby’s cradle empty. Wild with grief and rage, thinking that his dog had killed his son, Llewellyn drew his sword and plunged it into the heart of his dog. As Gelert fell dying at his master’s feet, the Prince heard the crying of a baby.

Frantically searching the room he found the baby safe and unhurt under a pile of blood-stained blankets. Next to the blankets he discovered the body of a huge wolf that Gelert had killed defending the baby. Llewellyn rushed back to his dog’s side, but found that the faithful friend was dead. The Prince was so overcome with sorrow that it is said he never smiled again. He buried the dog on the very spot where he died and to this day the village that grew up in that green peaceful valley is called Beddgelert, which in our Welsh language means “The Grave of Gelert”.

Traditional Welsh Legend

Another legend, famous throughout Britain, is the story of the creation of the first Prince of Wales. After years of fighting, King Edward I of England finally conquered Wales. Llewellyn the Last had been killed and the Welsh were without a leader. Edward wanted to make a gesture of friendship and reconciliation to the Welsh people so he promised them that they would be ruled by a Prince who was born in Wales, of royal blood, who could speak neither English nor French and with a spotless character that no man could truly speak against. In 1248 the King assembled the Welsh chieftains at Caernarvon, where he and his wife Eleanor had been staying for some time during the construction of a great castle – the most magnificent in Britain. To fulfil his promise he proclaimed as Prince of Wales his baby son – born one week earlier in Caernarvon Castle, of royal blood, unable to speak English or French and of a character no one could speak against. Edward – Prince of Wales.

The chiefs were angry and disappointed that one of them had not been chosen, but the Welsh people accepted the King’s son as their Prince and since that time it has been the tradition for the King of England’s eldest son to become Prince of Wales. In 1958 Queen Elizabeth II made an historic announcement during the Commonwealth Games held in Cardiff: “I intend to create my son Charles Prince of Wales today. When he is grown up I will present him to you at Caernarvon”.

“I remember sitting in the Headmaster’s study at Cheam. And we were all watching television, and there were several other boys there, little ones, and I remember being acutely embarrassed when it was announced, and I heard this marvellous great cheer coming from the stadium in Cardiff, and I think for a little boy of nine it was rather bewildering.

H.R.H. Prince Charles The Prince of Wales

Although the first Princes of Wales were entirely of Saxon blood, intermarriage between English and Welsh royalty gave later Kings of Britain the legitimate right to the title, by virtue of their Welsh ancestry, and Prince Charles can claim descent from many of the early Welsh Princes, including Llewellyn the Great and Llewellyn the Last. In this age of nationalism, the present Prince of Wales prudently took a course in the difficult Welsh language at Aberystwyth University so that he could speak to the Welsh in their ancient tongue.

Even so, Welsh nationalists staged many demonstrations against Prince Charles, seeing him as a symbol of English oppression of the Welsh people. The young Prince’s reaction to one such demonstration outside the Welsh office in Cardiff is recalled by a prominent Welshman, George Thomas, now Speaker of the House of Commons, but then Secretary of State for Wales: “And he said to me ‘Who are they?’ ‘Oh, they’re protesters,’ I said. He said ‘I’m going to talk to them.’ ‘Very unwise’,’ I said. ‘I don’t think you ought to.’ ‘I’m going to talk to them,’ he said. Well, you don’t argue with the Prince of Wales when he says that, so all I said was, ‘Well, I’m coming with you.’ You know, he showed remarkable courage, he wasn’t twenty then. He wasn’t twenty. And when we went outside he crossed the road, and I suppose there were about a hundred, that’s all, but they were very noisy. And he dived in at the six-foot-end, started to chat with them. He… they were laughing before he left them. He’s got a very great gift for disarming people. It’s a marvellous gift for anyone in public life.”

The formal investiture of the Prince of Wales took place in Caernarvon in 1969. On the same spot where her ancester King Edward I had presented his son as the first Prince of Wales more than 500 years before, Queen Elizabeth gave the Welsh people their 21st Prince of Wales in the great tradition of British royal pageantry.

Among our ancient mountains And from our lovely vales,

Oh let the prayer re-echo, God bless the Prince of Wales.

With heart and voice awaken Those minstrel strains of yore,

Till Britain’s name and glory Resound from shore to shore.

Among our ancient mountains And from our lovely vales,

Oh let the prayer re-echo God bless the Prince of Wales.

God Bless the Prince of Wales.

Words by George Linley Music by Brinley Richards

Now the Welsh people have taken to their hearts the new, beautiful, young Princess of Wales. “I do hope that bore some relationship to what I meant to say, which is basically that it is a very great pleasure to me to come to Wales and to its capital, Cardiff. I look forward to returning many times in the future, and also I’d like to just add how proud I am to be Princess of such a wonderful place and the Welsh people who are very special to me. Thank you.

H.R.H. The Princess of Wales accepting the freedom of the City of Cardiff 1981

Between the first Prince of Wales and the present Prince of Wales there have been outbreaks of Welsh rebellion from time to time against the Kings of England, usually at times when the English throne was particularly weak. In the 15th century, a Welsh patriot called Owen Glendower led a campaign for Welsh freedom and independence, fighting against his one-time friend, King Henry IV. The national revolt was, for a time, enormously successful. Owen Glendower actually set up a Welsh national Parliament at Harlech, proclaimed himself the rightful Prince of Wales, a title that was recognized on the Continent, set up an independent Church, nominating his own Bishops, and secured military support from France. It was his misfortune that he was required in time to face the greatest soldier of the day, Henry IV’s son, the true Prince of Wales, who later became the legendary Soldier-King Henry V, whom you will remember defeated the French at Agincourt and married the Princess Katherine of Franca. Although Owen Glendower was defeated the magic of his name and his cause continued and he is today in Wales considered the greatest Welshman in history, and the man who came closest to making Wales a unified independent country.

Harlech Castle, which had been the site of the last Welsh Parliament, was the scene of fierce fighting during the Wars of the Roses and only after a blockade and after a great slaughter did the fortress finally fall to King Edward IV. The defence of Harlech was commemorated in a famous song now known all over the English speaking world:

Men of Harlech, are ye waking Saxon hosts your hills are shaking,

Proudly now your swords be taking, Gather in your might.

Hark, a thousand voices call ye, Let old hero hearts enthral ye,

Shall the thought of death appal’ ye? Hasten to the fight!

With the trumpet sounding, Wildly now be bounding,

Onward go to meet the foe, The tyrant band surrounding;

Your ancient banners waving o’er ye, Rank on rank fall back before ye,

March to victory, march to glory, Harlech, show your might!

Rhyfelgyrch Gwyr Harlech

Men of Harlech (English words by Edward Lockton) Music: Cilmeri

The bardic tradition in Wales goes back to the Druids – when contests were held and prizes given for the finest poetry and songs. These meetings, called Eisteddfods, are still being held all over Wales, and once a year there is a grand National Eisteddfod where all the bards and minstrels gather to compete for the top honours in poetry and music. The famous old Welsh song you are about to hear tells the story of one of the ancient bards – David of the White Rock.

David the bard on his bed of death lies, Pale are his features and dim are his eyes.

Yet all around him his glance wildly roves, Till it alights on the harp that he loves.

Give me my harp, my companion so long, Let it once more add its voice to my song.

Though my old fingers are palsied and weak, Still my good harp for its master will speak.

Dafydd y Gareg Wen David of the White Rock (English words by John Oxenford) Ancient Welsh melody

From the ancient book of Welsh mythology, The Mobinogion, comes the unusual name “Dylan” which, appropriately, was given to a 20th century bard who wrote in English, and is generally considered Wales’ greatest poet. Dylan Thomas.

Dylan Thomas was born in Swansea, in South Wales, in 1914, and wrote much of his finest poetry at an early age. He also wrote prose and short stories, and one of his best loved works is based on his own childhood in Swansea, in which he captures the humour and the colourful speech of the Welsh

Wherever Welshmen are together, there will be singing, for Wales is the land of song, and nothing is more typical of Welsh music than the male choir.

While the moon her watch is keeping, All through the night,

While the weary world is sleeping, All through the night.

O’er my bosom gently stealing, Visions of delight revealing,

Breathes a pure and holy feeling, All through the night.

Ar Hyd Y Nos, Traditional Welsh Melody, English words by T. Oliphant

The Welsh are famous for producing singers, from popular artists like Shirley Bassey and Tom Jones to great opera stars like the soprano Gwyneth Jones and Sir Geraint Evans, but they are equally famous for producing great orators, from local preachers in the Methodist or Baptist chapels, to high ranking politicians. One of the most famous of these orators was the Welshman who became Britain’s Prime Minister during the First World War, David Lloyd George. Like Dylan Thomas, he was the son of a schoolmaster, and with his great gift for speech-making, he rose from a penniless lawyer to the highest post in the land.

“The stern hand of fate has scourged us to an elevation where we can see the great everlasting things that matter for a nation; the great peaks of honour we had forgotten – duty and patriotism clad in glittering white: the great pinnacle of sacrifice pointing like a rugged finger to heaven.” from a speech made by David Lloyd George, 1914 Prime Minister of Great Britain 1916-1922

David Lloyd George has been called the architect of the allied victory in the Great War – a war which all but annihilated the most talented youth in Europe. Two of the finest poets who wrote about the war, Edward Thomas and Wilfrid Owen, were both Welsh and were both killed in action as young soldiers. Their poetry, however, survives and here is one of the finest poems of the period: Wilfrid Owen’s Anthem for Doomed Youth.

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?

Only the monstrous anger of the guns.

Only the stuttering’s rifles’ rapid rattle

Can patter out their hasty orisons.

No mockeries for them from prayers or bells,

Nor any voice of mourning save the choirs –

The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells;

And bugles calling for them from sad shires.

What candles may be held to speed them all?

Not in the hands of boys, but in their eyes

Shall shine the holy glimmers of good-byes.

The pallor of girls brows shall be their pall;

And each slow dusk the drawing-down of blinds.

Anthem for Doomed Youth by Wilfrid Owen

The Industrial Revolution in England changed the face of Wales from a pastoral country to a land of coal mines. The demand for Welsh coal and other minerals brought a certain prosperity and created jobs for miners, but it also brought new problems. In 1966, a coal slag-heap collapsed onto a school house in Aberfan killing nearly every child in the village. Explosions and mine disasters have been common, and nearly every mining village can claim casualties that are an occupational hazard in working underground. The children of these villages were usually poorly educated and sent to work in the mines as soon as the law allowed it. Vernon Watkins, a Welsh poet who was a contemporary and friend of Dylan Thomas, paints a gloomy picture of a child destined for a life of toil in the dark mine shafts, in his poem The Collier.

When I was born on Amman hill

A dark bird crossed the sun.

Sharp on the floor the shadow fell;

I was the youngest son.

And when I went to the County School

I worked in a shaft of light.

In the wood of the desk I cut my name:

Dai for Dynamite.

The tall black hills my brothers stood;

Their lessons all were done.

From the door of the school when I ran out

They frowned to watch me run.

The slow grey bells they rung a chime

Surly with grief or age.

Clever or clumsy, lad or lout.

All would look for a wage.

They dipped my coat in the blood of a kid

And they cast me down a pit,

And although I crossed with strangers

There was no way up from it.

Soon as I went from the County School

I worked in a shaft. Said Jim.

“You will get your chain of gold, my lad,

But not for a likely time.

from The Collier by Vernon Watkins

But some children were lucky enough to escape the dreary life of the Welsh mining community, with only rugby football, religion and singing in the local choir to relieve the boredom and poverty. There is, in fact, a tradition of the bright child who by luck or ambition, gets a good education and rises to a position of fame and fortune in Britain. George Thomas, Speaker of the House of Commons and a Baptist preacher, was just one from such a background.

Here he tells about an exchange he had with the Prince of Wales:

“I remember saying to Prince Charles once: ‘Do you remember, Prince Charles, you’re the son of a monarch; I’m the son of a miner. I grew up in a miner’s cottage without a bathroom, and you grew up in a palace.’

And he looked me straight in the eyes, mind, straight in the eyes; he said. ‘Well, what about it?’ Because I could tell already and that… when he was… he wasn’t twenty-one… that he had his values, and he obviously felt… it’s what people are, and what people do that’s more important than what they’re called.”

Another son of a poor Welsh miner was a boy called Richard Jenkins. His schoolmaster Philip Burton gave him the backing he needed for an Oxford education and gave him a new name for his career in the theatre and films – Richard Burton.

Find out more reading the following articles: