Christ with me, Christ before me, Christ behind me, Christ on my right, Christ on my left, Christ when I lie down, Christ when I arise…Christ in every eye that sees me, Christ in every ear that hears me.

Saint Patrick (c. 389 – 461)

Saint Patrick’s Day or St. Patrick’s Day, holiday honoring Saint Patrick, the patron saint of Ireland. It is celebrated annually on March 17, his feast day. Saint Patrick was a missionary in the 5th century ad who is credited with converting Ireland to Christianity. St. Patrick’s Day is a national holiday in Ireland. It is also celebrated by people of Irish descent in many other countries, especially by Irish Americans in the United States.

One popular St. Patrick’s Day tradition is wearing green clothing. Green, the national color of Ireland, symbolizes the island’s lush landscape. The main symbol associated with the holiday is the shamrock, a small three-leafed clover or clover-like plant. According to legend, St. Patrick used the shamrock, because of its three leaves, to explain the Christian doctrine of the Trinity to the Irish people. The shamrock is now the national emblem of Ireland.

The Real St. Patrick

His original name was Maewyn and he was probably born in the area we now know as Wales. Thought to have brought Christianity to Ireland he was actually a pagan until he was at least 16 years old. These are just two of the contradictions to be found in the life of Ireland’s patron saint. Barry Keane unravels the facts from within the myth.

The story of Saint Patrick begins on the shores of the Bristol Channel in Roman England in the 5th century AD, where he and many other unfortunates were captured by the powerful Irish King, Niall. According to the saint’s own account, a great many people were captured on this raid. Patrick, now a slave in Ireland, was sold to a landowner and made to tend flocks upon the weather beaten mountains of modern day County Mayo. This was to be his fate for the following six years, until one night he heard a voice in a dream telling him to escape.

Patrick walked two hundred miles until he came to a ship, but was denied passage because he “refused to ‘suck the nipples’ of the captain”, a rather strange pagan gesture of loyalty. We can conjecture here that the captain was looking for a permanent crew member, but somehow or other Patrick managed to persuade the captain to take him on board and return him to his home across the sea. He did not stay long, however, but went to study for the priesthood in France.

When he had completed his studies, Patrick went to visit relatives back in the border area between England and Wales, and it was there, he tells us, that he had a dream. He dreamt that a letter was given to him by a messenger entitled The Voice of the Irish, asking him “to walk among them.” So compelling was the dream that he determined to embark on a mission to convert the Irish to Christianity. It was a mission that would occupy the next thirty years of his life, right up until his death.

From the first, Patrick was extremely shrewd in his dealings with the structures of power that operated in Ireland at the time. The most famous instance of this is how, one night, Patrick lit a Paschal fire within sight of the hill of Slane, where King Laoghaire of Tara was presiding over a pagan feast. The king was greatly angered as the law declared that on that night no fire should be lit before the king himself had done so. The druids warned Laoghaire that if the fire was not put out that night, “it would never be extinguished.”

Laoghaire had Patrick and his followers fetched and brought to him. This led to a trial by fire between Patrick and the druids of the king’s court, whereby both sides attempted to prove the superiority of their powers. According to legend, the cloak of the druid was placed about a follower of Patrick named Banignus and set alight. Benignus’ faith kept him free from the flame even though it burned to ashes all around him.

When the cloak of Benignus was placed around the druid and set alight, the druid, despite his incantations, suffered a horrible death before the eyes of his king, With the death of the druid, Patrick declared that those present had witnessed the beginning of the end of paganism in Ireland, whereby he made a deal with Laoghaire that he could preach in his territory without being killed.

Confession

In his autobiographical work, Confessio, Patrick does not tell us of the pagan belief system that he encountered during his mission, but many subsequent folk legends tell of his continuous warring with the druids of Ireland, who had up till that time served a religious and political function that may have even been more powerful than the kings themselves. Celtic druids were, for the main part, magical advisors to the kings, who acted as intermediary personages between this world and the next. The triumph of Christianity would spell the end of the recognition of the magical practices and spiritual power as practised by the druids. That they fought the ascendancy of Patrick’s teachings every step of the way is borne out by the numerous stories recorded by both Patrick and his biographers of how the druids tried to murder him.

Much of the success of Patrick’s mission can also be put down to his own reasonableness and sensitivity when dealing with Ireland’s pagan tradition. Attaining happiness in the afterlife in Christian teaching was only achievable in Christ, which, of course, meant that Patrick would in theory have had few words of hope to offer new converts concerning the fate of their deceased pagan family members. However, there is a high probability that the saint instituted the practice of resuscitating the dead (perhaps ritually, at least), baptizing them and once again laying them to rest. One story, recounted by Patrick’s biographer, Tireachan, tells how Patrick once came across a large grave. His followers marveled at the sight and declared that men of such stature no longer existed. With that, Patrick struck the grave stone with his staff and made the Sign of the Cross. Like an episode from Homer, the dead man suddenly arose and said that he had been killed by a band of warriors. Patrick baptized him and returned him to the grave once again.

Worship of the sun and solar power was common throughout the pagan world. Indeed, it formed the cult centre of Constantine’s reign prior to his embracing of Christianity. For Patrick, benevolence and all things good were made possible only by the grace of God. He, therefore, made a special effort to differentiate between natural light and that of the inner light of God. The sun only rose in the sky, preached Patrick, because God willed it to be so.

This position struck at the heart of Celtic pagan rites and teaching, and particularly problematic proved to be the worship of deities such as Lugh, associated with light (Latin lux – light), and celebrated at the harvest festival of Lughnasa. Over the centuries, however, pagan seasonal festivals soon came to be associated with Christian calendar events. Indeed, Lughnasa in the middle ages was associated with Patrick’s victory over paganism, whereas Samhain, a festival of the dead celebrated at the beginning of Winter, became appropriated by Christianity’s All Souls Day.

Patrick laid strong foundations for a process that would take centuries to complete. And but a few centuries later, Ireland would become Europe’s centre of monasticism and a beacon of light in a European world that had suddenly become terribly dark. Christianity in Ireland came at a price, however, as it necessitated the death of a belief system that seems to us today to have been perfectly in tune with both nature and the otherworld. Having said that, Ireland can count itself fortunate indeed that a man such as Patrick managed to introduce a revolutionary concept to an ancient land whilst also endowing the word of Christ with a distinct Celtic character.

Legends

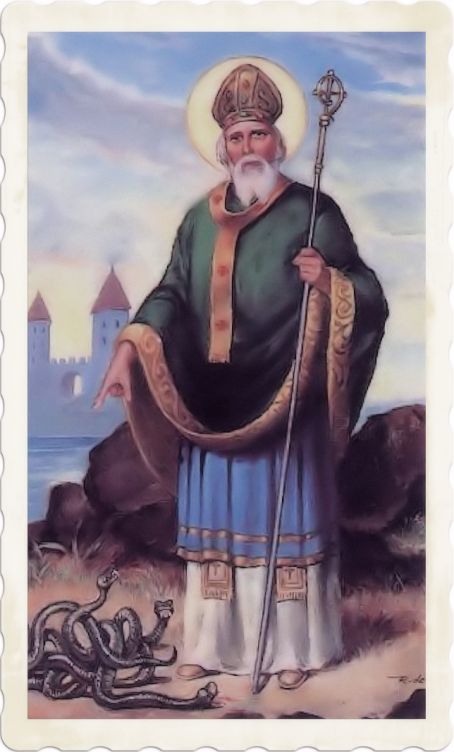

Before the end of the 7th century, Patrick had become a legendary figure, and the legends have continued to grow. One of these would have it that he drove the snakes of Ireland into the sea to their destruction. Patrick himself wrote that he raised people from the dead, and a 12th-century hagiography places this number at 33 men, some of whom are said to have been deceased for many years. He also reportedly prayed for the provision of food for hungry sailors traveling by land through a desolate area, and a herd of swine miraculously appeared.

Another legend, probably the most popular, is that of the shamrock, which has him explain the concept of the Holy Trinity, three persons in one God, to an unbeliever by showing him the three-leaved plant with one stalk. Traditionally, Irishmen have worn shamrocks, the national flower of Ireland, in their lapels on St. Patrick’s Day, March 17.

Ireland’s largest church, St. Patrick’s Cathedral is the national church for the Church of Ireland, a building with significance to Irish culture and a feast for eyes appreciative of ancient architecture. The place where the church now stands is believed to represent Ireland’s most ancient Christian site, where St. Patrick baptized his converts. Between the 5th century and the year 1191, the church onsite was built of wood. The present building was constructed starting in 1191 to be completed in 1270. It was in 1191 that the structure was re-classified as a cathedral.

From 1783 to 1871, the Knights of St. Patrick used the church as the Chapel of the Most Illustrious Order of Saint Patrick. Significant reconstruction works during the 1870s were undertaken when concerns over the architectural integrity of the building led to fears of collapse. Accordingly, the present day look of the building is decidedly Victorian in form due to the extent of the renovations and upgrades. Interestingly, the work was funded by Sir Benjamin Lee Guinness himself, who is commemorated with a bronze statue at the church.

St. Patrick’s Day In Ireland

Saint Patrick, known as the Apostle of Ireland, became bishop of Ireland sometime after 431. Many legends exist about his life, including that he drove the snakes out of Ireland, as is depicted here. Saint Patrick’s Day is celebrated each year on March 17.

In Ireland, St. Patrick’s Day is an important religious holiday celebrating the conversion of the Irish to Christianity. Businesses are closed, except for some restaurants and pubs. People attend church services honoring St. Patrick and learn about his life. Many Irish people wear sprigs of real shamrock and greet each other by saying, ‘Beannachtaí na Féile Pádraig oraibh,’ or ‘May the blessings of St. Patrick be with you.’ Many enjoy a traditional meal that includes colcannon – boiled potatoes and cabbage mashed together with butter. The day is also seen as a reprieve from the sober weeks of Lent, and adults may drink a pint of ale (called “drowning the shamrock”) and allow their children some candy.

Until recently, Ireland held few parades or secular celebrations on St. Patrick’s Day. However, in 1995 the government of Ireland established the St. Patrick’s Day Festival with the goal of creating a national festival “that ranks amongst all of the greatest celebrations in the world.” The four-day festival, launched in 1996 and held annually in Dublin, features a major parade on St. Patrick’s Day as well as music and dance performances, food, crafts, and a fireworks display. The event is Ireland’s largest annual celebration.

St. Patrick’s Day In The United States And Canada

Celebrating St. Patrick’s Day has been a tradition in the United States since 1737, when the Charitable Irish Society of Boston organized the first St. Patrick’s Day parade. New York City’s parade began in 1762. St. Patrick’s Day was even acknowledged by General George Washington during the American Revolution. In 1780, during the Continental Army’s bitter winter encampment in Morristown, New Jersey, Washington permitted his troops, many of whom were of Irish descent, a holiday on March 17. This event is now known as the St. Patrick’s Day Encampment of 1780.

Today, more than 100 U.S. cities hold St. Patrick’s Day parades. The parade up Fifth Avenue in New York City is the largest and most famous. The parade traditionally stops at St. Patrick’s Cathedral for a blessing of the marchers by the cardinal of New York. The St. Patrick’s Day parade in Savannah, Georgia, first held in 1824, is one of the largest and oldest in the United States. In Canada, Montréal’s St. Patrick’s Day parade, first held in 1824, is the oldest in the country. Toronto has held a large parade since 1988.

Popular St. Patrick’s Day customs in the United States and Canada include drinking beer that has been colored green, eating corned beef and cabbage, wearing shamrock pins and green clothing, and generally celebrating all things Irish. In Chicago, the Chicago River is dyed green, a tradition started in 1962.

Saint Patrick’s Day, the traditional feast day of Ireland’s patron saint observed on March 17, has evolved into an annual celebration of Irish American ethnic identity. On Saint Patrick’s Day, Irish American communities in many cities sponsor parades. Celebrants often dress in green, symbolic of the lush, green landscape of Ireland.

Bagpipers on Parade

These bagpipers march past Saint Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City on March 17, 1993, during the annual Saint Patrick’s Day Parade. Saint Patrick’s Day, traditionally celebrated in honor of the patron saint of Ireland, has become largely a nonreligious holiday in the United States.

Northern Ireland is a modern term, brought into existence by the British Parliament’s Government of Ireland Act of 1920. Before 1920 the region was referred to as Ulster. The word Ulster derives from the Ulaid, the name of one of the Celtic dynasties of prehistory. The term is a contentious one. To Irish Catholics Ulster properly means the historic nine-county northern province of Ireland. The modern six-county territory of Northern Ireland has customarily been referred to as Ulster only by Protestants.

About Ireland you can also read: