Christmas in Italy, traditions, customs, habits, markets, an article that explains all about the Christmas period in Italy with also the famous panettone recipe.

In Italy today, Christmas is a time for families coming together and with the recently acquired wealth, this coming together is a great excuse for a boom in buying (expensive) consumer goods especially for children who normally are at the centre of most of the festivities. Italy is very much a religious country and even with growing secularism, Christmas is very much a religious festival, with carol singing, live cribs, and decorated windows in the main stores. This also brings out little quirks in our attitude towards religious feast days.

At Christmas families have awith usually plenty of tacky colourful lights and Santas and angels… not as simple and nice as the Christmas tree of Denmark!. Set up the nativity – usually under the tree – where baby Jesus will be added only on the night of the 24th after attending Mass ! This is, of course, for the true believers… It’s a strong tradional habit to go to Mass on the 24th evening (hoping there will be a coir singing in tune!) Usually we do not eat that much on Christmas Eve (strangely enough…) but we will definitively have some panettone (typical Italian tall cake/brioche full of pieces of dried fruit) with some Prosecco / Italian Champagne.

On the 25th the traditional starting course in Lombardia (region where I come from) is to have “cappelletti in brodo” (small filled tortellini , usually hand made if you have still a grandma that can cook, served in chicken stock). And then, of course, plenty more courses will follow! Presents are opened either on the 24th evening or 25th morning.

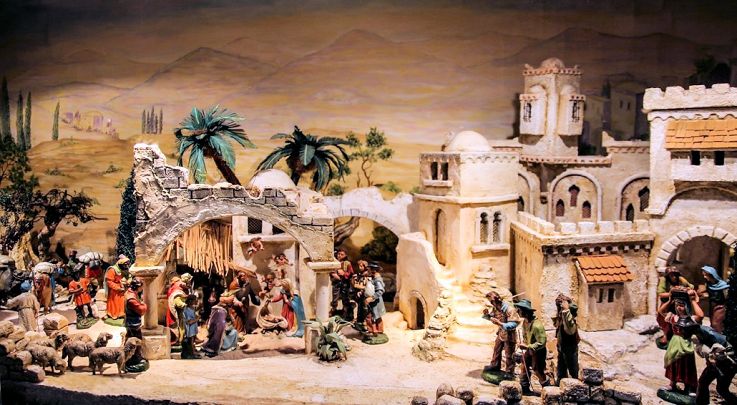

One of the most important ways of celebrating Christmas in Italy is the Nativity crib scene. Using a crib to help tell the Christmas story was made very popular by St. Francis of Assisi in 1223 (Assisi is in mid-Italy). The previous year he had visited Bethlehem and saw where it was thought that Jesus was born. A lot of Italian families have a Nativity crib in their homes. Having cribs in your own home became popular in the 16th century and it’s still popular today (before that only churches and monasteries had cribs). Cribs are traditionally put out on the 8th December. But the figure of the baby Jesus isn’t put into the crib until the evening/night of December 24th! Sometimes the Nativity scene is displayed in the shape of pyramid which can be meters tall! It’s made of several tiers of shelves and is decorated with colored paper, gold covered pinecones and small candles. A small star is often hung inside the top of the pyramid/triangle. The shelves above the manger scene might also contain fruit, candy and presents.

The city of Naples in Italy is world famous for its cribs and crib making. These are known as ‘Presepe Napoletano’ (meaning Neapolitan Cribs). The first crib scene in Naples is thought to go back to 1025 and was in the Church of S. Maria del presepe (Saint Mary of the Crib), this was even before St. Francis of Assisi had made cribs very popular! One special thing about Neapolitan cribs, is that they always have extra ‘every day’ people and objects (such as houses, waterfalls, food, animals and even figures of famous people and politicians!). Naples is also the home to the largest crib scene in the world, which has over 600 objects on it! In Naples there is a still a street of nativity scene makers called the ‘Via San Gregorio Armeno’. In the street you can buy wonderful hand made crib decorations and figures – and of course whole cribs!

One old Italian custom is that children go out Carol singing and playing songs on shepherds pipes, wearing shepherds sandals and hats. On Christmas Eve, it’s common that no meat (and also sometimes no dairy) is eaten. Often a light seafood meal is eaten and then people go to the Midnight Mass service. The types of fish and how they are served vary between different regions in Italy. When people return from Mass, if it’s cold, you might have a slice of Italian Christmas Cake called ‘Panettone’ which is like a dry fruity sponge cake and a cup of hot chocolate! Here’s a recipe for panettone. You can find out more about Christmas in Italy and Italian Christmas Recipes on this site.

For many Italian-American families a big Christmas Eve meal of different fish dishes is now a very popular tradition! It’s known as The Feast of the Seven Fishes (‘Esta dei Sette Pesci’ in Italian). The feast seems to have its root in southern Italy and was bought over to the USA by Italian immigrants in the 1800s. It now seems more popular in American than it is in Italy! Common types of fish eaten in the feast include Baccala (salted Cod), Clams, Calamari, Sardines and Eel.

There are different theories as to why there are seven fish dishes eaten. Some think that seven represents the seven days of creation in the Bible, other say it represents the seven holy sacraments of the Catholic Church. But some families have more than seven dishes! You might have nine (to represent the Christian trinity times three), 13 (to represent Jesus and his 12 disciples) or 11 (for the 11 disciples without Jesus or Judas!)!

The Christmas celebrations start eight days before Christmas with special ‘Novenas’ or a series of prayers and church services. Some families have a ‘Ceppo’ or Yule Log which is burnt through the Christmas season. In Italian Happy/Merry Christmas is ‘Buon Natale’, in Sicilian it’s ‘Bon Natali’ and in Ladin (spoken in some parts of the northern Italian region of South Tyrol) it’s ‘Bon/Bun Nadèl’. Happy/Merry Christmas in lots more languages.

Epiphany is also important in Italy. On Epiphany night, children believe that an old lady called ‘Befana’ brings presents for them. The story about Befana bringing presents is very similar to the story of Babushka. Children put stockings up by the fireplace for Befana to fill. In parts of northern Italy, the Three Kings might bring you present rather than Befana. On Christmas day ‘Babbo Natale’ (Santa Claus) might bring them some small gifts, but the main day for present giving is on Epiphany.

The Italian Panettone

A panettone (literally meaning “big loaf”) is a tall, dome-shaped cake risen with yeast. It has a somewhat light and airy texture but a rich and buttery taste, and it’s not very sweet. It’s a typical Christmas-time cake all around Italy and in Italian communities around the world, but it originates in the northern Italian town of Milan. It traditionally contains raisins and candied fruit (orange and citron zest) and is topped with crisp pearl sugar. More modern versions might substitute the candied fruit with chocolate chips.

Most Italians do not make panettone at home, for the simple reason that it is a rather lengthy and complicated process, requiring multiple risings. Usually, it is bought from a local baker or in a supermarket.

But if you are feeling ambitious and would like to make your own, the following is a rather classic recipe.

What You’ll Need

For the First Rising:

3/8 cup/90 g unsalted butter

5/8 cup/110 g sugar

4/5 cup/200 ml warm water

1/2 teaspoon fine salt

5 ounces/140 g? fresh yeast cake (or? biga; ask your baker for this)

6 egg yolks

3 1/3 cups/400 g flour

For the Second Rising:

2 1/3 cups/280 g flour

1 1/2 teaspoons vanilla extract

6 egg yolks

1 teaspoon honey

5/8 cup/110 g unsalted butter

1/2 pound/200 g raisins

1/2 cup/100 g granulated sugar

1/2 teaspoon fine salt

A little flour, for dusting the work surface and

Optional: pan? pearl sugar (for decoration)

Optional: 1 cup candied orange and/or lemon peel, diced

How to Make It

The afternoon before you plan to bake the panettone, begin by cutting the butter into a small pot and melting it over a very low flame or a double boiler; keep it warm enough to remain melted. Dissolve the sugar in about 2/5 cup (100 ml) of warm water.

Put the melted butter, salt, and yeast cake in a mixing bowl (or better yet, the bowl of an electric mixer) and mix well. Next, add the yolks and sugar-water, mixing briskly. Sift in the flour, continuing to mix. If the dough is too stiff, add a little more water. Continue to mix briskly for about 25 minutes, throwing the dough against the sides of the bowl, until it has become smooth, velvety, and full of air bubbles. At this point, transfer the dough to a lightly floured bowl large enough for it to triple in volume, cover it with a heavy cloth, and keep it in a warm (85 F, 30 C) place for about 10 hours.

Wash the raisins, drain them well, and set them on a cloth to dry.

When the first rising time is up, turn the dough out onto your work surface (or return it to the mixing bowl) and work in the flour, vanilla, yolks, and honey. Mix briskly for about a half hour, then work in all but 2 tablespoons of the butter, which you will have melted as before, and a little water (just enough to make an elastic dough), to which you have added a pinch of salt. Continue working the dough until it becomes shiny and dry, and at this point add the fruit and zest, working the dough to distribute it evenly. At this point you can divide the dough into pieces of the size you want; if you want to make your panettone by weight, use a scale and figure that they’ll decrease in weight by 10% during baking.

Lightly grease your hands with the butter and round the balls of dough, then put them on a board or plate and let them rise in a warm place for about a half hour. At this point, lightly butter your hands again and put the panettoni in panettone molds (or put rings of stiff paper around their bases). Return them to their board and put them in a warm (68-80 F, 20-30 C, depending upon the season), humid spot to rise for about 6 hours.

Heat your oven to 380 F (190 C). Cut an x into the top of each panettone and put 2 tablespoons (30 g) unsalted butter over the cuts. Put the panettoni in the oven, and after 4 minutes remove them and quickly push down on the corners produced by the cuts. Return them to the oven and bake them until a skewer inserted into the middle comes out dry about 1 hour.

When chefs remove their panettoni from the oven, they put them upside down in special panettone holders to keep their flanks from collapsing. In a home situation, this is not practical, and you’ll simply have to cool your panettoni on a rack.

Some tips: Work the dough, if possible, with a standing dough mixer of the kind also used for making bread dough. Beating times with a mixer are on the order of 20 minutes, whereas hand-beating will require about 50.

The room where the panettone is made must be warm, about 72 degrees F (22 C). The flour should also be warm, about 68 F (20 C); what’s used is 00 grade (very fine all-purpose flour) and extremely dry. If it has been wet where you are, you may want to dry your flour in an oven, as it absorbs moisture unless it is tightly sealed. The water used should be warm, about 76 F (24 C).

Don’t forget a pinch of salt, because it stimulates rising.

Commercial bakers use a sourdough starter (i.e., wild yeast). Home recipes call for baker’s yeast.

The baking time will depend on the size of the panettone. Assuming an oven temperature of 400 F (200 C), half an hour will be sufficient for small to medium-sized panettoni, whereas larger ones will require considerably more. Home ovens are best suited to small-medium-sized panettoni.

If you want the surface of the panettone to be shiny, slip a bowl of water into the oven when the panettone is half-baked to raise the humidity.

Commercially sold panettoni are taller than they are broad. To obtain this effect at home, you’ll have to put a ring of heavily buttered thick paper around the dough when you put it in the oven or use a panettone mold . If you instead want a panettone that’s wider than it is high, like a normal bread loaf, simply put the dough in the oven. If you choose this course, you will want to put the dough on a pizza stone or similar.

Read also our other posts on Christmas;

Read also our other posts on Christmas;

Christmas markets in England ;

Christmas markets in Italy and Germany ;

Christmas tree origin and quotes ;