American slang is the body of words and expressions frequently used by or intelligible to a rather large portion of the general American public, but not accepted as good, formal usage by the majority. No word can be called slang simply because of its etymological history; its source, its spelling, and its meaning in a larger sense do not make it slang. Slang is best defined by a dictionary that points out who uses slang and what “flavor” it conveys. I have called all slang used in the United States “American,” regardless of its country of origin or use in other countries. In this preface I shall discuss the human element in the formation of slang (what American slang is, and how and why slang is created and used). The English language has several levels of vocabulary, standard usage comprises those words and expressions used, understood, and accepted by a majority of our citizens under any circumstances or degree of formality.

Such words are well defined and their most accepted spellings and pronunciations are given in our standard dictionaries. In standard speech one might say: Sir, you speak English well. Colloquialisms are familiar words and idioms used in informal speech and writing, but not considered explicit or formal enough for polite conversation or business correspondence. Unlike slang, however, colloquialisms are used and understood by nearly everyone in the United States. The use of slang conveys the suggestion that the speaker and the listener enjoy a special “fraternity”, but the use of colloquialisms emphasizes only the informality and familiarity of a general social situation. Almost all idiomatic expressions, for example, could be labeled colloquial. Colloquially, one might say: Friend, you talk plain and hit the nail right on the head.

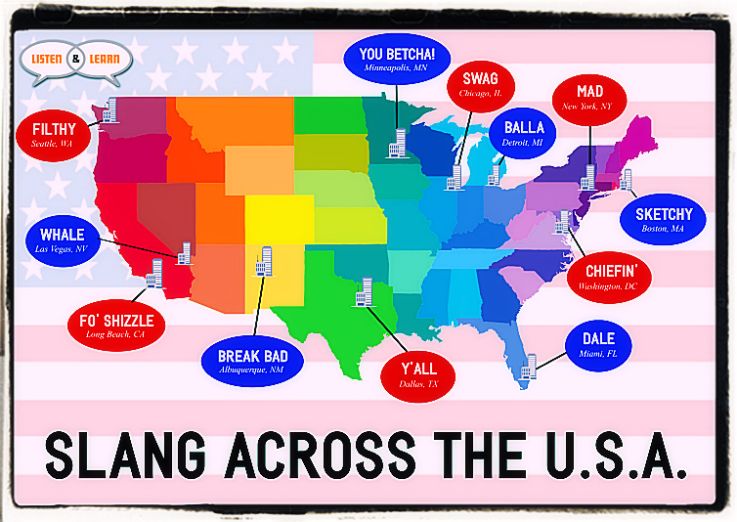

Dialects are the words, idioms, pronunciations, and speech habits peculiar to specific geographical locations. A dialecticism is a regionalism or localism. In popular use “dialect” has come to mean the words, foreign accents, or speech patterns associated with any ethnic group. In Southern dialect one might say: Cousin, y’all talk mighty fine. In ethnic-immigrant “dialects” one might say: Paisano, you speak good the English, or Landsman, your English is plenty all right already. Cant, jargon, and argot are the words and expressions peculiar to special segments of the population. Cant is the conversational, familiar idiom used and generally understood only by members of a specific occupation, trade, profession, sect, class, age group, interest group, or other sub-group of our culture. Jargon is the technical or even secret vocabulary of such a sub-group; jargon is “shop talk.” Argot is both the cant and the jargon of any professional criminal group. In such usages one might say, respectively: CQ-CQ-CQ . .. the tone of your transmission is good; You are free of anxieties related to interpersonal communication; or Duchess, let’s have a bowl of chalk.

Slang is generally defined above. In slang one might say: Buster, your line is the cat’s pajamas, or Doll, you come on with the straight jazz, real cool like. Each of these levels of language, save standard usage, is more common in speech than in writing, and slang as a whole is no exception. Thus, very few slang words and expressions (hence very few of the entries in this dictionary) appear in standard dictionaries. American slang tries for a quick, easy, personal mode of speech. It comes mostly from cant, jargon, and argot words and expressions whose popularity has in-creased until a large number of the general public uses or understands them. Much of this slang retains a basic characteristic of its origin : it is fully intelligible only to initiates.

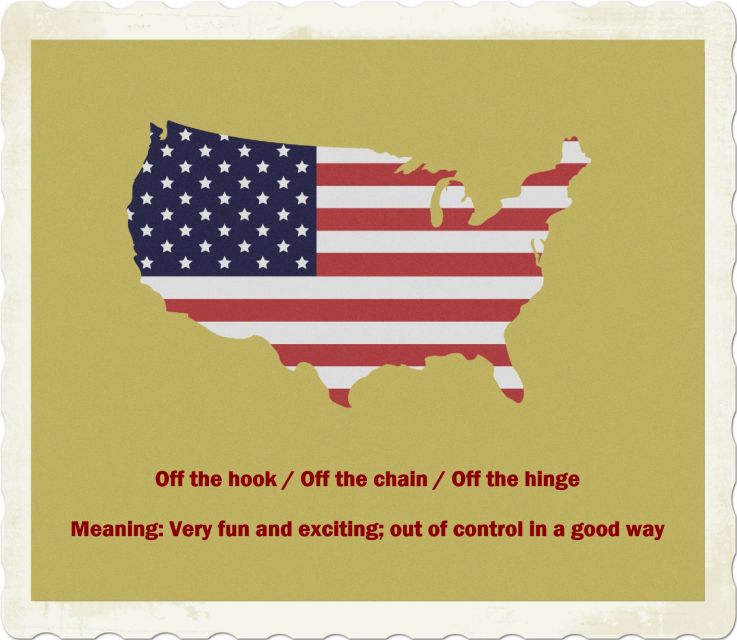

Slang may be represented pictorially as the more popular portion of the cant, jargon, and argot from many sub-groups (only a few of the sub-groups are shown below)! The shaded areas represent only general overlapping between groups:

Eventually, some slang passes into standard speech; other slang flourishes for a time with varying popularity and then is forgotten; finally, some slang is never fully accepted nor completely forgotten. O.K., jazz (music), and A-bomb were recently considered slang, but they are now standard usages. Blue-belly, Lucifer, and the bee’s knees have faded from popular use. Bones (dice) and beat it seem destined to remain slang forever : Chaucer used the first and Shakespeare used the second. It is impossible for any living vocabulary to be static. Most new slang words and usages evolve quite naturally: they result from specific situations. New objects, ideas, or happenings, for example, require new words to describe them. Each generation also seems to need some new words to describe the same old things.

Railroaders (who were probably the first American sub-group to have a nationwide cant and jargon thought jerk water town was ideally descriptive of a community that others called a one-horse town. The changes from one-horse town and don’t spare the horses to a wide place in the road and step on it were natural and necessary when the automobile replaced the horse. The automobile also produced such new words and new meanings (some of them highly specialized) as gas buggy, jalopy, bent eight, Chevvie, convertible, and lobe. Like most major innovations, the automobile affected our social history and introduced or encouraged dusters, hitch hikers, road hogs, joint hopping, necking, chicken (the game), car coats, and suburbia. The automobile is only one obvious example.

Language always responds to new concepts and developments with new words. Consider the following: Wars: redcoats, minutemen, blueb elly , over there, doughboy, gold brick, jeep. Mass immigrations: Bohunk, greenhorn, shillalagh, voodoo, pizzeria. Science and technology: gin, side-wheeler, wash-and-wear, fringe area, fallout. Turbulent eras: Redskin, maverick, speak, Chicago pineapple, free love, fink, breadline. Evolution in the styles of eating: apple-sauce, clambake, luncheonette, hot dog, coffee and. Dress: Mother Hubbard, bustle, shimmy, sailor, Long Johns, zoot suit, Ivy League. Housing: lean-to, bundling board, chuck-house, W.C., railroad flat, split-level, sectional. Music : cakewalk, bandwagon, fish music, long hair, rock. Personality: Yankee, alligator, flapper, sheik, hepcat, B.M.O.C., beetle, beat. New modes of transportation: stage, pinto, jitney, kayducer, hot shot, jet jockey. New modes of entertainment: barnstormer, two-a-day, clown alley, talkies, d.j., Spectacular. Changing attitudes toward sex: painted woman, fast, broad, wolf, jailbait, sixty-nine. Human motivations: boy crazy, gold-digger, money-mad, Momism, Oedipus complex, do-gooder, sick. Personal relationships: bunky, kids, old lady, steady, ex, gruesome twosome, John. Work and workers: clod buster, scab, pencil pusher, white collar, graveyard shift, company man. Politics: Tory, do-nothing, mug-wump, third party, brain trust, fellow traveler, Veep. Hair styles: bun, rat, peroxide blonde, Italian cut, pony tail, D.A.

Those social groups that first confront a new object, cope with a new situation, or work with a new concept devise and use new words long before the population at large does. The larger, more imaginative, and useful a group’s vocabulary, the more likely it is to contribute slang. To generate slang, a group must either be very large and in constant contact with the dominant culture or be small, closely knit, and removed enough from the dominant culture to evolve an extensive, highly personal, and vivid vocabulary. Teenagers are an example of a large sub-group contributing many words. Criminals, carnival workers, and hoboes are examples of the smaller groups. The smaller groups, because their vocabulary is personal and vivid, contribute to our general slang out of proportion to their size.

The vocabulary of the average American, most of which he knows but never uses, is usually estimated at 10,000-20,000 words. Of this quantity I estimate conservatively that 2,000 words are slang. Slang, which thus forms about 10 per cent of the words known by the average American, belongs to the part of his vocabulary most frequently used. The English language is now estimated to have at least 600,000 words; this is over four times the 140,000 recorded words of the Elizabethan period. Thus over 450,000 new words or meanings have been added since Shakespeare’s day, without counting the replacement words or those that have been forgotten between then and now. There are now approximately 10,000 slang words in American English, and about 35,000 cant, jargon, and argot words. Despite this quantity, 25 per cent of all communication is composed of just nine words. Ac-cording to McKnight’s study, another 25 per cent of all speech is composed of an additional 34 words (or : 43 words comprise 50 per cent of all speech). Scholars do differ, however, on just which nine words are the most popular. Three major studies are : G. H. McKnight, English Words and Their Background, Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc., 1923 (for spoken words only); Godfrey Dewey, “Relative Frequency of English Speech sounds,” Harvard Studies in Education, vol. IV, 1923 (for written words only) ; and Norman R. French, Charles W. Carter, and Walter Koenig, Jr., “Words and Sounds of Telephone Conversations,” Bell System Technical Journal, April, 1930 (telephone speech only). Their lists of the most common nine words are: a, and, be, have, in, is, it, on, of, etc.

Whether the United States has more slang words than any other country (in proportion to number of people, area, or the number of words in the standard vocabulary) I do not know. Certainly the French and the Spanish enjoy extremely large slang vocabularies. Americans, however, do use their general slang more than any other people. American slang reflects the kind of people who create and use it. Its diversity and popularity are in part due to the imagination, self-confidence, and optimism of our people. Its vitality is in further part due to our guarantee of free speech and to our lack of a national academy of language or of any “official” attempt to purify our speech. Americans are restless and frequently move from region to region and from job to job.

This hopeful wanderlust, from the time of the pioneers through our westward expansion to modern mobility, has helped spread regional and group terms until they have become general slang. Such restlessness has created constantly new situations which provoke new words. Except for a few Eastern industrial areas and some rural regions in the South and West, America just doesn’t look or sound “lived in.” We often act and speak as if we were sim-ply visiting and observing. What should be an ordinary experience seems new, unique, or colorful to us, worthy of words and forceful speech. People do not “settle down” in their jobs, towns, or vocabularies. Nor do we “settle down” intellectually, spiritually, or emotionally. We have few religious, regional, family, class, psycho-logical, or philosophical roots. We don’t believe in roots, we believe in teamwork. Our strong loyalties, then, are directed to those social groups – or sub-groups as they are often called – with which we are momentarily identified.

This ever changing “membership” helps to promote and spread slang. But even within each sub-group only a few new words are generally accepted. Most cant and jargon are local and temporary. What persists are the exception-ally apt and useful cant and jargon terms. These become part of the permanent, personal vocabulary of the group members, giving prestige to the users by proving their acceptance and status in the group. Group members then spread some of this more honored cant and jargon in the dominant culture. If the word is also useful to non-group members, it is on its way to becoming slang. Once new words are introduced into the dominant culture, via television, radio, movies, or newspapers, the rapid movement of individuals and rapid communication between individuals and groups spread the new word very quickly. For example, consider the son of an Italian immigrant living in New York City. He speaks Italian at home. Among neighborhood youths of similar back-ground he uses many Italian expressions because he finds them always on the tip of his tongue and because they give him a sense of solidarity with his group. He may join a street gang, and after school and during vacations work in a factory. After leaving high school, he joins the navy; then he works for a year seeing the country as a carnival worker.

He returns to New York, becomes a longshoreman, marries a girl with a German back-ground, and becomes a boxing fan. He uses Italian and German borrowings, some teen-age street-gang terms, a few factory terms, slang with a navy origin, and carnival, dockworker’s, and boxing words. He spreads words from each group to all other groups he belongs to. His Italian parents will learn and use a few street-gang, factory, navy, carnival, dockworker’s, and boxing terms; his German in-laws will learn some Italian words from his parents; his navy friends will begin to use some of his Italian expressions; his carnival friends a few navy words; his co-workers on the docks some carnival terms, in addition to all the rest; and his social friends, with whom he may usually talk boxing and dock work, will be interested in and learn some of his Italian and carnival terms. His speech may be considered very “slangy” and picturesque because he has belonged to unusual, colorful sub-groups. On the other hand, a man born into a Midwestern, middle-class, Protestant family whose ancestors came to the United States in the eighteenth century might carry with him popular high-school terms.

At high school he had an interest in hot rods and rock-and-roll. He may have served two years in the army, then gone to an Ivy League college where he became an adept bridge player and an enthusiast of cool music. He may then have become a sales executive and developed a liking for golf. This second man, no more usual or unusual than the first, will know cant and jargon terms of teen-age high-school use, hot-rods, rock-and-roll, Ivy League schools, cool jazz, army life, and some golf player’s and bridge player’s terms. He knows further a few slang expressions from his parents (members of the Jazz Age of the 1920’s) , from listening to television programs, seeing both American and British movies, reading popular literature, and from frequent meetings with people having completely different backgrounds.

When he uses cool terms on the golf course, college expressions at home, business words at the bridge table, when he refers to whiskey or drunkenness by a few words he learned from his parents, curses his next-door neighbor in a few choice army terms – then he too is popularizing slang. It is, then, clear that three cultural conditions especially contribute to the creation of a large slang vocabulary: (1) hospitality to or acceptance of new objects, situations, and concepts; (2) existence of a large number of diversified. sub-groups; (3) democratic mingling be-tween these sub-groups and the dominant culture. Primitive peoples have little if any slang because their life is restricted by ritual; they develop few new concepts ; and there are no sub-groups that mingle with the dominant culture. (Primitive sub-groups, such as medicine men or magic men, have their own vocabularies ; but such groups do not mix with the dominant culture and their jargon can never become slang because it is secret or sacred.) But what, after all, are the advantages that slang possesses which make it useful? Though our choice of any specific word may usually be made from habit, we sometimes consciously select a slang word because we believe that it communicates more quickly and easily, and more personally, than does a standard word. Sometimes we resort to slang because there is no one standard word to use.

In the 1940’s, WAC, cold war, and cool (music) could not be expressed quickly by any standard synonyms. Such words often become standard quickly, as have the first two. We also use slang because it often is more forceful, vivid, and expressive than are standard usages. Slang usually avoids the sentimentality and formality that older words often assume. Taking a girl to a dance may seem sentimental, may convey a degree of formal, emotional interest in the girl, and has overtones of fancy balls, fox trots, best suits, and corsages. At times it is more fun to go to a hop. To be busted or with-out a hog in one’s jeans is not only more vivid and forceful than being penniless or without funds, it is also a more optimistic state. A mouthpiece (or legal beagle), pencil pusher, sawbones, bone-yard, bottle washer or a course in bio-chem is more vivid and forceful than a lawyer, clerk, doctor, cemetery, laboratory assistant, or a course in biochemistry – and is much more real and less formidable than a legal counsel, junior executive, surgeon, necropolis (or memorial park), laboratory technician, or a course in biological chemistry.

Although standard English is exceedingly hospitable to polysyllabicity and even sesquipedalianism, slang is not. Slang is sometimes used not only because it is concise but just because its brevity makes it forceful. As this dictionary demonstrates, slang seems to prefer short words, especially monosyllables, and, best of all, words beginning with an explosive or an aspirate. (many such formations are among our most frequently used slang words. As listed in this dictionary, bug has 30 noun meanings, shot 14 noun and 4 adjective meanings, can 11 noun and 6 verb, bust 9 verb and 6 noun, hook 8 noun and 5 verb, fish 14 noun, and sack 8 noun, 1 adjective, and 1 verb meaning. Monosyllabic words also had by far the most citations found in our source reading of popular literature. Of the 40 words for which we found the most quotations, 29 were monosyllabic. Before condensing, fink had citations from 70 different sources, hot 67, bug 62, blow and dog 60 each, joint 59, stiff 56, punk 53, bum and egg 50 each, guy 43, make 41, bull and mug 37 each, bird 34, fish and hit 30 each, ham 25, yak 23, sharp 14, and cinch 10. Many of these words, of course, have several slang meanings; many of the words also appeared scores of times in the same book or article.) We often use slang fad words as a bad habit because they are close to the tip of our tongue.

Most of us apply several favorite but vague words to any of several somewhat similar situations ; this saves us the time and effort of thinking and speaking precisely. At other times we purposely choose a word because it is vague, because it does not commit us too strongly to what we are saying. For ex-ample, if a friend has been praising a woman, we can reply “she’s the bee’s knees” or “she’s a real chick,” which can mean that we consider her very modern, intelligent, pert, and understanding – or can mean that we think she is one of many nondescript, somewhat confused, followers of popular fads. We can also tell our friend that a book we both have recently read is the cat’s pajamas or the greatest. These expressions imply that we liked the book for exactly the same reasons that our friend did, without having to state what these reasons were and thus taking the chance of ruining our rapport. In our language we are constantly recreating our image in our own minds and in the minds of others. Part of this image, as mentioned above, is created by using sub-group cant and jargon in the dominant society; part of it is created by our choice of both standard and slang words.

A sub-group vocabulary shows that we have a group to which we “belong” and in which we are “somebody” – outsiders had better respect us. Slang is used to show others (and to remind our-selves of) our biographical, mental, and psychological background; to show our social, economic, geographical, national, racial, religious, educational, occupation-al, and group interests, memberships, and patriotism. One of the easiest and quickest ways to do this is by using counter-words. These are automatic, of-ten one-word responses of like or dislike, of acceptance or rejection. They are used to counter the remarks, or even the presence, of others. Many of our fad words and many student and quasi-intellectual slang words are counter-words. For liking: beat, the cat’s pajamas, drooly, gas, George, the greatest, keen, nice, reet, smooth, super, way out, etc. For rejection of an outsider (implying incompetence to belong to our group): boob, creep, dope, drip, droop, goof, jerk, kookie, sap, situp, square, weird, etc. Such automatic counters are overused, almost meaningless, and are a substitute for thought. But they achieve one of the main purposes of speech : quickly and automatically they express our own sub-group and personal criteria. Counter-words are often fad words creating a common bond of self-defense. All the rejecting counters listed above could refer to a moron, an extreme introvert, a birdwatcher, or a genius.

Stuart Berg Flexner

American slang dictionaries online

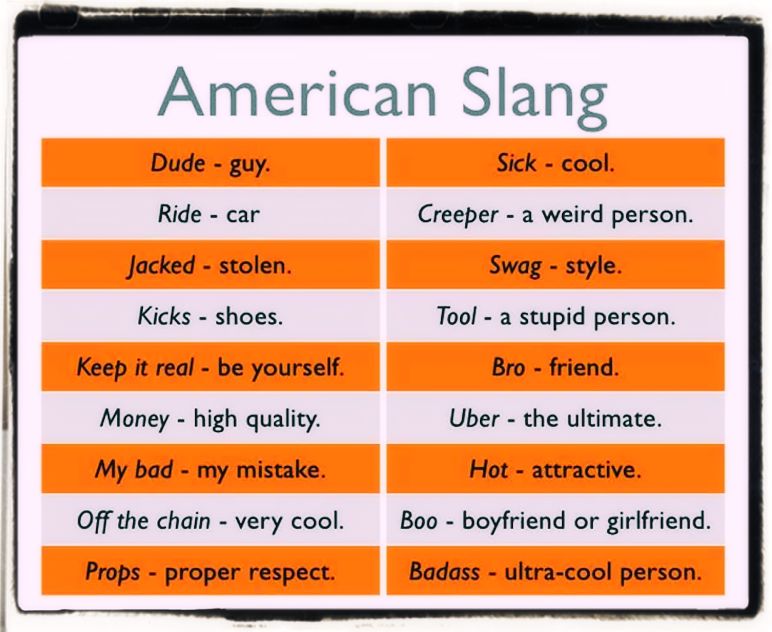

Since slang is constantly changing, it can be difficult to find definitions of certain terms in a printed dictionary. Luckily, there are many different websites offering rich collections of funny American slang words. For example:

Dave’s ESL Cafe has a short guide to American slang designed to assist those who are learning English as a second language.

Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE) breaks the U.S. into multiple regions and subregions. It only includes words that are used regionally. Audio clips are included for many words, giving you the opportunity to hear the regional slang word being said.

ManyThings has a list of more than 280 American slang definitions sorted alphabetically. Example sentences are provided with each term to make it easier to understand the correct usage.

Urban Dictionary is a large website that allows users to submit their own definitions for various slang terms. While the quality of the information can sometimes be questionable, this site is often the best resource for learning more about obscure slang usage.

Slang City, although not a dictionary in the traditional sense, is another great resource for anyone interested in learning more about American street slang. This entertaining website features articles, illustrated topical guides to various types of slang, and interactive games such as the “Random Insult Generator.”