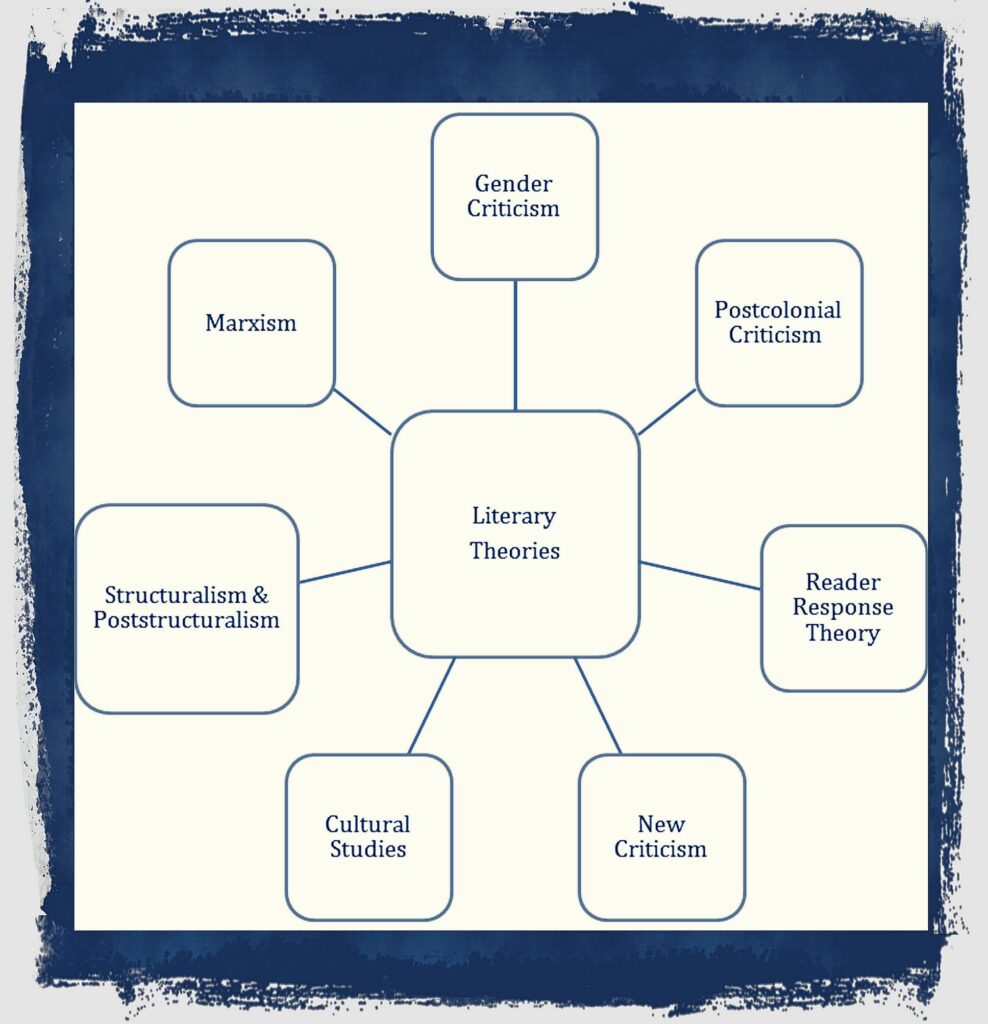

Phenomenology, Hermeneutics, Reception Theory, Structuralism and Semiotics, Post-Structuralism, Psychoanalysis, New Criticism, Pragmatism, Deconstruction Theory, Political criticism, Pluralism, and so on…

The problem with literary theory is that it can neither beat nor join the dominant ideologies of late industrial capitalism. Liberal humanism seeks to oppose or at least modify such ideologies with its distaste for the technocratic and its nurturing of spiritual wholeness in a hostile world; certain brands of formalism and structuralism try to take over the technocratic rationality of such a society and thus incorporate themselves into it. Northrop Frye and the New critics thought that they had pulled off a synthesis of the two, but how many students of literature today read them? Liberal humanism has dwindled to the impotent conscience of bourgeois society, gentle, sensitive and ineffectual; structuralism has already more or less vanished into the literary museum.

The importance of liberal humanism is a symptom of its essentially contradictory relationship to modern capitalism. For although it forms part of the “official” ideology of such society, and the “humanities” exist to reproduce it, the social order within which it exists has in one sense very little time for it at all. Who is concerned with the uniqueness of the individual, the imperishable truths of the human condition or the sensuous textures of lived experience in the Foreign Office or the boardroom of Standard Oil?

Capitalism’s reverential hat tipping to the arts is obvious hypocrisy, except when it can hang them on its walls as a sound investment. yet capitalism states have continued to direct funds into higher education, humanities departments, and though such departments are usually the first in line fos savage cutting when capitalism enters on one of its periodic crises, it is doubtful that it is only hypocrisy, a fear of appearing in its true philistine colours, which compels this grudging support. the truth is that liberal humanism is at once largely ineffectual, and the best ideology of the “human” that present bourgeois society can muster.

The “unique individual” is indeed important when it comes to defending the business entrepreneur’s right to make profit while throwing men and women out of work; the individual must at all costs have their “right to choose”, provided this means the right to buy one’s child an expensive education while other children are deprived of their school meals, rather than the rights of women to decide whether to have children in the first place…

Departments of literature in higher education, then, are part of the ideological apparatus of the modern capitalist state. they are not wholly reliable apparatuses, since for one thing the humanities contain many values, meanings and traditions which are antithetical to that state’s social priorities, which are rich in kinds of wisdom and experience beyond its comprehension. For another thing, if you allow a lot of young people to do nothing for a few years but read books and talk to each other then it is possible that, given certain wider historical circumstances, they will not only begin to question some of the values transmitted to them but begin to interrogate the authority by which they are transmitted.

There is of course no harm in students questioning the values conveyed to them: indeed it is part of the very meaning of higher education that they should do so. Independent thought, critical dissent and reasoned dialectic are part of the very stuff of a humane education; hardily anyone, as I commented earlier, will demand that your essay on Chaucer or Baudelaire arrives inexorably at certain preset conclusions. All that is being demanded is that you manipulate a particular language in acceptable ways.

Becoming certificated by the state as proficient in literary studies is a matter of being able to talk and write in certain ways. It is this which is being taught, examined and certificated, not what you personally think or believe, though what is thinkable will of course be constrained by the language itself. You can think or believe what you want, as long as you can speak this particular language. Nobody is especially concerned about what you say, with what extreme, moderate, radical or conservative positions you adopt, provided that they are compatible with, and can be articulated within, a specific form of discourse. it is just that certain meanings and positions will not be articulable within it. Literary studies, in other words, are a question of the signifier, not of the signified. Those employed to teach you this form of discourse will remember whether or not you were able to speak it proficiently long after they have forgotten what you said.

Literary theorists, critics and teachers, then, are not so much purveyors of doctrine as custodians of a discourse. Their task is to preserve this discourse, extend and elaborate it as necessary, defend it from other forms od discourse, initiate newcomers into it and determine whether or not they have successfully mastered it. The discourse itself has no definite signified, which is not to say that it embodies no assumptions: it is rather a network of signifiers able to envelop a whole field of meanings, objects and practices.

Literary criticism selects, processes, corrects and rewrites texts in accordance with certain institutionalized norms of the literary, norms which are at any given time arguable, and always historically variable. For though I have said that critical discourse has no determinate signified there are certainly a great many ways of talking about literature which it excludes, and a great many discursive moves and strategies which it disqualifies as invalid, illicit, noncritical, nonsense… The power of critical discourse moves on several levels. it is the power of “policing” language – of determining that certain statements must be excluded because they do not conform to what is acceptable sayable.

It is the power of policing writing itself, classifying it into the “literary” and “non-literary”, the enduringly great and the ephemerally popular. it is the power of authority vis-à-vis others – the power-relations between those who define and preserve the discourse, and those who selectively admitted to it. it is the power of certificating or non-certificating those who have been judged to speak the discourse better or worse. Finally, it is a question of the power-relations between the literary academic institution, where all of this occurs, and the ruling power-interests of society at large, whose ideological needs will be served and whose personel will be reproduced by the preservation and controlled extension of the discourse in question…

The final logic move in a process which began by recognizing that literature is an illusion it to recognize that literary theory is an illusion too….It is an illusion first in the sense that literary theory, as I hope to have shown, is really no more than a branch of social ideologies, utterly without any unity or identity which would adequately distinguish it from philosophy, linguistics, psychology, cultural and sociological thought: and secondly in the sense that the one hope it has of distinguishing itself – clinging to an object named literature – is misplaced. We must conclude, then, that this book is less an introduction that an obituary, and that we have ended by burying the object we sought to unearth…

The strength of the liberal humanist case is that it is able to say why dealing with literature is worth while. Its answer, as we have seen, is roughly that it makes you a better person. This is also the weakness of the liberal humanist case…

Liberal humanism is a suburban moral ideology limited in practice to largely interpersonal matters. It is stronger on adultery than on armaments, and its valuable concern with freedom, democracy and individual rights are simply not concrete enough. Its view of democracy, for example, is the abstract one of the ballot box, rather than a specific, living and practical democracy which might also somehow concern the operations of the Foreign office and Standard Oil. its view of individual freedom is similarly abstract: the freedom of any particular individual is crippled and parastitic as long as it depends on the futile labour and active oppression of others…

The idea that there are “non-political” forms of criticism is simply a myth which furthers certain political uses of literature al the more effectively. The difference between a “political” and “non-political” criticism is just the difference between the prime minister and the monarch: the latter furthers certain political ends by pretending not to, while the former makes no bones about it. it is a distinction between different forms of politics, between those who subscribe to the doctrine that history, society and human reality as a whole are fragmentary, arbitrary and directionless, and those who have other interests which imply alternative views about the way the world is. There is no way of settling the question of which politics is preferable in literary critical terms… I argued earlier that any attempt to define the study of literature in terms of either its method or its object is bound to fail. But we have now begun to discuss another way of conceiving what distinguishes one kind of discourse from another, which is neither ontological or methodological, but strategic.

This means asking first not what the object is or how we should approach it, but why we should want to engage with it in the first place. The liberal humanist response to this question, I have suggested, is at once perfectly reasonable and, as it stands, entirely useless. Let us try to concretize it a little by asking how the reinvention of rhetoric that I have proposed (though it might equally as well be called “discourse theory” or “cultural studies” or whatever) might contribute to making us all better people.

Discourses, sign-systems and signifying practices of all kinds, from film and television to fiction and the languages of natural science, produce effects, shape forms of consciousness and unconsciousness, which are closely related to the maintenance or transformation of our existing systems of power. They are thus closely related to what it means to be a person. Indeed “ideology” can be taken to indicate no more than its connection – the link or nexus between discourses and power… it is a matter of starting from what we want to do, and then seeing which methods and theories will best help us to achieve these ends.

Whatever would in the long term replace the departments of literary studies would centrally involve education in the various theories and methods of cultural analysis. The fact that such education is not routinely provided by many existing departments of literature, or is provided “optionally” or marginally, is one of the most scandalous and farcical features. Perhaps the other most scandalous and farcical feature is the largely wasted energy which postgraduate students are required to pour into obscure, often spurious research topics in order to produce dissertations which are frequently no more than sterile academic exercises, and which few others will ever read.

The present crisis in the field of literary studies is at root a crises in the definition of the subject itself… Those who work in the field of cultural practices are unlikely to mistake their activity as utterly central. men and women do not live by culture alone the vast majority of them throughout history have been deprived of the chance of living by it at all, and those few who are fortunate enough to live by it now are able to do so because of the labour of those who do not. Any cultural or critical theory which does not begin from this single most important fact, and hold it steadily in mind in its activities, is in my view unlikely to be worth very much. there is no document of culture which is not also a record of barbarism. But even in societies which, like our own as Marx reminded us, have no time for culture, there are times and places when it suddenly becomes newly relevant, charged with a significance beyond itself…

Imperialism is not only the exploitation of cheap labour-power, raw materials and easy markets but the uprooting of languages and customs – not just the imposition of foreign armies, but of alien ways of experiencing. It manifests itself not only in company balance-sheets and in airbases, but can be tracked to the most intimate roots of speech and signification. In such situations, which are not all a thousand miles from our own doorstep, culture is vitally bound up with one’s common identity that there is no need to argue for its relation to political struggle. It is arguing against it which would seen incomprehensible…

The workers writer’s movement is almost unknown to academia, and has not been exactly encouraged by the cultural organs of the state; but it is one sign of significant break from the dominant relations of literary production. Community and cooperative publishing enterprises are associated projects, concerned not simply with a literature wedded to alternative social values, but with one which challenges and changes the existing social relations between writers, publishers, readers and other literary workers.

It is because such ventures interrogate the ruling definitions of literature that they cannot so easily be incorporated by a literary institution quite happy to welcome Sons and Lovers, and even, from time to time, Robert Tressell. These areas are not alternatives to the study of Shakespeare and Proust. if the study of such writers could become as charged with energy, urgency and enthusiasm as the activities I have just reviewed, the literary institution ought to rejoice rather than complain. But it is doubtful that this will happen when such texts are hermetically sealed from history, subjected to a sterile critical formalism, pioulsy swaddled with eternal and used to confirm prejudices which any moderately enlightened student can perceive to be objectionable. The liberation of Shakespeare and Proust from such controls may well entail the death of literature, but it may also be their redemption. I shall end with an allegory. We know that the lion is stronger than the lion tamer, and so does the lion tamer. the problem is that the lion does not know it. it is not out of the question that the death of literature may help the lion to awaken.

Terence Eagleton Literary Theory An Introduction (Oxford 1983 Ed. Basil Blackwell)

Literary theory

Now in common use, like the related term poetics, amongst critics of literature to describe an approach to literature developed from the 1960s onwards which is predominantly abstract and philosophical. In principle, literary theory is distinguishable from literary criticism in that the object of focus is not the description and evaluation of individual literary texts, but the nature of literature and criticism itself. (See also metacriticism.)

In practice, however, many literary critics today, and many stylisticians also, frequently discuss works and authors from a theoretical perspective, indeed often more than one. There is no single literary theory, but several. The twentieth century saw the development of many theories arising from the discussion begun in classical poetics of the nature of literature, its aesthetic status and its features of form, for instance (see formalism). A current preoccupation today is with ethics. Literary theory has also become increasingly involved with wider ideological issues reflecting the complexity of literary activity when seen from broader intellectual perspectives. So critical theories have been drawn from disciplines such as deconstruction, Freudian psychoanalysis, feminism, Marxism and linguistics (structuralism). (See further Peter Barry 2002; Andrew Bennett & Nicholas Royle 2010).

Literary criticism

Literary criticism, still influential in literary studies in British universities today, emerged at the end of the nineteenth century and became fully established in the 1920s and the 1930s with the rise of English studies and the decline of classical studies (see Terry Eagleton 1996). The Cambridge scholars F.R. Leavis and I.A. Richards in the 1930s, and also T.S. Eliot, are particularly associated with formulating the aims and methods of literary criticism, chiefly the concentration on the critical interpretation of a canon of texts from Chaucer onwards deemed “worthy” of attention. Their ethos was predominantly humanistic: concerned with the moral and spiritual value of literary works, and their value in enacting the complexity of experience. At its heart today is the close reading of a wider range of texts, and from a variety of approaches and theories. Literary critics also discuss matters of authorship and historical, postcolonial and cultural contexts. Although some notable literary critics, following Richards (1925) and William Empson (1930), have focused attention on the language of literary texts. (see, e.g., David Lodge and Winifred Nowottny in the 1960s; and the work of Derek Attridge). Many critics have been suspicious of “stylistics” because they feel that, like linguistics, it is too “objective” and runs the risk of destroying the sensitivity of response that readers need. There is a tendency, too, fro critics to concentrate on “content” rather than “form”, and to see language as a transparent medium.

Literary pragmatics.

A term that has come into prominence in literary studies in the 1980s (sec especially Sell 1985). It follows developments in the field of linguistic PRAGMATICS (q.v.), in SPEECH ACT THEORY, TEXT LINGUISTICS and also in STYLISTICS itself, concerned with literature as DISCOURSE in its interactional and social context, and with READER reception. Hence literary pragmatics looks at the linguistic features of texts which arise from the real INTERPERSONAL relationships between AUTHOR, TEXT and reader in real socio-cultural CONTEXTS. Consideration is made of features such as DEIXIS, MODALITY, mutual knowledge, PRESUPPOSITION, politeness and TELLABILITY, etc. (See further van Dijk 1976; Traugott & Pratt 1980; van Peer & Renkema 1984.)

Literary semantics

Particularly associated with the work of Eaton (19660, who established a journal on the subject in 1971. Broadly defined, literary semantics is a branch of LITERARY THEORY (q•v•) concerned with the philosophy of LITERATURE, its value and status as knowledge, and drawing eclectically on a number of other disciplines such as PSYCHOLOGY, SOCIOLOGY and LOGIC, In a narrower sense, it is concerned, as the term semantics as well as linguistics, suggests, with the ‘meaning’ of literary TEXTS, on all levels of sound, syntax and lexis, as well as in terms of their historical context. It is also Concerned with meaning as developed in the mind of the READER While reading.

From a Dictionary of Stylistics by Katie Wales Longman 1990